IMMA’s Head of Collections, Christina Kennedy, introduces us to The Artist’s Mother, a project created in responses to the IMMA Collection: Freud Project. Inspired by Lucian Freud’s paintings of his mother, Lucie, the project presents the work of artist Chantal Joffe who has portrayed her mother, Daryll, in a series of paintings and pastels. In this article Kennedy explores both Freud and Joffe’s artistic processes as they provide certain insights into the intense bond between mother-subject and artist-child, and the difficulty of seeing the real woman with adult eyes.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

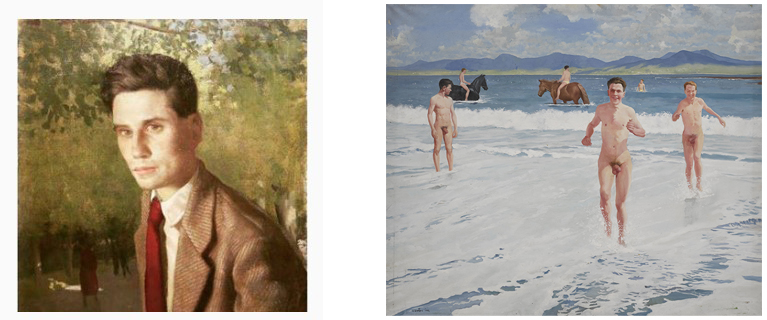

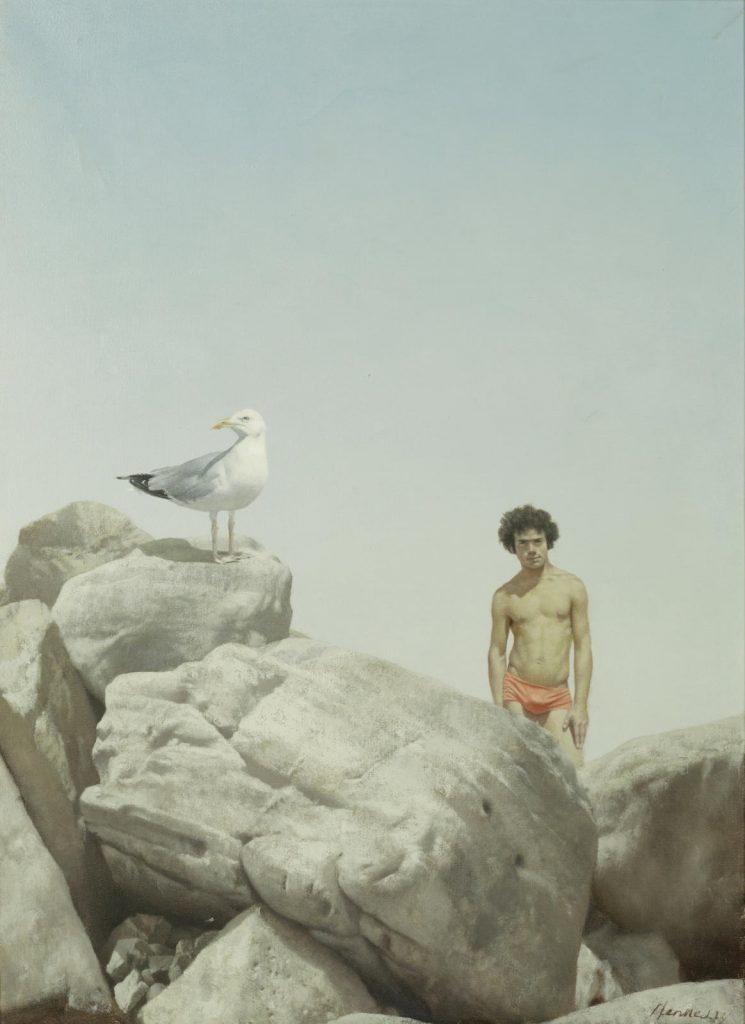

Artists have portrayed their mothers throughout history. We think of Durer’s or Rembrandt’s searching, tender portrayals of the physical signs of aging, more than 500 years ago, to the more recent psychological, empathetic images of Alice Neel or Celia Paul. Among the most arresting mother paintings in 20th century art are those by Lucian Freud, The Painter’s Mother Reading, 1975 and The Painter’s Mother Resting I, 1976, which feature in the 52 works by Lucian Freud on long term exhibition at IMMA as part of the Freud Project (2016-2021).

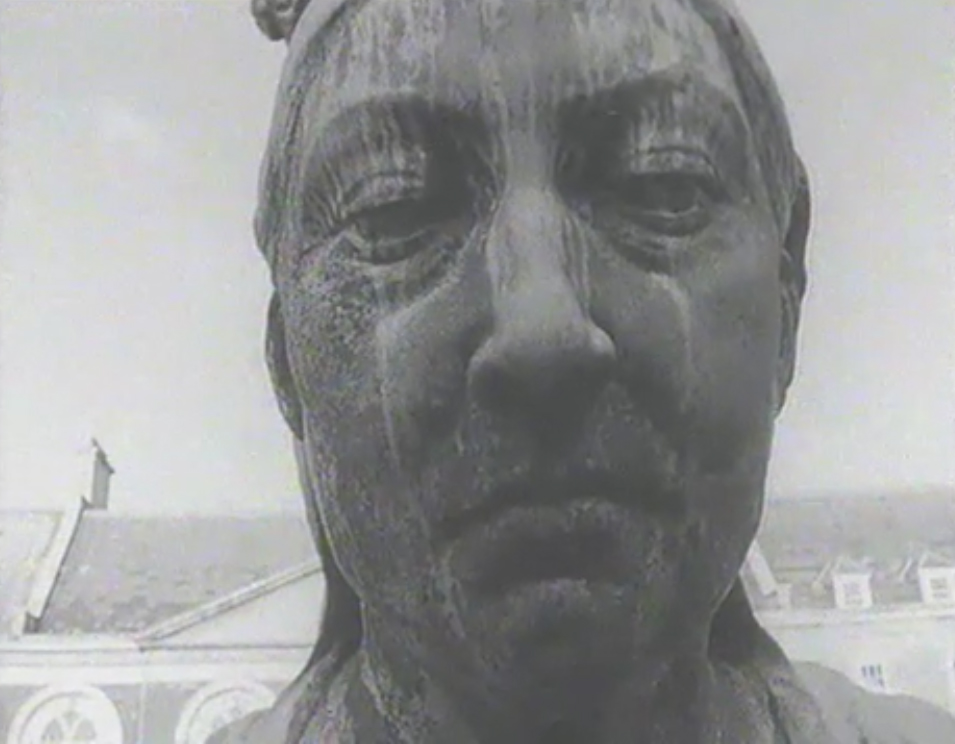

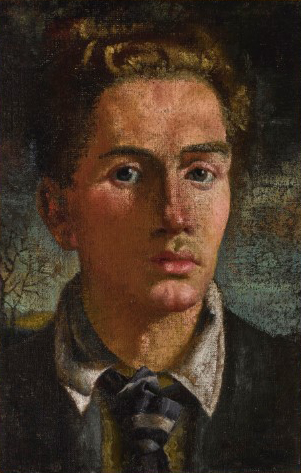

Freud made 13 paintings of his mother Lucie Freud (1896-1989) as well as numerous drawings and sketches, almost entirely during the 10 years before Lucie’s death at the age of 93 (apart from childhood and adolescent drawings). Lucie Freud (nee Brasch) was an indomitable woman who left Berlin in 1933 ahead of the rise of Nazism to make a new life in England with her family.

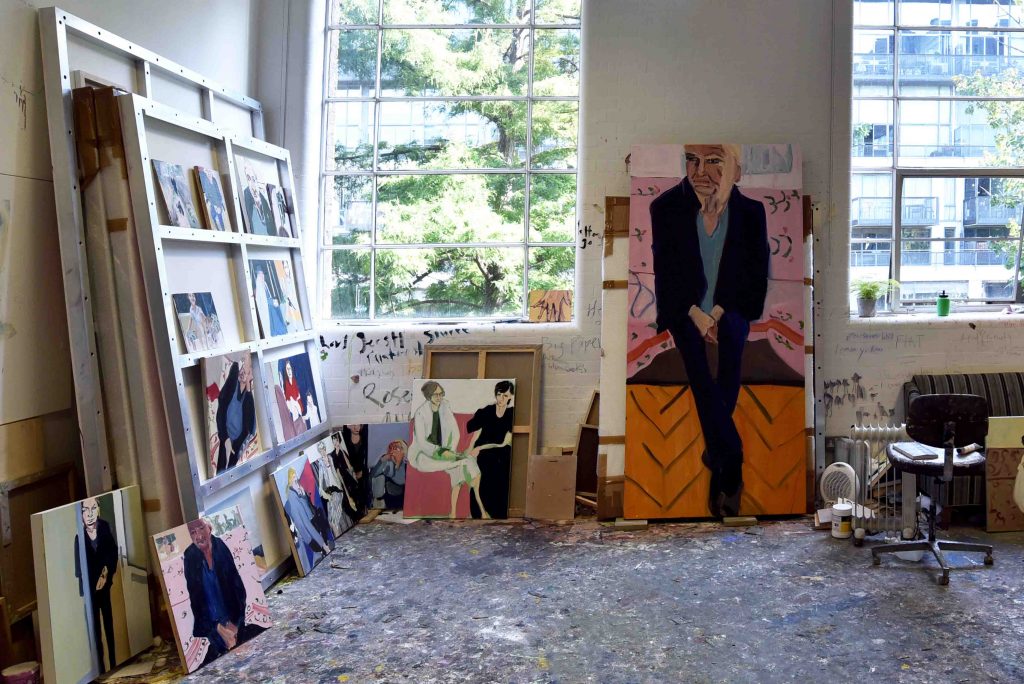

We invited artist Chantal Joffe in 2019 to begin a dialogue with Lucian Freud’s portraits of his mother as part of our ongoing programme in the context of the Freud Project. The Artist’s Mother: Lucie and Daryll is the resulting exhibition. Originally scheduled for September 2020, Covid-19 intervened and so we have re-orientated our exhibition to the current online presentation.

Both artists’ works are in conversation, in a ‘double-portrait’ of sorts that combines a digitally installed exhibition of 15 of Joffe’s works in a virtual gallery space alongside Freud’s portraits of his mother, as well as a focussed display of six pastels and etchings by Joffe in the physical gallery space and that may be seen with the 52 works by Freud when IMMA re-opens.

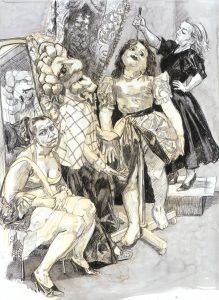

Through paintings, drawings, videos, essays, poetry and programmed talks The Artist’s Mother provides a compendium of images and voices that explore the role of mothers and carers and the bonds of creativity and intellect. It provides a locus for contemporary discussions of motherhood, focusing particularly on the complex relationship between mother and child over time. Both Freud and Joffe’s artistic processes provide certain insights into the intense bond between mother-subject and artist-child and especially the difficulty of seeing the real woman with adult eyes.

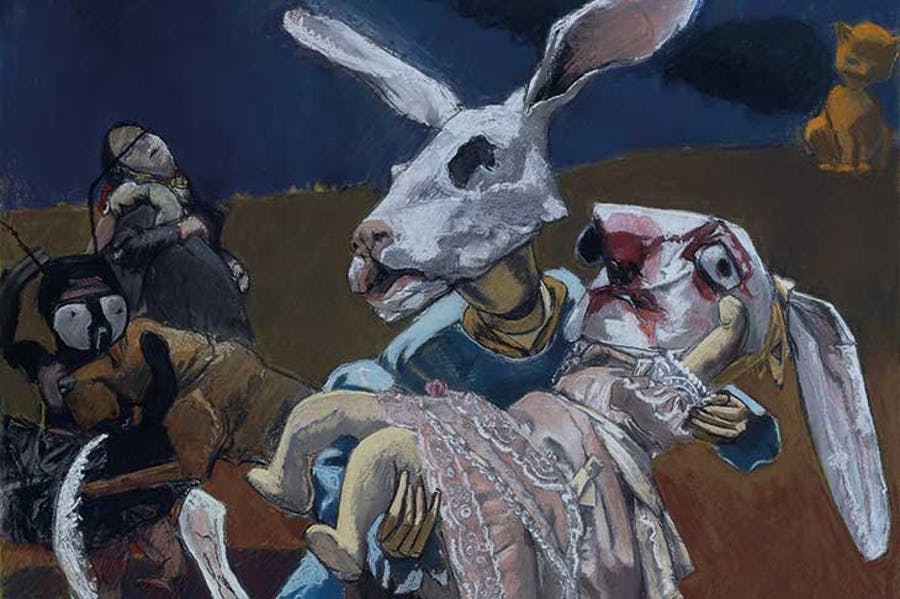

Chantal Joffe has long focused on portraiture. She has depicted her mother Daryll in an exceptional series of paintings and pastels over time, a selection of which are in this exhibition as well as a number of new works as a result of looking at Freud. Joffe’s mother Daryll Joffe, was an exile who arrived in London aged 23. There she worked as a childcare officer and had her first child Emily. Moving to the US following her husband’s teaching job at Stanford University and later Vermont, Daryll’s other children Natasha, Chantal and Jasper were born in the US. The family then returned to London 1983 where Daryll and her children all now live.

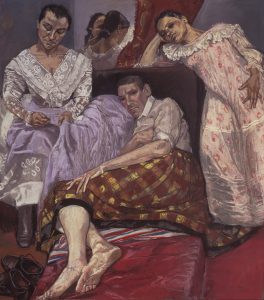

Always very secretive, in his youth Lucian Freud resisted his mother’s attention and her unerring instinct for knowing what he was doing or thinking. After Lucie’s husband Ernst died in 1970 she had tried to commit suicide, was rescued but there were side-effects and she no longer engaged with life. Freud felt he could be with her because she had lost interest in him and therefore he could paint her. He would collect her from her home and bring her to breakfast before starting the day’s sittings. Three mornings a week she would climb the stairs to his studio on the top floor.

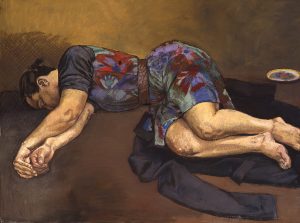

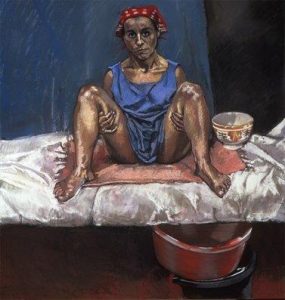

Freud’s working process was forensic, slow, and required hundreds of hours of his sitter’s time to take the artist to their inner world so that he might convey the sitter’s complex psychological relationship with the world. Freud found ‘the harder you concentrate, the more things that are really in your head start coming out…’ The Painter’s Mother Resting I, is one of a remarkable series of three paintings in which Lucie is resting on the bed wearing the same paisley-patterned dress. Freud stated he had difficulty with the pattern. It’s as though the paisleys are a sort of stress point, that something else is happening here, some contingency that catches the figurative content by default.

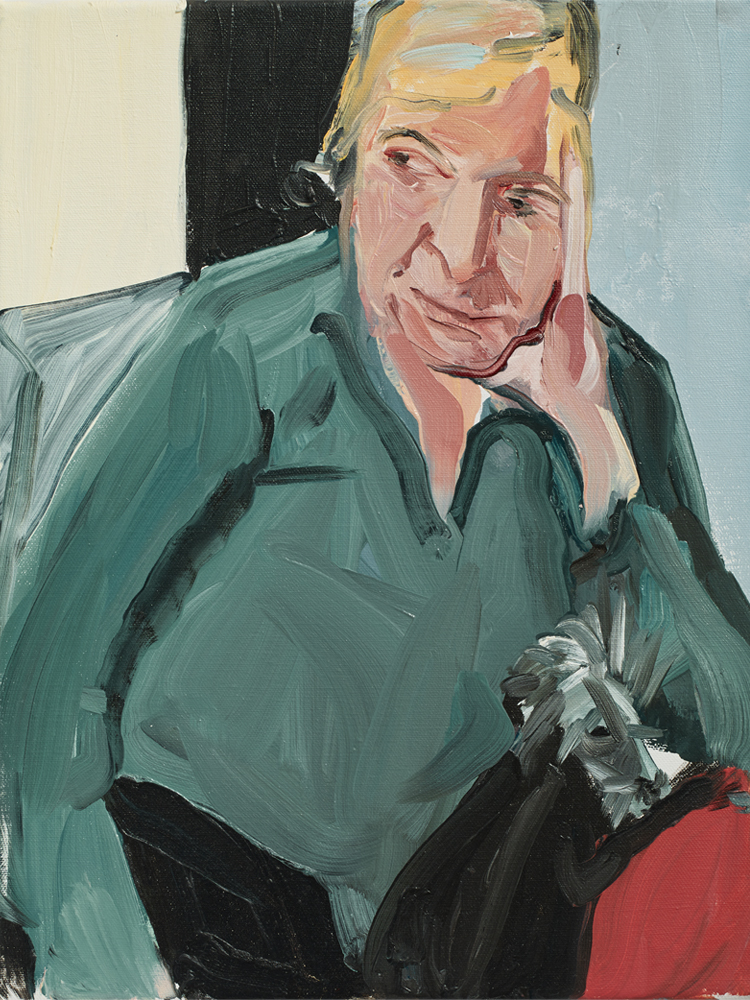

Chantal Joffe likewise returned to painting her mother when in old age, after she began to lose her sight.

“My mum has quite bad sight now – which is a hard thing to say because it became easier to paint her because she couldn’t then see the paintings. It’s complicated,” she says, “she is only truly seen when she can no longer see me or how I paint her” – Chantal Joffe

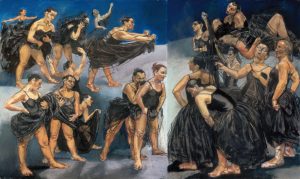

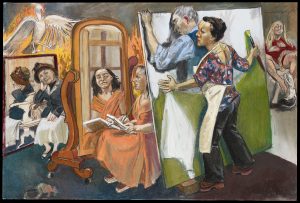

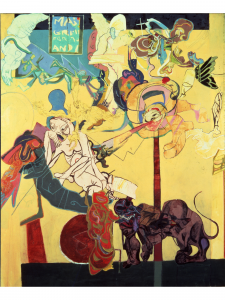

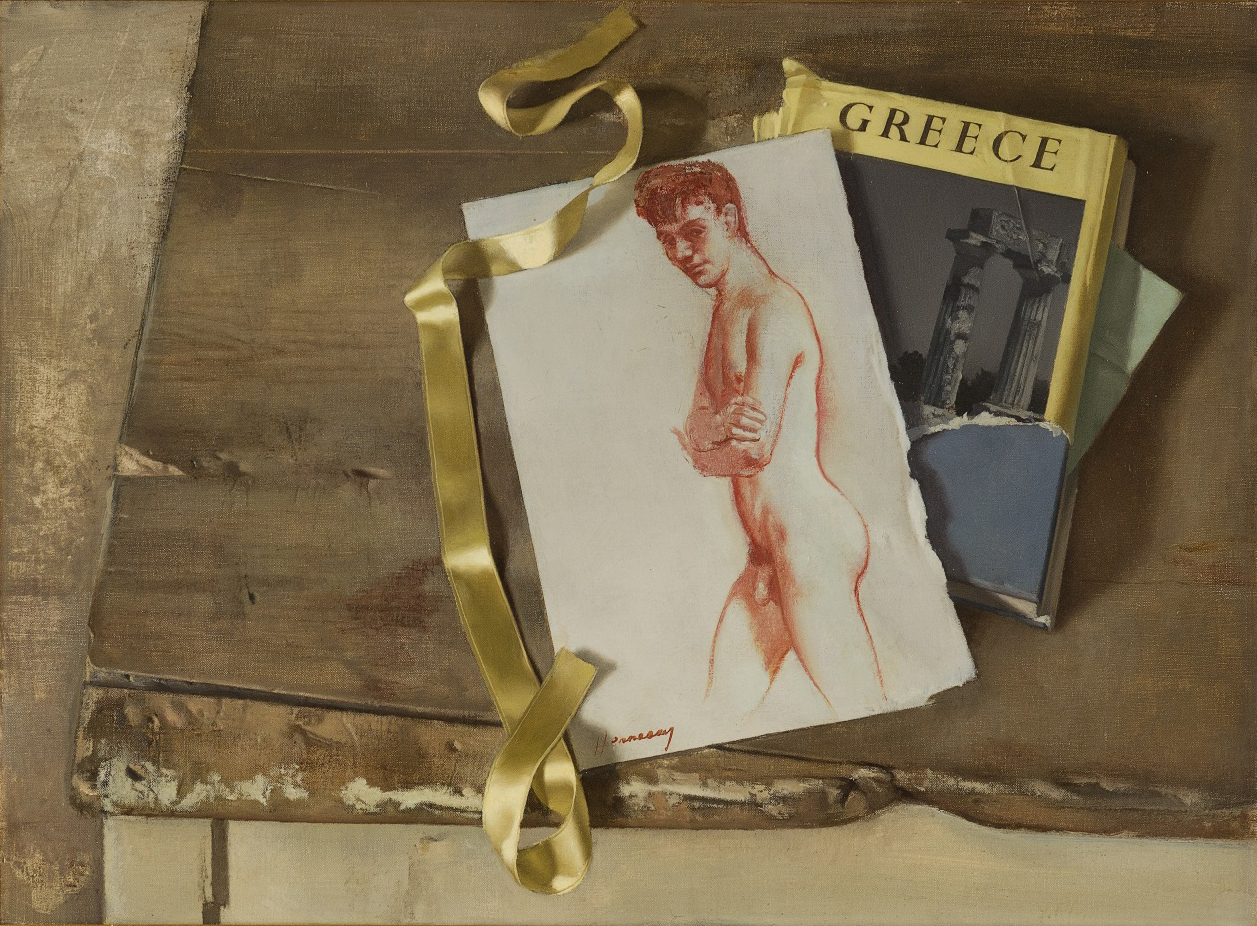

Works such as My Mother at the Door, 2020 lay down line, form and colour in a visceral process that conveys the immediacy of the encounter and mood and a palpable sense of personal feeling and experience of one’s mother. While double portraits such as Conversation, 2016 and Self Portrait in a Striped Shirt with my Mother II, 2019 catch the humour of everyday situations and exchanges. As with Edward Hopper’s windows, motifs of windows and doors are used in Joffe’s works as framing devices that keep the viewer right there looking, reading the space, relationships and everyday experience.

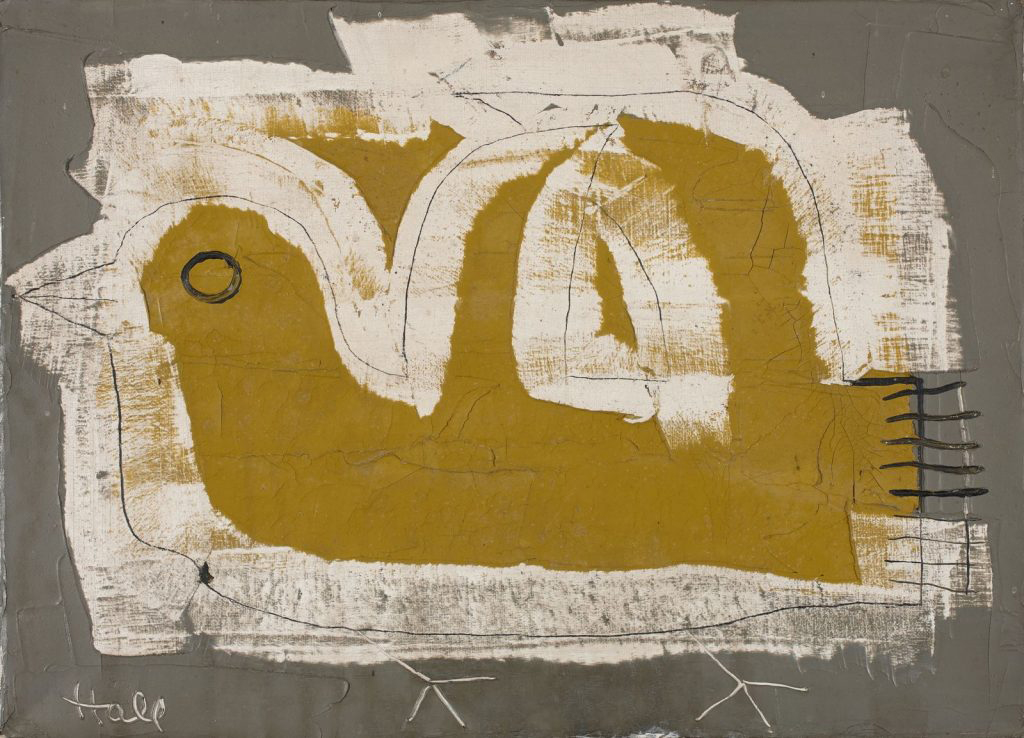

Joffe starts over time with a slow and continuous process of reading, looking and watching. This is followed by gestures in paint or pastel which are fluid and immediate. The movement and rapidity of her process pick up on the incidental and the accidental, on emotions of memory and of the moment. In works such as Sanibel 1994 and My Mother with St Leonard with the Dogs, 2015 you sense the artist’s hand, the sentience of repetition and memory of movement no longer requiring the mind to engage. Form becomes an emotional heartland, “the curve of an emotion” in James Joyce’s words, born, perhaps, of rhythms that effect us from childhood: nursery rhymes, prayers, games.

The encounter between Freud and Joffe’s work is elaborated through Joffe’s conversations with poet and artist Annie Freud, Lucian’s eldest daughter. Annie Freud recites her poem Hiddensee (2019) which reflects on the impact on her grandmother Lucie, as a mother of a young family who with her husband Ernst was forced to flee Germany and her adjustment to a new life in England. Annie Freud’s essay ‘In the Picture’ conveys a vivid description of Lucie, to whom she was very close, and the generative role she played in her son’s art.

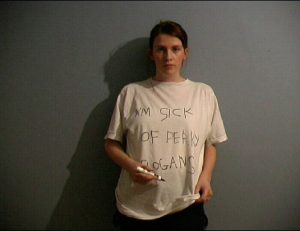

Especially curated to accompany The Artist’s Mother project is The Maternal Gaze, a series of 22 short videos by artists, writers and creatives invited to participate, including the collective Art Nomads, members of IMMA’s Visitor Engagement Team, and participants of Studio 10, one of IMMA’s most popular gallery and studio-based programmes. Produced by Patricia Brennan and Domnick Sorace, the videos shine a light on enduring inter-generational family relationships. Through images, texts and poems they variously reflect on the role of mothers and carers in our lives, the bonds of creativity and intellect in the context of contemporary discussions of motherhood.

15 3/4 x 15 3/4 in © Courtesy the artist and Victoria Miro.

We are living through extraordinarily difficult times globally particularly for women and mothers in many parts of the world such as Yemen, Syria, Mexico, Myanmar, China. In Ireland too where the weight of oppression by church and state in the 20th century continues to reveal its impact on personal histories, most recently in the Mother and Baby Homes report which continues to unfold.

This exhibition holds many valencies including a context for thinking about motherhood and the variety of family structures that exist today and how related cultural norms and expectations are re-negotiated. In all its elements it reflects the complications of creativity as well as revealing a world of women who perform the endlessly fraught interdependency of creative practice and everyday survival.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Please visit The Artist’s Mother webpage to view the virtual exhibition The Artist’s Mother: Lucie and Daryll, and listen to the poem Hiddensee, 2019, and essay The Life and Cultural Milieu of Lucie Freud, 2021 by Annie Freud.

Please click here to view The Maternal Gaze video series.