Statue Wars

In this article Lisa Moran, Curator of Engagement and Learning Programmes, IMMA, considers the current debates about the role of statues and monuments in terms of the role of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham as a former repository for unwanted or endangered colonial-era monuments and statues following the Irish War of Independence.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………

‘That’s how it goes with monuments. Some of them are put up too soon, and then, when the era of their particular notion of heroism is past, have to be cleared away’. Günter Grass, Crabwalk, 2004.

When talking of monuments the observation by Austrian writer Robert Musil, that ‘there is nothing in this world as invisible as a monument’ is often cited to point to the built-in obsolescence of a certain form of figurative, heroic monument found in urban public spaces.[1] Yet, the events of the last few weeks suggest otherwise, that these statues are not invisible, neutral or benign. The recent toppling of the statue of Edward Colston in Bristol, a man whose wealth derived from slave trading, has been a very visible and symbolic feature of the current protests against systemic racism and police brutality. It is not an isolated event and draws on a long tradition of monumental decommissioning. Since the end of the Cold War statues of Lenin and Stalin were destroyed or removed from public spaces in countries which were part of the former Soviet Union. In 2003, following the invasion of Iraq, the toppling of the statue of Saddam Hussein was broadcast around the world. More recently, we have seen the ongoing and contested removal of statues of key figures associated with the Confederacy in America.

It seems that Musil underestimated the symbolic currency of such statues and their capacity to function not only as signifiers of injustice and oppression but to actually embody these qualities. This was evident in the cathartic experience derived by Iraquees who hit the broken statue of Saddam Hussein with their shoes while dragging it through the streets of Baghdad. Rolling Colston’s statue through the streets of Bristol and into the River Avon seemed to also evoke a similarly cathartic affect.

Ireland has also experienced a period of statue wars in the decades following the Irish War of Independence (1919-1921), although this might be more accurately described as guerrilla warfare, where statues and monuments associated with British Imperial rule tended to be removed ‘by law or dynamite’.[2] Before the Royal Hospital Kilmainham became home to the Irish Museum of Modern Art, in 1991, it had been a temporary refuge for some of these colonial-era statues that had been removed from public spaces such as that of Queen Victoria, by John Hughes, R.H.S, and those of Field-Marshall Gough and Lord Carlisle, both by John Henry Foley. The statue of Field-Marshall Gough perched on his horse in the Phoenix Park was subjected to several attacks and in one such incident the head was sawn off and thrown in the River Liffey. In 1957, following an explosion which caused considerable damage to the sculpture, the remnants were removed to the sanctuary of the Royal Hospital. The statue of Gough and his horse was repaired and now stands in the grounds of Chillingham Castle, in Northumberland. A request to have the statue re-instated in 1988 was refused on the basis that the conditions in which it had to removed remained unchanged.[3] The statue of Lord Carlisle situated in the People’s Park was blown off its plinth a year later, in 1958, and the damaged work was brought to the Royal Hospital Kilmainham.

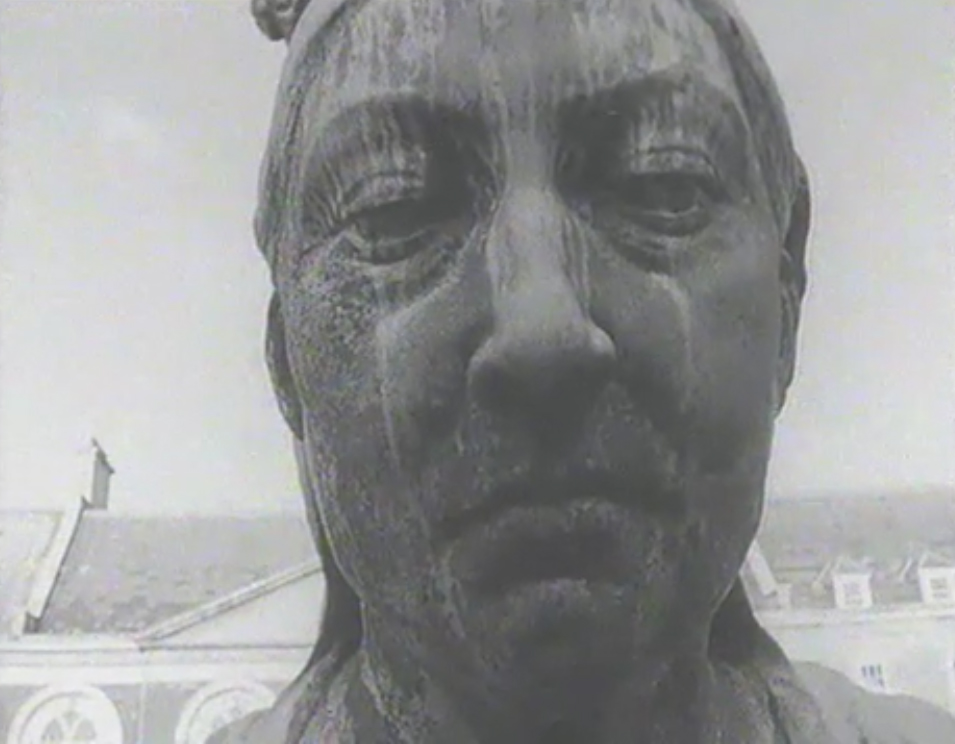

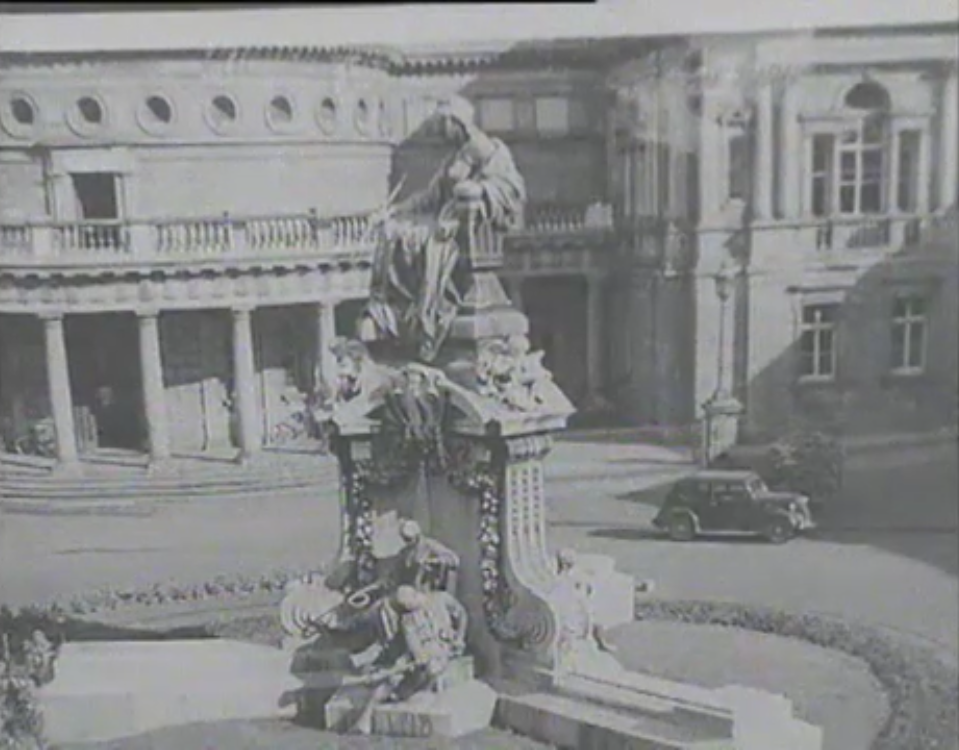

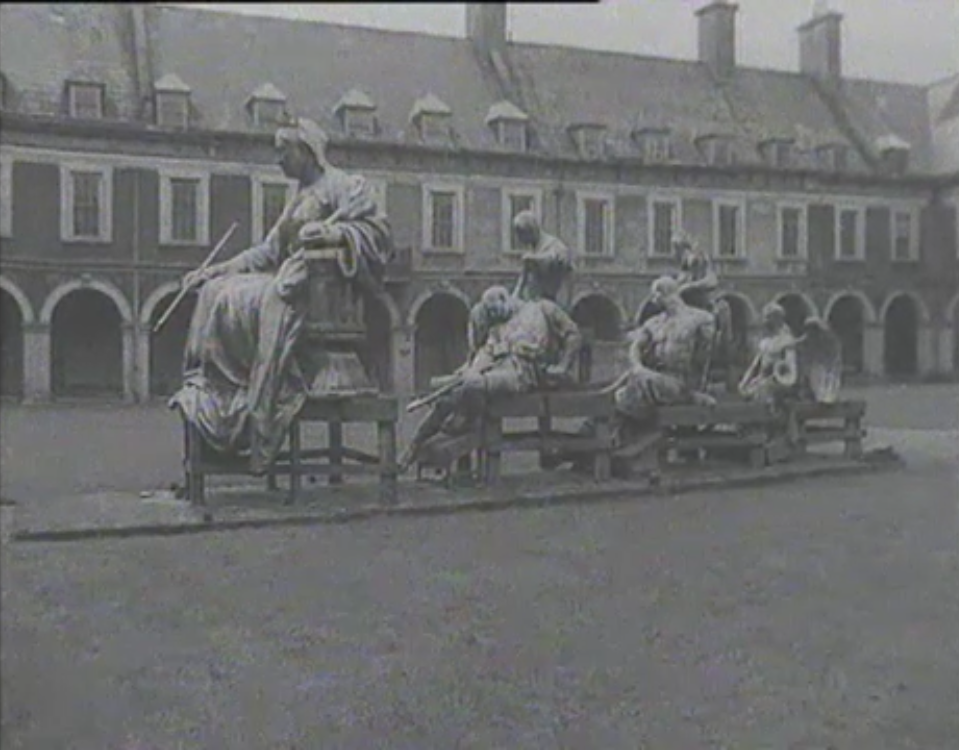

However, it is the fate of the statue of Queen Victoria that is most commonly associated with this phase of the statue wars in Ireland. In 1908, to mark the occasion of her visit to Ireland in 1901, the statue had been installed in front of Leinster House, which became the seat of the Irish government in 1922. Following a long campaign of protest the statue was removed, in 1948, to the Royal Hospital Kilmainham, where she sat in the centre of the courtyard along with several figures that had formed part of her elaborate plinth.

They were arranged on a wooden structure that created the strange impression they were setting off on an excursion with Victoria at the helm. Victoria was eventually moved to a storage facility in Co. Offaly and, in 1986, she was gifted to the city of Sydney, Australia on the occasion of their bicentenary celebrations. She now sits on a new plinth in the Bicentennial Plaza, adjacent to the Queen Victoria Building and facing Sydney’s Town Hall. She travelled alone and parts of her plinth and the figures which decorated it can be found in several locations around the grounds of the Royal Hospital.

As we have seen more recently, the destruction or removal of monuments, when ‘they fall out of favour’ evokes much heated debate about their fate, where some argue their removal constitutes an erasure or editing of history, while others suggest, in keeping with Musil’s observation, that statues and monuments tell us little about history except that it is constructed through processes of selections and exclusions. These debates present an opportunity for fresh thinking about the modes and contexts for memorials and monuments not only of the past but of the present and future.

Dr Lisa Moran, Curator: Engagement & Learning, IMMA.

The subject of the monument and its relationship to the state will be discussed further during the IMMA International Summer School 2020 ‘statecraft’. For further details and information on public events click here.

All images except the last one are stills taken from a short RTÉ news report ‘Queen Turns Green at Royal Hospital’ by Cathal O’Shannon, for ‘Newsbeat’, broadcast on 13 January, 1967.

https://www.rte.ie/archives/2017/0110/843928-queen-victoria-in-kilmainham/

[1] Robert Musil, Nachlass zu Lebzeiten (1936), published in English in Posthumous Papers of a Living Author, trans. Peter Wrostman, Eridanos Press, Hygiene, Colorado, 1987, p. 61.

[2] The Irish Times, 7 September, 1943.

[3] Irish Times, December 29, 2018, https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/state-papers-repatriation-of-phoenix-park-equestrian-statue-not-permitted-1.3735857

[4] Irish Times, December 29, 2018, https://www.irishtimes.com/culture/heritage/state-papers-repatriation-of-phoenix-park-equestrian-statue-not-permitted-1.3735857

Watch

RTÉ Archives. Queen Turns Green At Royal Hospital (1967)

Further reading

Paula Murphy, Nineteenth-Century Irish Sculpture: Native Genius Reaffirmed, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 2010.

Florian Matzner, ed., Public Art: A Reader, Hatje Cantz Publishers, 2004.

Harriet F. Senie and Sally Webster, Critical Issues in Public Art: Content, Context, and Controversy, Smithsonian Institution Press, 1998.

Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America,

Princeton University Press; New edition, 2018.

James E. Young, The Stages of Memory: Reflections on Memorial Art, Loss, and the Spaces Between, University of Massachusetts Press, 2016.

Listen back

The Artist & The State Symposium. Chaired by Mick Wilson. Listen here.

Art | Memory | Place Seminar. ‘Centenaries: What are they good for? Ann Rigney. Listen back here.

Art | Memory | Place Seminar. ‘Memory of Media in Contemporary Art’, Andreas Huyssen. Listen here.

Categories

Up Next

The Secret Seven Go Fly at IMMA

Fri Jul 10th, 2020