The idea of the IMMA Collection #WakeupwithArt posts on our social channels is to ease you into your day with some of our observations or passing thoughts around aspects of the IMMA Collection that connect certain works thematically, that sometimes may be topical or current in everyday life and that you may find of interest.

Each week we explore a theme and draw your attention to 7 works, one per day, with links to those works and artists for more information. With some of the artists involved the theme may concern a deep and enduring area of interest while for others it may just be a motif or nuance.

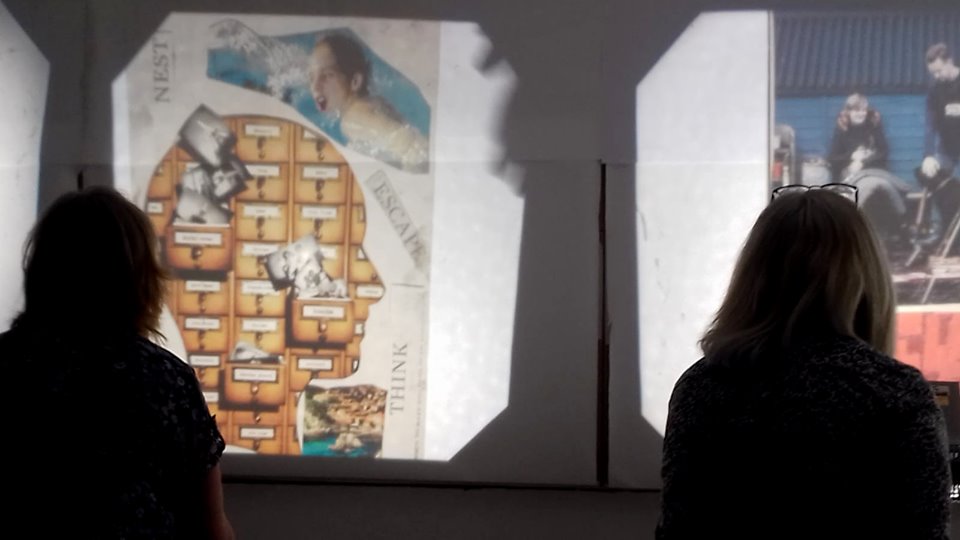

This week our daily #IMMACollection posts explored the theme ‘Our Place in Space’. Our Head of Collections, Christina Kennedy, selected 7 works, one a day, here she introduces the theme and explores the works that connect with it.

………………………………………………………………………

I’m sure we’ve all noticed how bright the stars and how limpid the night skies appear in recent times since the ban on industry and personal travel around the globe. One upside of the COVID-19 crisis is to learn how quickly our earth is positively responding to being left alone, borne out by scientists on the International Space Station who report how much clearer the earth’s atmosphere is looking.

While we are all in Lockdown, advancing scientific knowledge and testing of new technologies continue above us in the outer reaches of the earth’s atmosphere.

Recently broadcaster and space expert Leo Enright, invited us to look out for the International space station and Elon Musk’s 60 Starlink satellites SpaceX, (like a string of pearls), as all traversed the skies 400km above Ireland. Unfortunately dense cloud cover that evening, at least over Dublin, put paid to catching a glimpse.

Since time immemorial, the vastness of the earth’s night skies have been a reminder of our human scale and the limits of our looking. We’ve watched the stars to help us find our way, to mark seasonal change, inspire spiritual contemplation, provoke scientific enquiry and influence the production of great works of art and architecture.

Our Neolithic ancestors combined all of these in their production of one of the greatest monuments of the pre-historic world, Ireland’s 5400 year old New Grange passage tomb, a place of astrological, spiritual and ceremonial importance, famously aligned so that the rays of the winter solstice sunrise shine deep into its chamber.

Fast forwarding to the last millennium: from Albrecht Durer’s woodcut celebrating the renowned 10th century Persian astronomer, Al Sufi, to Andy Warhol’s Moonwalk Portfolio commemorating the first man on the moon, artists have been fascinated by our place in the cosmos.

The past 25 years in particular have seen a real burgeoning of artworks that magnify the connections between aesthetics, science and astronomy. Science fiction in particular holds a lot of fascination for certain artists, in terms of space exploration and new ecologies, ideas about extra-terrestrial life, simulacra, parallel universes, virtual worlds and much more.

Here are the IMMA Collection works we’ve shared this week:

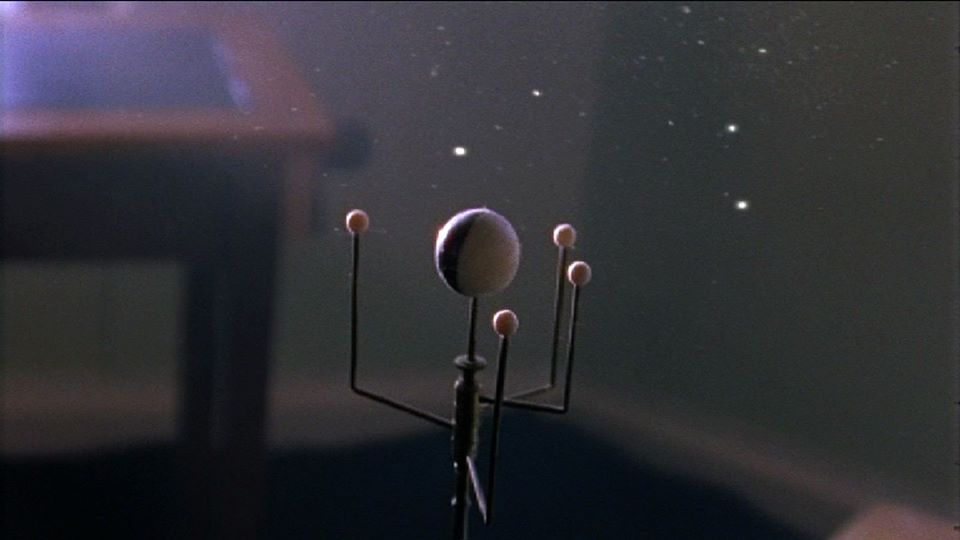

Sultry Moon (2008) by Janaina Tschäpe

This limited edition print was created on the occasion of Tschäpe’s solo exhibition Chimera at IMMA in 2008. Like many of her paintings, films and photographic works it embodies a sense of the extraordinary, where the everyday world becomes a magical if sometimes melancholy place.

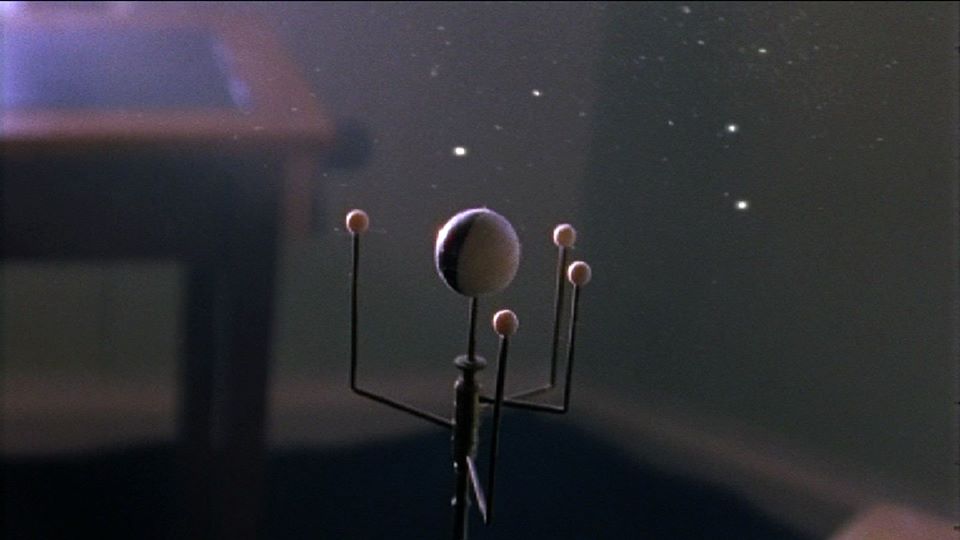

Dust Defying Gravity (2003) by Grace Weir

Grace Weir’s films, photographs, installations, drawings and performances reflect on discoveries in astro-physics as well as ruminating on the history of discovery itself and the lives of pioneering individuals. Her film Dust Defying Gravity is set in the observatory at Dunsink where panning shots trace the atmosphere and air, the particles of dust, which stream and swirl, echoing the stellar activity as seen through the Observatory’s telescope.

Other works by Weir have focused on conversations with astrophysicists, explorations of the spatial theories of Einstein, 3D simulations of clouds and the study of black holes. Her films propose ideas that telescope into the distant past and future and materialise in some way the time-feel of space.

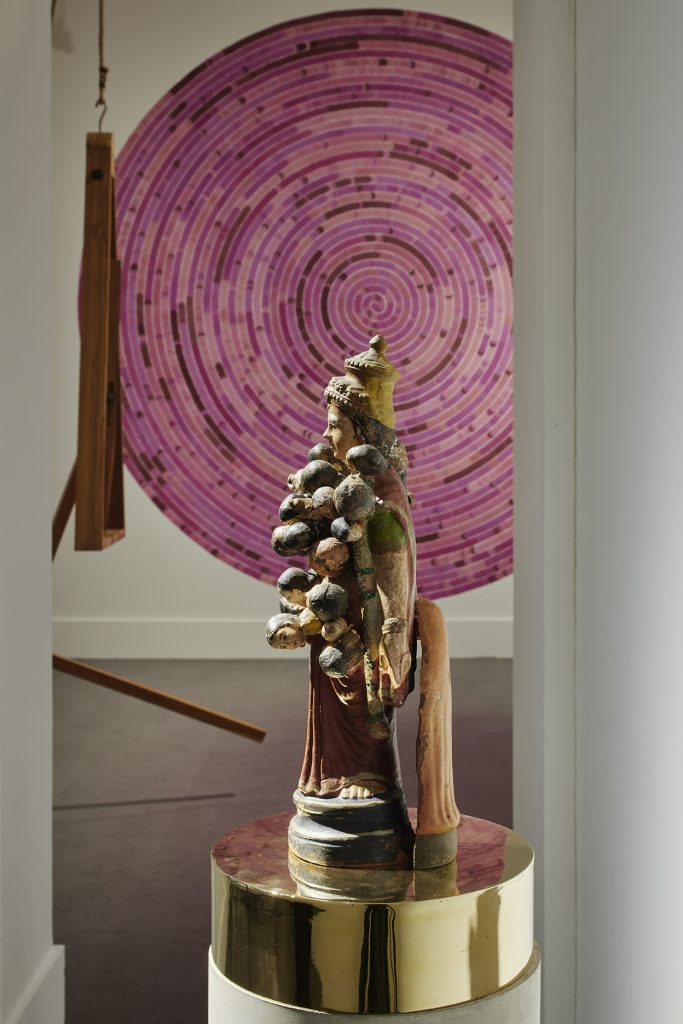

The Weakening Eye of Day (2014) by Isabel Nolan

This spiral-shaped, sculptural work, of steel wadding, wool and thread, provided the title of Isabel Nolan’s solo exhibition at IMMA in 2014, in which the artist tasked herself with compressing the past, present and future of the universe into just four intimately scaled rooms.

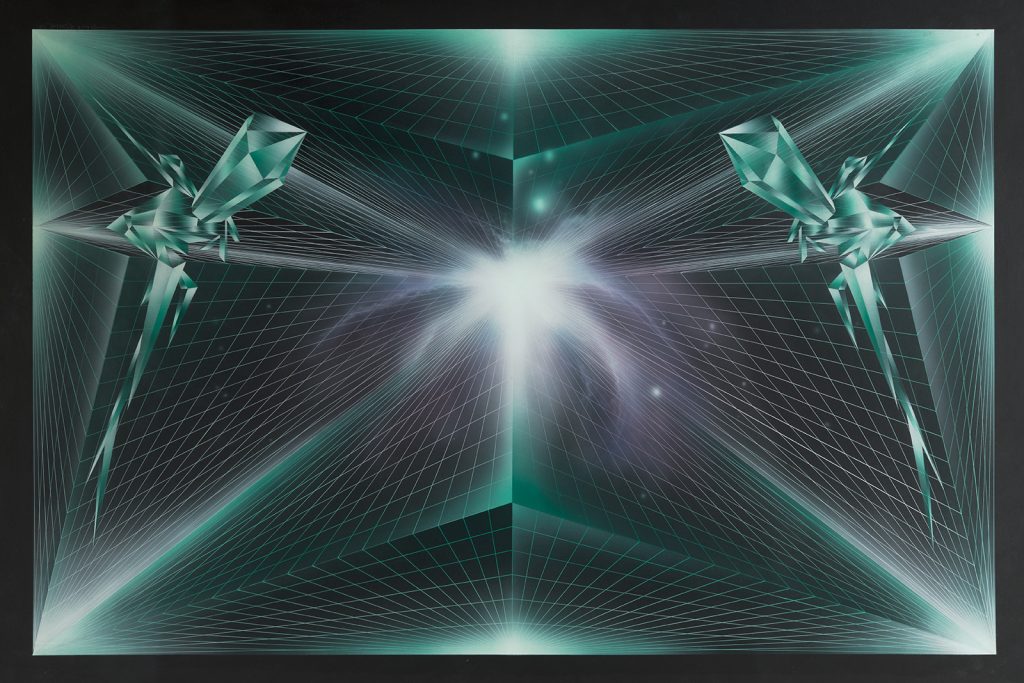

The Navigator (1982) by Michael Mulcahy

The solitary navigator in this painting by Michael Mulcahy expresses a deep restlessness which has led the artist to travel extensively and seek a world where man and nature are more closely entwined. A period spent with the Dogon people of Mali led to a series of intense paintings incorporating symbolic forms based on their understanding of the constellations, and the religious beliefs associated with them. These paintings give the sense of a world coming alive at night and man’s connection to the cosmos giving meaning to our existence.

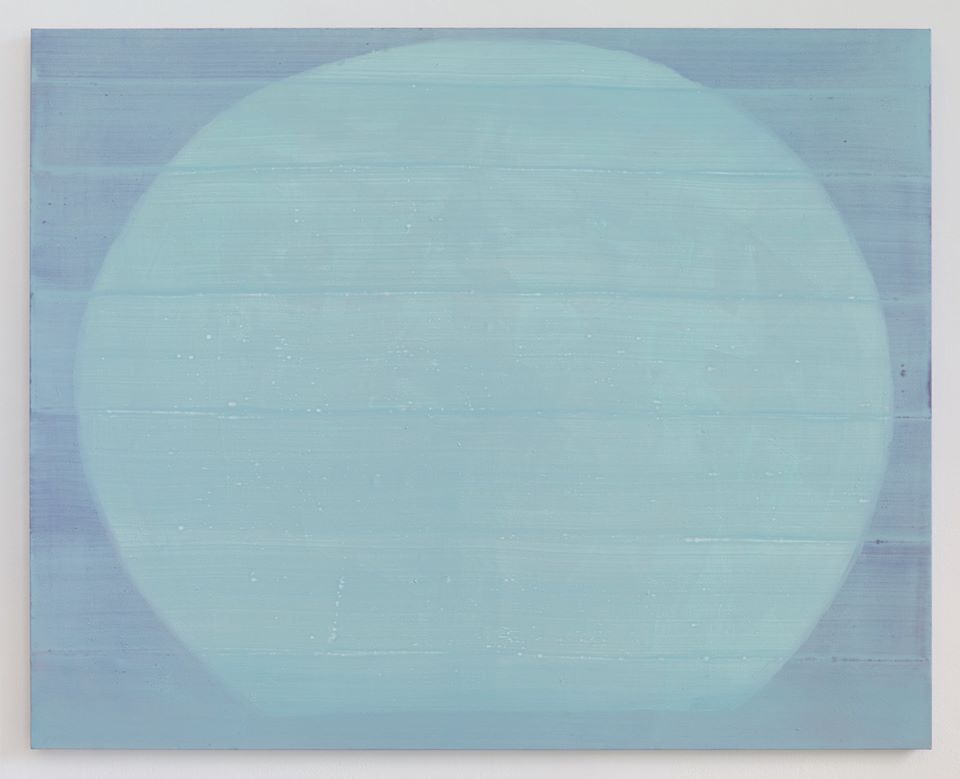

Boy From Mars (2003) by Philippe Parreno

This film by Algerian/French artist Philippe Parreno is a chain of dream-like images of mountains, stars, clouds and water buffalo and is a paean to nature. While the title references Mars, this is a science fiction pastoral, an ode to light and extra terestrial visitation. There is no Martian boy but an orange glow subtlely alludes to the Red Planet and radiates a warm orange light which flickers and intensifies bringing certain elements to the fore especially as dusk becomes night.

Hybrid Muscle, the title of the eco-designed shelter featured in the film, suggests an otherworldly pavilion both primordial and surreal, like a UFO, which has landed in an unknown tropical landscape. It is a hybrid of a science fiction film-set and an eco-designed shelter with flapping plastic walls which work in the same way as temporary shelters made of teak leaves. The slow ambulations of an albino water buffalo, harnessed to a pulley system for an hour a day, provide all the building’s power needs.

ADDENDUM:

The Hubble Space Telescope and the tale of Tim Robinson’s ‘Washer’

In 2020 the Hubble Space Telescope achieves its 30th year in orbit. Hubble has fundamentally changed our understanding of the cosmos. It has brought the universe home to Earth on social media, with new images, videos, documents etc. However, it’s earliest endeavor after its launch into space 30 years ago met with a problem. Its first communications once in orbit and sending astronomical images back to earth, revealed its lense to be fractionally out of sync and therefore out of focus. This turned out to be due to the omission of a tiny washer when the telescope was being built. It was subsequently successfully repaired in a highly delicate procedure by astronauts in space.

In one of his remarkable essays “Backwards and Digressive” (2015), Tim Robinson revisits his early artworks and reconsiders his thought processes and philosophy and how these latterly revealed themselves to him as the foundations for his later explorations as a writer and map-maker.

One such object was ‘Washer’ 1972, a small circular disc which Robinson spotted on one his walks across London in the early ‘70’s. The act of writing the essay helped him “to work out what role this little disc plays in my own explorations of time and space..”:

“.. Gleaming on the pavement before me was a washer mislaid by someone servicing a motorbike or a car. I began to collect these ‘points’ as I came to term them, trying to commit to memory whatever vague ramblings my mind had reported in that moment of recall, so that by the time I had brought them home they already represented a bygone instant, a ‘now’ foregone.

“..In my imaginary gallery of points pride of place goes to the washer lost in the building of the Hubble telescope. It stands for the first of all moments, separating not past from future but nothing from something; it is the grain from which the Universe burst into existence and begat all that is and ever will be. All things stand at ground zero of that explosion; it links us all in a universal cousinage. It is the All-Thing lying in the palm of the mystic, bereft perhaps of maker and sustainer, but not of love.”