On 28 June 1969 police raided The Stonewall Inn, a gay bar in Greenwich village New York, the 200 patrons resisted against the discriminatory police raid and rioted. A year later a committee was formed to commemorate the riots – Gay Pride was born.

This year parades and parties have been cancelled so we look at new ways to celebrate and commemorate. This week, Chris Jones, our Visitor Engagement Team supervisor turns a queer eye on the IMMA Collection and explores works by LGBTQI+ artists.

……………………………………………………………………..

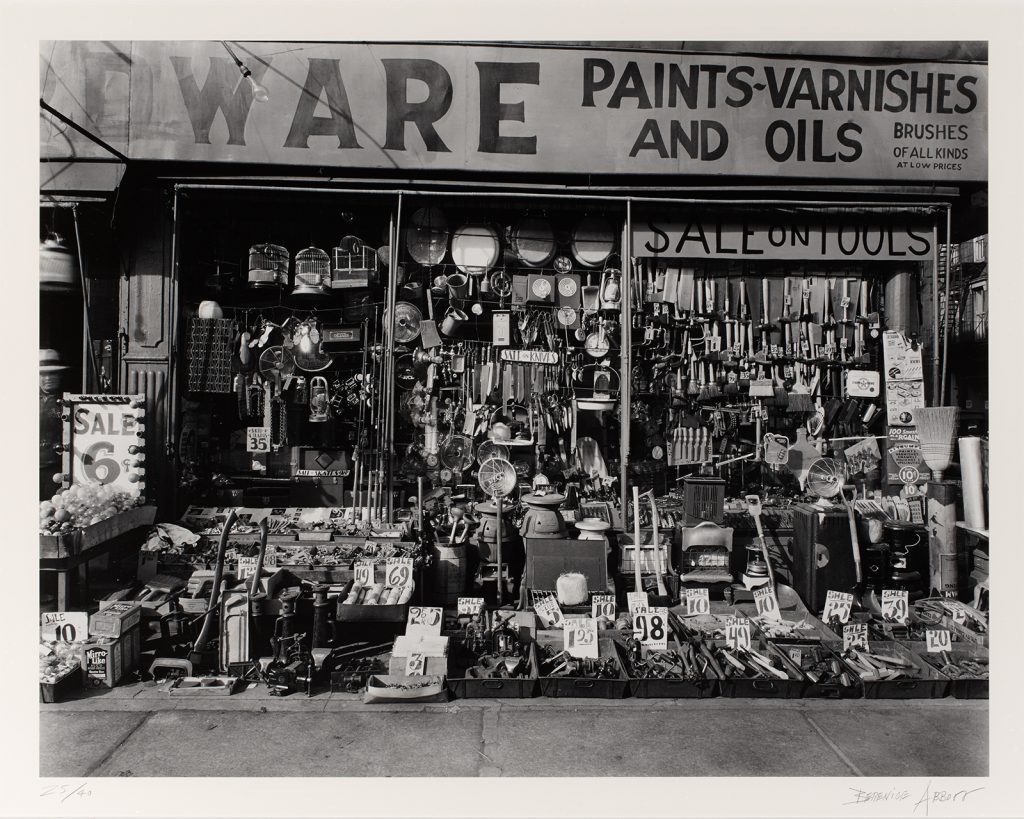

Lets return to New York where it all began with Berenice Abbott‘s Hardware Store, 316-318 Bowery, Manhattan, 1938.

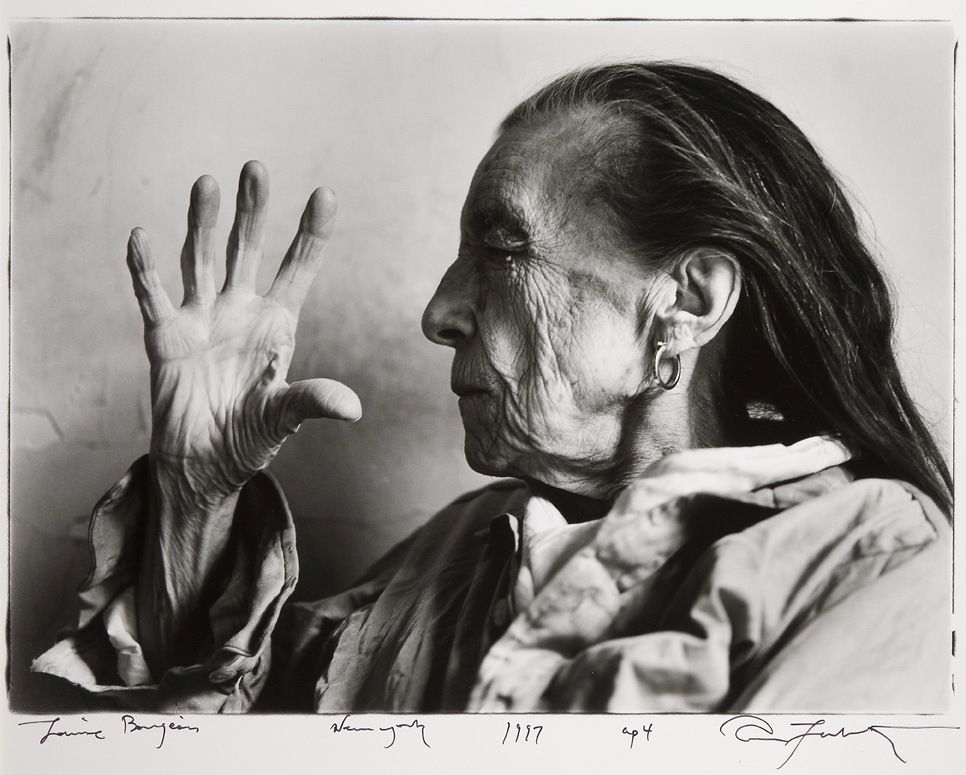

Born in Ohio in 1898, Berenice Abbott would become one of America’s greatest photographers, after rejecting a career in journalism, Abbott moved to Paris in 1921 where she discovered her love for photography working as a darkroom assistant for Man Ray. She opened her own studio specialising in women’s portraiture, mostly lesbian expats, although James Joyce famously sat for her and she took the now iconic portrait of Eileen Gray in 1926. Returning to New York from 1935 to 1939 Abbott began working on the documentary project Changing New York which would become her most defining body of work. Around that time she met her partner, art critic Elizabeth McCausland. Changing New York contains 307 black and white prints of a rapidly evolving city and it’s people.

Hardware store is part of that series – taken in the Bowery, a less than savoury neighbourhood at the time, Abbott famously said after being warned against venturing there on her own : “Buddy , I’m not a nice girl, I’m a photographer…I go anywhere”. Berenice and Elizabeth would move into 30 commerce street Manhattan where they would remain together until Elizabeth’s death in 1965. Hardware Store, 316-318 Bowery, Manhattan was part of the exhibition Picturing New York in 2009.

Further reading:

NYC LGBT historic sites project

https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/stonewall-inn-christopher-park/

https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/berenice-abbott-elizabeth-mccausland-residence-studio/

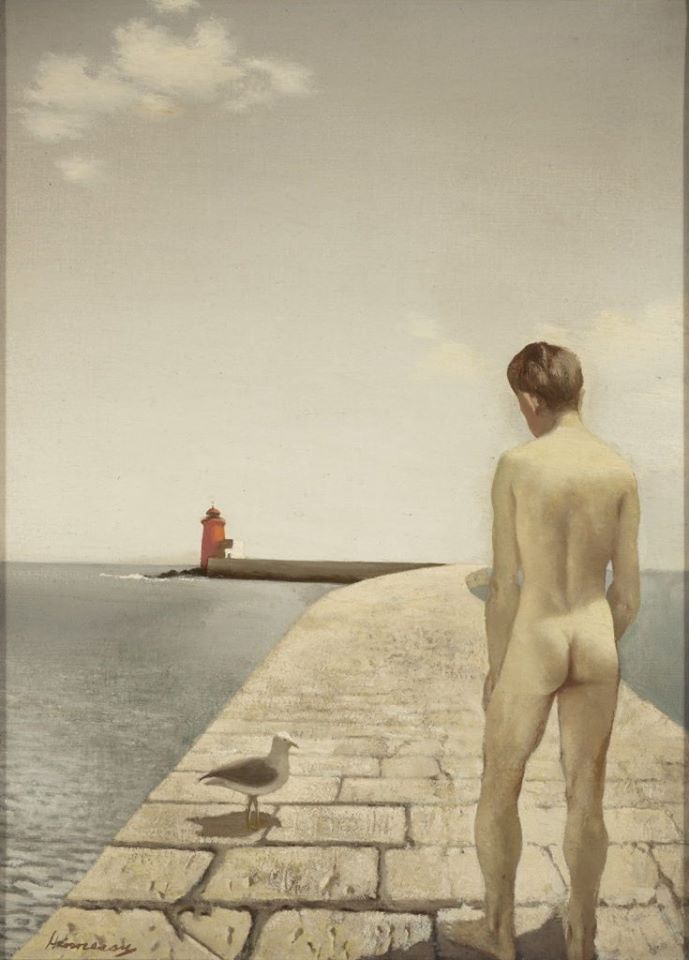

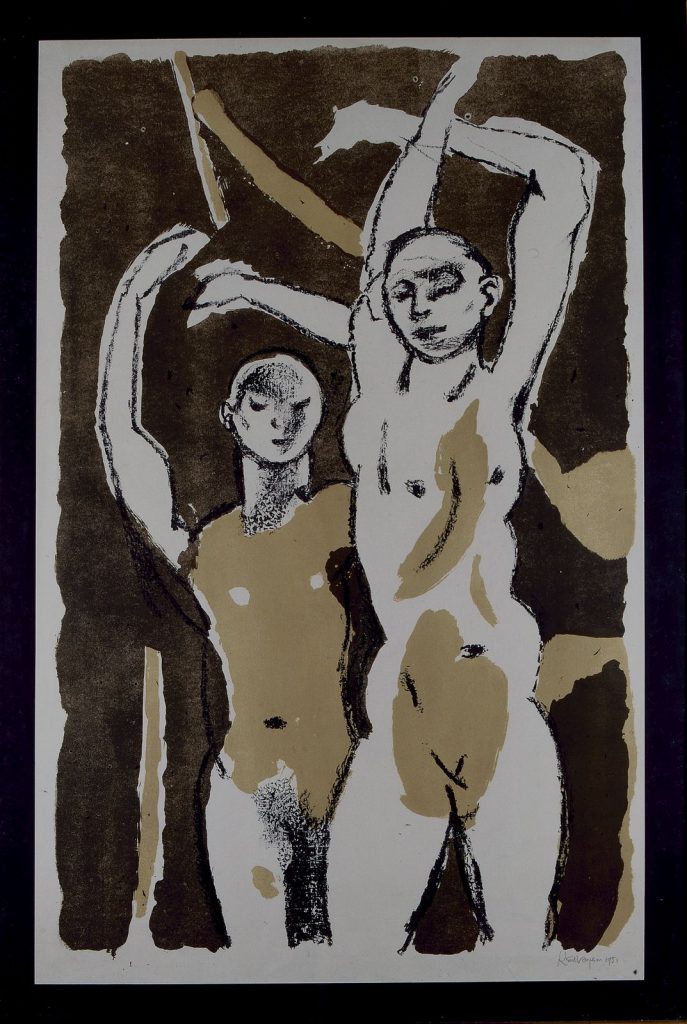

Festival Dancers (1951) by Keith Vaughan

An important figure in post war British Art, Keith Vaughan was a self taught painter,he became involved in the Neo romantic movement while living with fellow artists Graham Sutherland and John Minton but eventually leaving it to focus more on the male nude and abstraction.He also went on to teach in Camberwell College of Arts, the Central School of Art, and the Slade School in London. Living a largely closeted life he wrote extensively about his struggle with his sexuality and depression in his journals which were published after his death in 1989. England in the 1950’s was a difficult time for queer artists, when Francis Bacon’s Two figures in the grass was shown at the ICA in 1955 members of the public called the police to report Bacon for obscenity.

By using greek and classical references in his work, Vaughan’s male nudes often escaped such accusations – however thinly veiled. He was not a fan of Bacon’s work – one entry in his journal describes Bacon’s portraits of Lucian Freud as “a new low in banality”. He was however, since his teenage years an avid fan of Ballet and attended performances as often as he could. Festival Dancers 1951 shows how his interest in ballet informed the work :Two young men, arms stretched upwards in the 5th position pose, waiting to begin, together but never touching. Vaughan was 55 when homosexuality was decriminalized in 1967.

Further reading/viewing:

Keith Vaughan: Under the Skin

Uncover the thoughts and processes of painter Keith Vaughan

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/keith-vaughan-2096/keith-vaughan-under-skin

The personal papers of Keith Vaughan:

https://www.tate.org.uk/art/archive/tga-200817/personal-papers-of-keith-vaughan

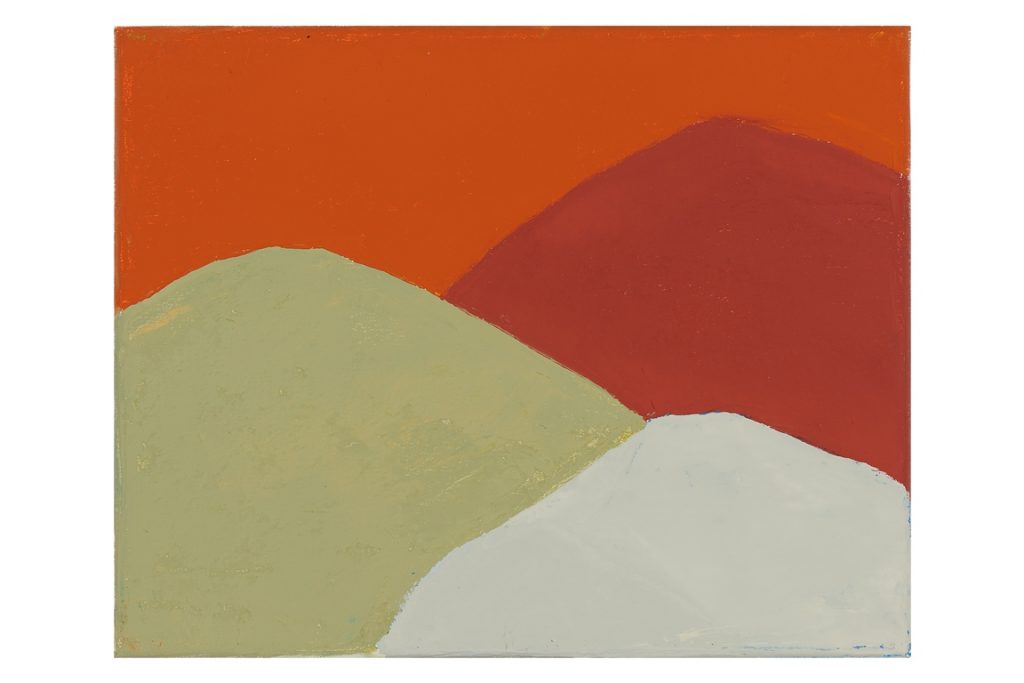

Untitled (213) (2013) by Etel Adnan

We walked many nights through

beds of flowers

telling each other

the mountains move secretly stars

betray their order

rivers and flowers

are women in love

excerpted from “The Spring Flowers” by Etel Adnan

Lebanese american artist and poet, Etel Adan’s works spans a multitude of genres, languages and geographies. Born in Beirut in 1925, she studied at the Sorbonne in Paris, U.C. Berkeley, and Harvard in the US. Initially writing in French, which she then rejected as a sign of solidarity for the Algerian war of independence. She joined the poets movement against the Vietnam war,where she became in her own words “an American poet”. After her mother died in 1958 she settled in small town north of San Francisco, it is here where she began to paint, inspired by this place between the sea and the mountains.

In 1972 she met Syrian sculptor Simone Fatal in Beirut, the couple would move to California and Paris where they now reside nearly 5 decades later. In California she would fall in love with the terrain of Mount Tamalpais which she would return to in countless variations throughout her life. Blocks of shape and vibrant colour which she lays with a palette knife, these abstractions have a spiritual quality rooted in the vast landscapes of the Lebanon and her adopted home of Marin county.

Further reading/ viewing/ listening

Rachel Thomas, Senior curator : Head of exhibitions, IMMA in conversation with Etel Adnan. Rachael Gilbourne, Assistant Curator: Exhibitions, introduces the exhibition Etel Adnan at IMMA 2015 here.

Composer Gavin Bryars sets eight of Adnan’s “Love Poems” collection to music: Adnan Songbook I.

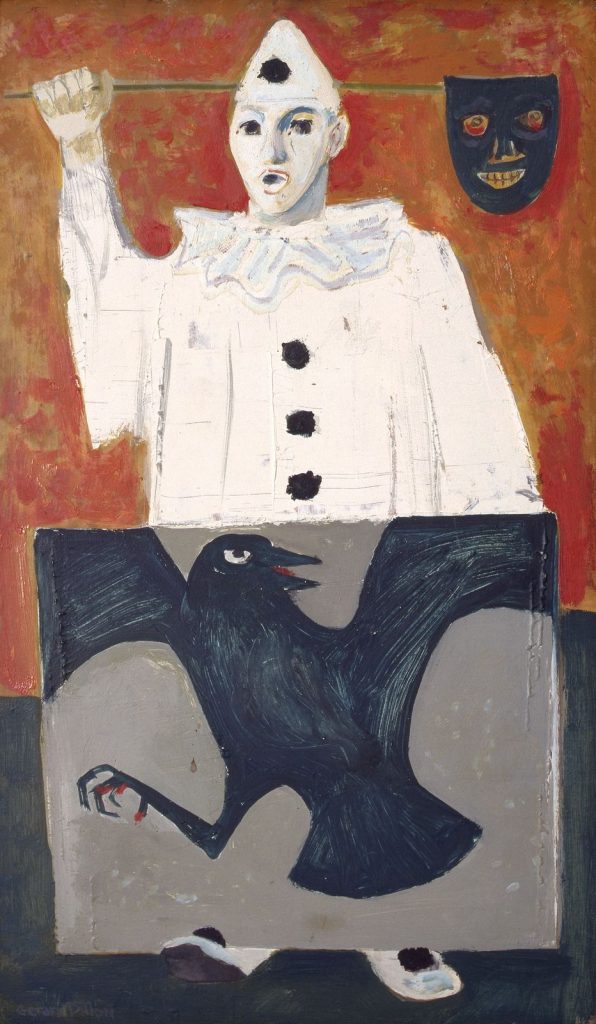

Clown with bird canvas (1960) by Gerard Dillon

Gerard Dillon was born into a Catholic family on the Falls road Belfast in 1916, brought up by a staunchly Catholic mother and British army veteran father. He was shy teen, struggling with feelings of guilt and that Homosexuality was a “mortal sin” – he turned to the church for support confessing his desires for young men to his priest only to be told that he would burn in hell for such “unnatural” feelings and was angrily threatened with excommunication. Feeling trapped and abandoned he left Belfast on his 18th birthday to join his siblings,working alongside his older brother Joe who was also gay, something that they were reluctant to discuss with each other.

Working as a house painter he discovered his love of paint and colour, with his savings he bought oils and canvas and traveled to the west of Ireland in 1939 where he was struck by its rugged beauty which would strongly influence his early work. During the war years, He moved to Dublin where he fell in with the art scene.Here he met Mainie Jellett who helped him get his first solo show in The County Shop in St Stephens Green. His relationships were short and furtive and would often spend time cruising for men in the Dublin docklands, Dillon never had a long term close relationship in his lifetime. The influence of his sexuality has often been ignored in his paintings. Pierrot would appear frequently in his later work, the sad clown with only the moon for a friend.

In Clown with a bird canvas we see the alter ego of the artist carrying a grinning mask over his shoulder, open mouthed as if startled at being found unmasked. An ominous crow at his feet, its claws bloodied. Dillon never explained his work he believed that it should speak for its self. When asked about clowns in his work he said ,”They all come from the side of me that’s over there”. From 1943 he was a regular contributor and committee member of the Irish Exhibition of Living Art. He represented Ireland at the Guggenheim International in 1960 and the Marzotto International Rome in 1963. Dillon lived in Dublin from 1968 until his death.

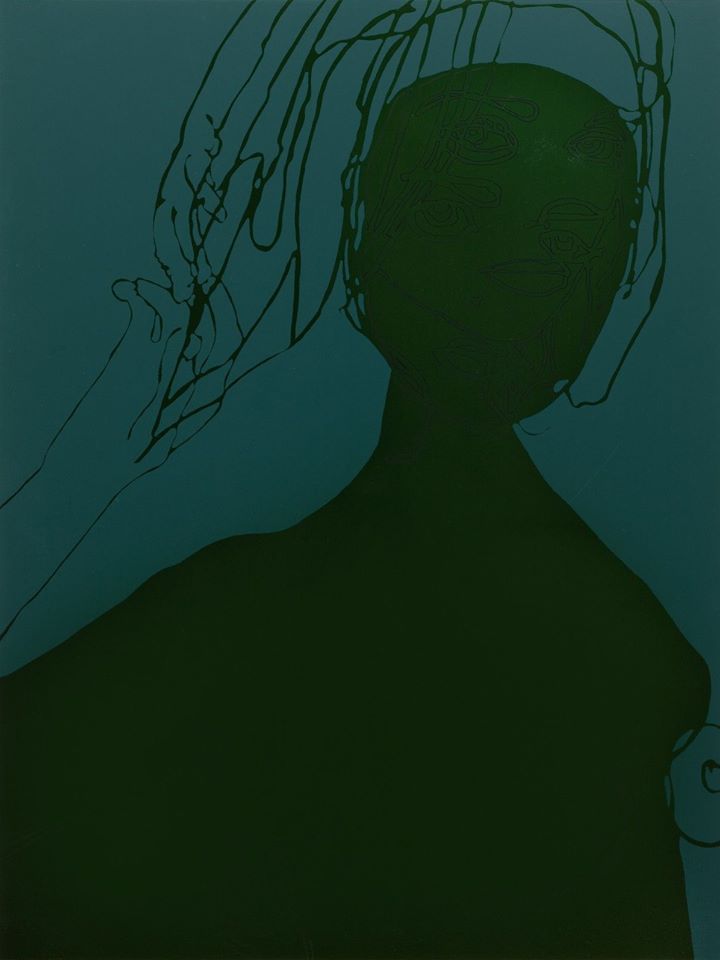

Small small talk book (1953) by Sonja Sekula

Sonja Sekula’s role in one of the seminal art movements of the 20th century has largely been forgotten the world of abstract expressionism compared to her male counterparts such as Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko and Robert Motherwell. The contributions of many women artists of the movement have generally been under-acknowledged if not completely overlooked. Born in Lucerne Switzerland, Sekula moved to new York with her parents in 1936 at the age of 18. She enrolled in The Sarah Lawrence College where she studied Philosophy, literature and painting.Following a trip to Europe with her parents, she suffered a mental breakdown which was the beginning of her life long battle with mental illness.

Sekula began enjoying success at age 25 with a series of exhibitions, including solo shows at Peggy Guggenheim’s Art of the Century Gallery and at the Betty Parsons Gallery, Reviews in both America and Europe were favorable and enthusiastic. She was an out lesbian at a time when it was practically unheard of to be.At various clinics she was subjected to conversion therapy, shock therapy, and other inhumane treatments as lesbianism was seen as a “debilitating manifestation of schizophrenia”.It was likely that she had Bi Polar disorder or schizophrenia which today would be treated with medication.

In the early 1950s and 1960s, Sekula blended haiku poems with biomorphic shapes in the form of sketch books. In Small small talk book, over washes of purples and blues she sketches a loose female form and write in pencil : “…Make a choice…love is pain intensified + to freeze without it is pain intensified. “Puzzle: “ which one of the two?”. Sonja Sukula took her own life at the age of 45. She is now regarded in her native Switzerland as one of the most important artists of the twentieth century, although her work still is not widely known elsewhere.

Further reading:

The painter Sekula, her life and work : https://www.sonja-sekula.org/

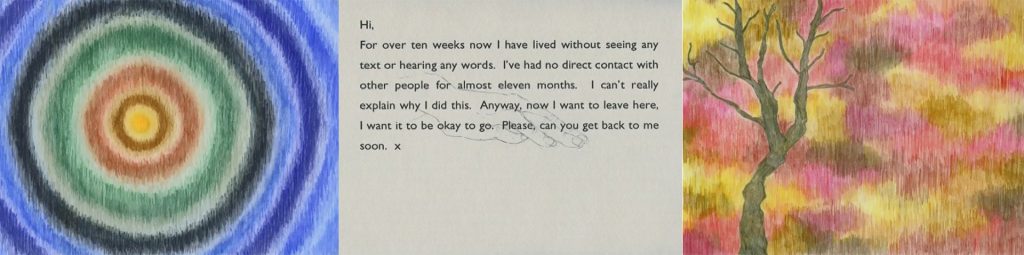

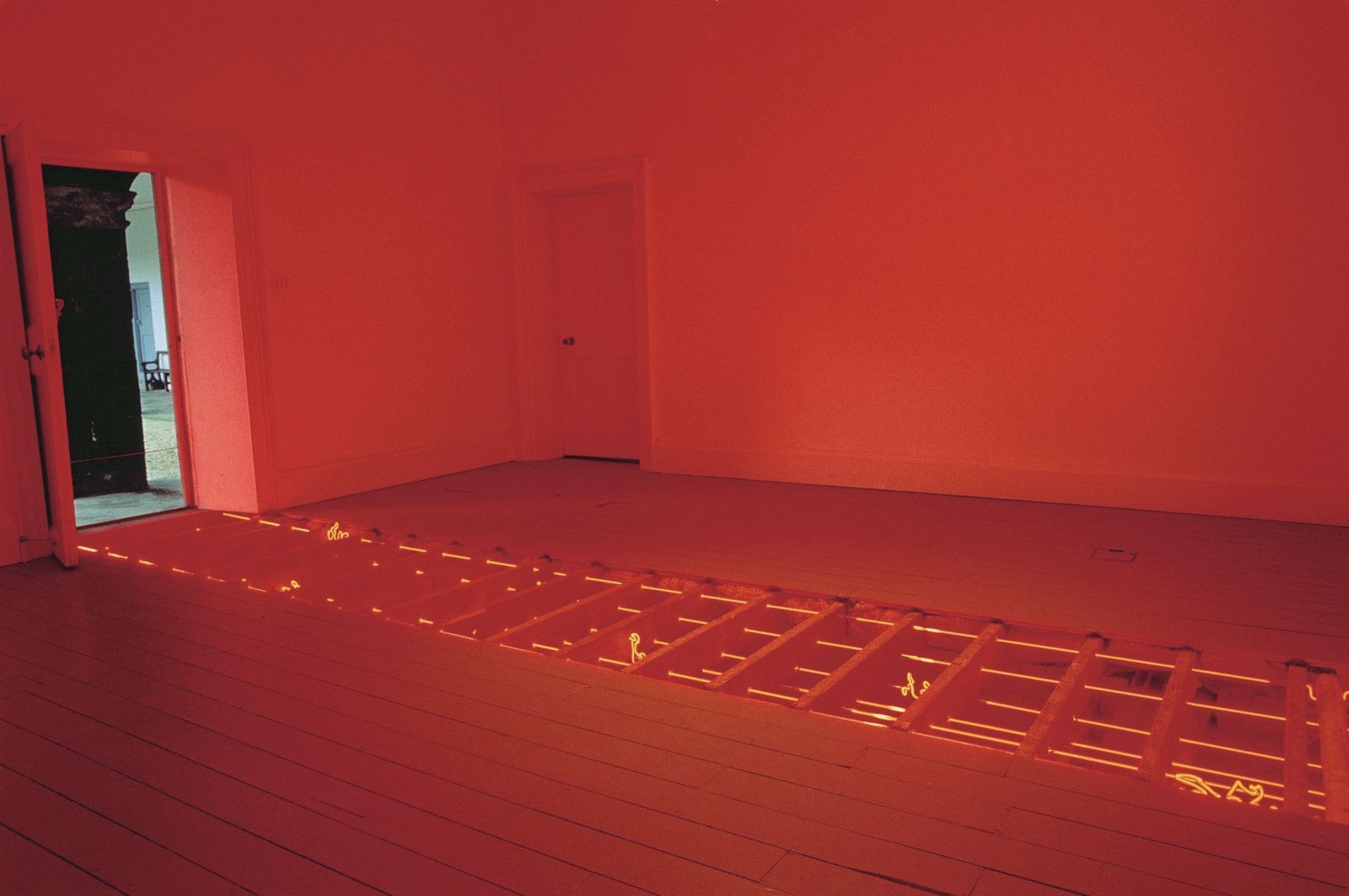

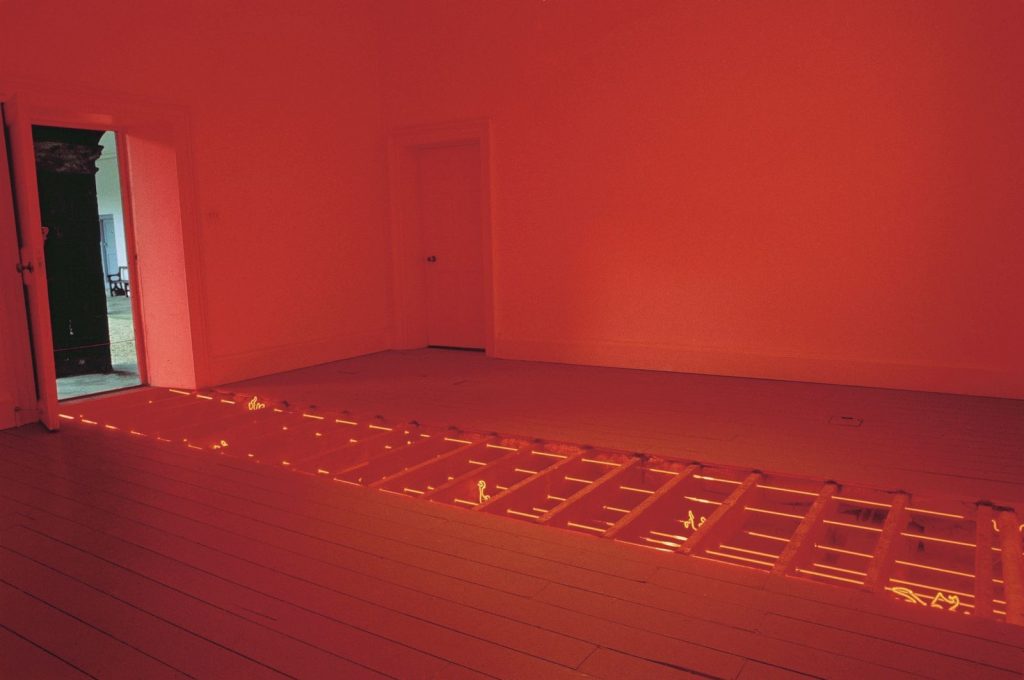

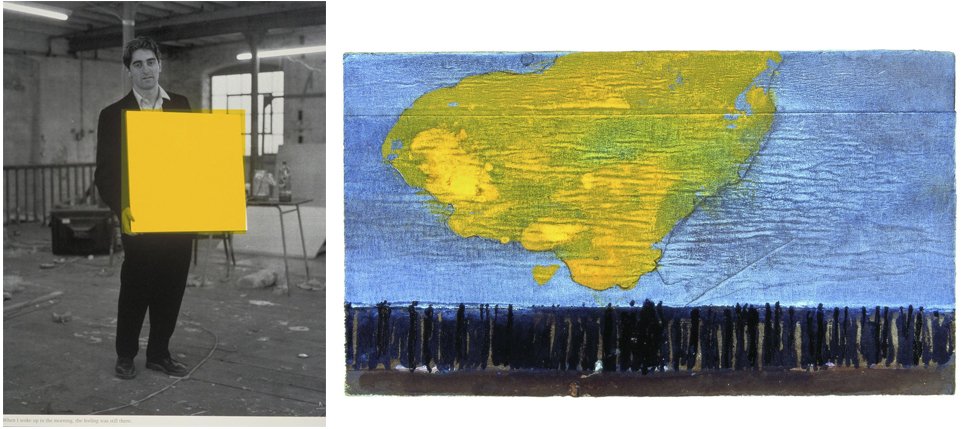

Everything Disappears (2014) by Kevin Gaffney

Kevin Gaffney is an artist filmmaker from Dublin, he graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2011 with an MA Photography and Moving Image, and was awarded the first Sky Academy Arts Scholarship for an Irish artist in 2015. He was an UNESCO – Aschberg laureate artist in residence at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art’s Changdong Residency in South Korea (2014) and received the Kooshk Artist Residency Award to create a new film in Iran (2015). A monograph of his work, Unseen By My Open Eyes, was published in 2017. He is currently a PhD researcher at Ulster University. Gaffney’s work examines themes of LGBTQ identity, homophobia, stereotypes, gay conversion therapy and queer history. While on residency in Taipei, Taiwan in 2014 he developed Everything Disappears, a film which explores ideas of self-image, performance and identity. Working with four local people who answered a open call, he filmed each participant in their home creating an intimate portrait in 7 chapters.

The fourth chapter, The Elephant on the Roof is inspired by an email Gaffney received from a young gay man who described his stay in a psychiatric hospital in order to escape military conscription and the need to perform his illness in order for it to be observed by the doctors and the subsequent weakening grip on reality that he experienced. The resulting film is a surreal journey, often Lynchian in it’s imagery and soundscapes, Everything disappears is a sensitive portrait of relationships and identity.

Further reading:

Upcoming Exhibition, https://crawfordartgallery.ie/expulsion-kevin-gaffney/

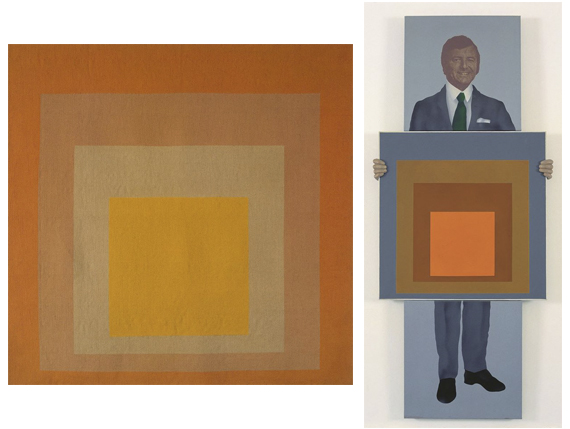

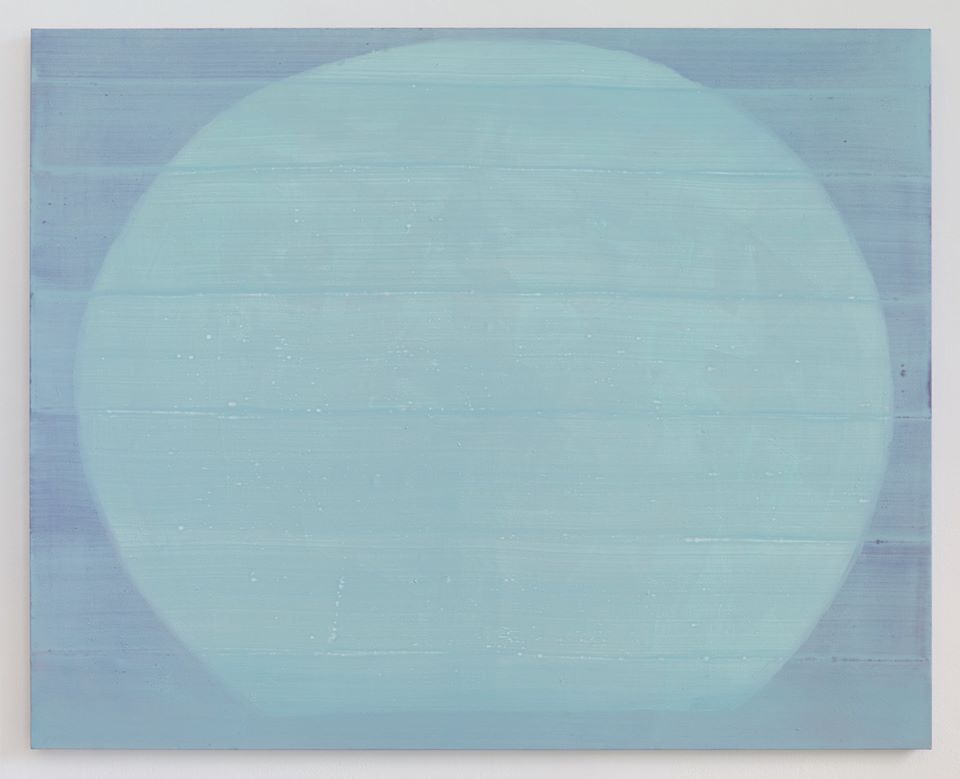

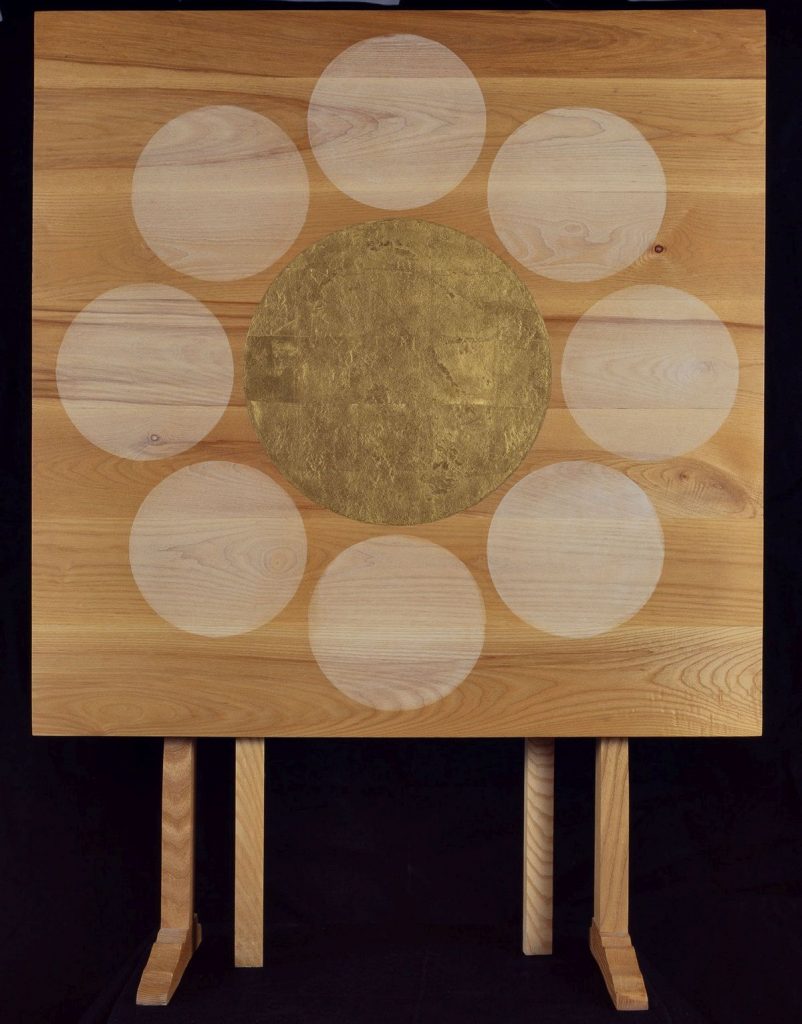

Meditation Table IX (1991) by Patrick Scott

On The last day of a week of exploring LGBTQI+ artists in the IMMA collection, the final queer eye focuses on Patrick Scott,a giant in Irish Modernism.

Many solemn nights

Blond moon, we stand and marvel

Sleeping our noons away

Teitoku, Japanese Haiku

Born in west Cork in 1921,He studied architecture at University College Dublin and worked for 15 years for the architectural practice of Michael Scott, he was involved design of Busáras in Dublin where his beautiful mosaics can still be seen.He Represented Ireland in the Venice biennale in 1960 and also won the Guggenheim Award the same year, it wasn’t until then that he took up painting full time. While in his 20’s Scott met theatre actor Pat McLarnon, they moved into a house in Baggot lane where they became known affectionally as the “two Pats” by their neighbours. They would remain there until McLarnon’s death in 1998. While openly gay he always remained private about his relationship with McLarnon and would refer to him as “a great friend”.

His early work explored the natural word such as birds, trees and the Irish boglands. Later he began to become more interested in abstraction and geometric shapes, particularly, the circle which is a recurring motif in his work. Inspired by eastern philosophy and his visits to China and Japan, he is most well know for his gold paintings made in the mid 60’s, combing gold leaf and tempura on raw canvas. His later works such as Meditation Table IX also show his interest in Zen Buddhism. In the center of the table a large circular mandala is painted in Gold leaf surrounded by smaller white ones in tempura, the Mandala, a symbol of spiritual totality and wholeness in life. At the age of 92 Scott celebrated civil partnership with his partner of 37 years, Eric Pearse. He died a year later on Valentines day 2014 on the eve of the opening of a retrospective of his work, Patrick Scott: Image, Space, Light at IMMA.

“We got dressed and went down and got married. We had some lemon drizzle cake and champagne with some friends. It wasn’t a large party. Pat is 92 now – large parties aren’t his thing.” (Eric Pearse on their wedding day).

Further reading/Viewing:

Read Christina Kennedy, Senior curator, Head of Collections at IMMA Magazine article on Patrick Scott: Image Space Light exhibition here.

Watch Golden Boy documentary here.