In this article, Charlotte Salter-Townshend writes about the biodiversification of IMMA’s artist in-residence Clodagh Emoe’s sited project Crocosmia ×. Reflections on a Radical Plot offers insights into the journey and multifaceted engagements of Crocosmia × woven together with histories, folklore, and symbolism of Crocosmia and the various species of plants which have presented themselves in the plot on IMMA’s front lawn. Encouraging nature to take its course, the text prompts notions of what it means to journey somewhere unintended, the celebration of inclusivity and being as a process. A short film of the same title, Reflections on a Radical Plot by Emoe contextualises the journey of the project to date, as IMMA on a new pilot project titled Seed STUDIO growing from this time and research.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Introduction

Clodagh Emoe creates works that explore how meaning is formed through our connection with each other and the natural world. Her collaborative project, The Plurality of Existence… (2015-2018) with individuals seeking asylum led organically to Crocosmia ×, a participatory project that was also developed and realised with individuals seeking asylum. Crocosmia × was commissioned by ‘…the lives we live” Grangegorman Public Art and supported by IMMA. The artwork Crocosmia × found a natural home in IMMA, as a plot of wildflowers on the lawn of this stately building.

When sitting by this artwork I am reminded of the concept of biophilia. Biologist Edward O. Wilson defines biophilia as “the urge to affiliate with other forms of life”[1]. Humans possess an innate tendency to seek connections with nature and other forms of life. Studies indicate the value of plants both wild and cultivated on human well-being. Increasingly, researchers acknowledge the importance of daily contact with nature. Even the ‘plucky plants’[i] that find their niche in urban environments have manifold positive effects. Growing on walls, in gutters, between cracks in the pavement, and along railway lines, these wild plants provide much needed refuge and food for animals including pollinators, but they also have a positive effect on human well-being. If our built up areas were suddenly stripped of all green living things, we would lose an oft overlooked but vital connection to the natural world. Wilson calls for humans to leave aside half the Earth’s land and sea in order to reverse the biodiversity crisis and ensure species have the space they need to thrive.[2] However, given the increasing urbanisation of the globe, cities must also play a central role in the conservation of global biodiversity. We must allow space for wild species to thrive alongside people in our urban environments.

Crocosmia × is most vibrant in late Summer, when the vibrant orange flowers of Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora are in bloom. Planted by Clodagh, Hallah Farhan Dawood, Ragad Farhan Dawood, Papy Kahoya Kasongo, Romeo Kibambe Kitenge, Marie Claire Mundi Njong, Siniša Končić,, Fatemeh, Mohamad, and friends, it is a gentle reminder and a positive symbol of the challenges and obstacles overcome by those displaced by political, social, and environmental issues. Crocosmia × symbolises the persevering spirit of plants and people who make Ireland their home.

From The Plurality of Existence… to Reflections on a Radical Plot

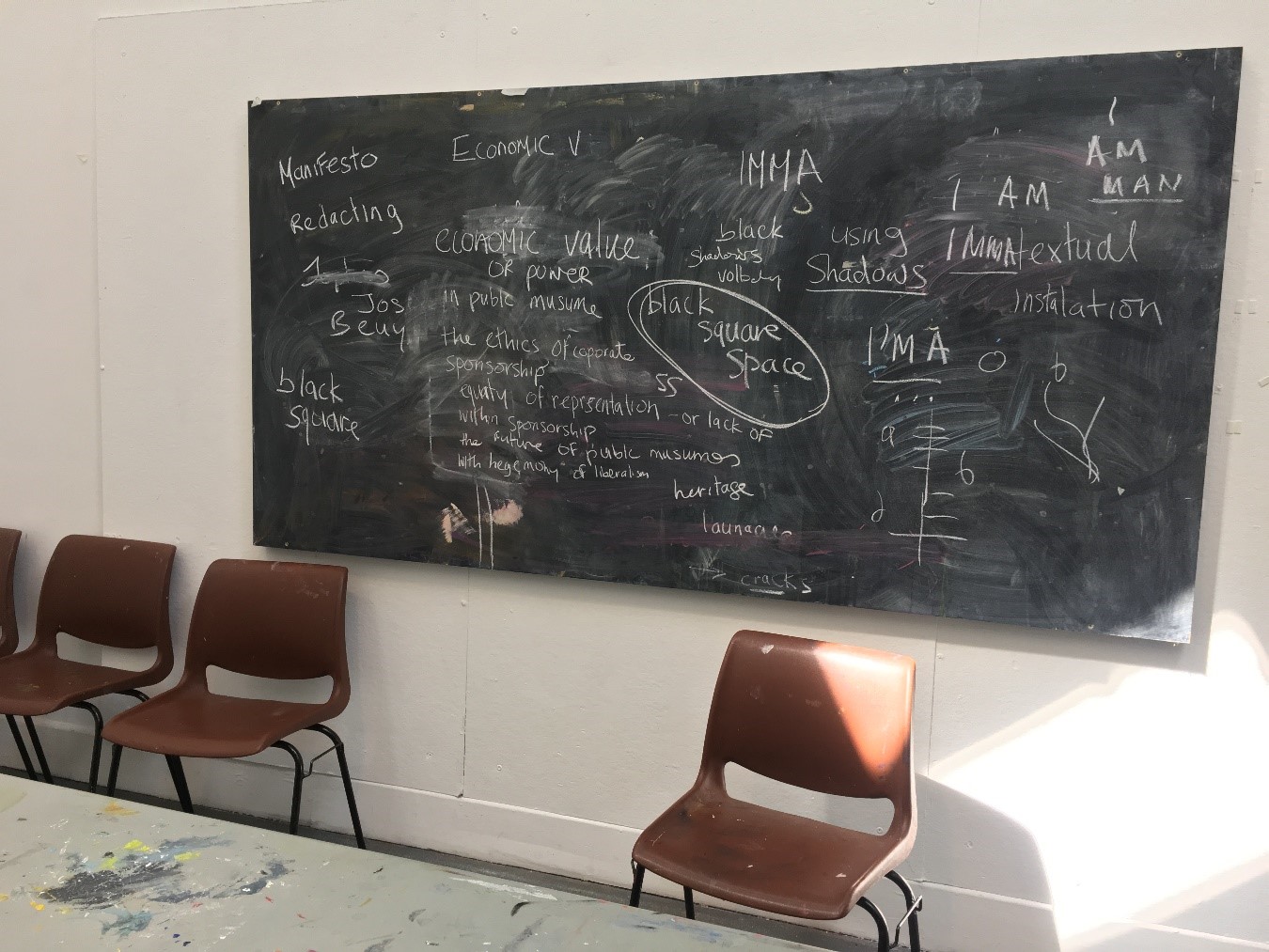

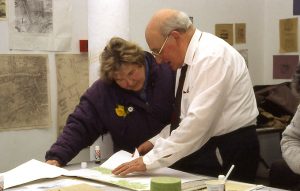

The Plurality of Existence… is collaborative art project that Clodagh initiated with a group of individuals seeking asylum in Ireland in partnership with Spirasi. Many of the group were living within the system of Direct Provision. Spirasi is Ireland’s only organization helping survivors of torture who are asylum seekers, refugees, or other disadvantaged migrant groups. As outlined in her essays on this multi-layered project and through our conversations, I learn that her motivation for initiating the project was to create a space of representation, a space to “re-present hidden narratives from the unique perspective of those who are not represented in, or by, the legislative, cultural and political frameworks within our society” and how she wanted to “create a space in the public realm for the voice of the asylum seekers and migrants living in Ireland and draw attention to the plight of so many enduring the system of direct provision”.[3] Clodagh established a gardening group which she maintains set the foundations of the project by establishing a “shared space”.[4] Clodagh speaks of their finding a corm of the plant Crocosmia x crocosmiiflora, a hybrid of two African species that is found all over Ireland (commonly known here as Montbretia, back-to-school flower, and fealeastram dearg). The group formalised their collaboration with the name Crocosmia because they believed that it offered a “symbol of hope for the group, after being themselves uprooted and forced to leave their homeland and create a new life for themselves in a foreign land”. [5] The Crocosmia collaborators are: Marie Claire Mundi Njong (Cameroon), Siniša Končić (former Yugoslavia), Jean-Marie Rukundo Phillemon (Rwanda), Annet Mphahlele (Uganda), Saida Umar (Pakistan), and Peter Rukundo (Rwanda). Members of Crocosmia began writing poems. These poems informed a series of site-specific work – poems of Crocosmia, recited in the writers’ native language and English, echoing across rivers in Cork, Carlow, Dublin, and Galway. An anthology of the poems of Crocosmia was launched in 2017 with proceeds going directly to MASI (Movement of Asylum Seekers Ireland).[6]

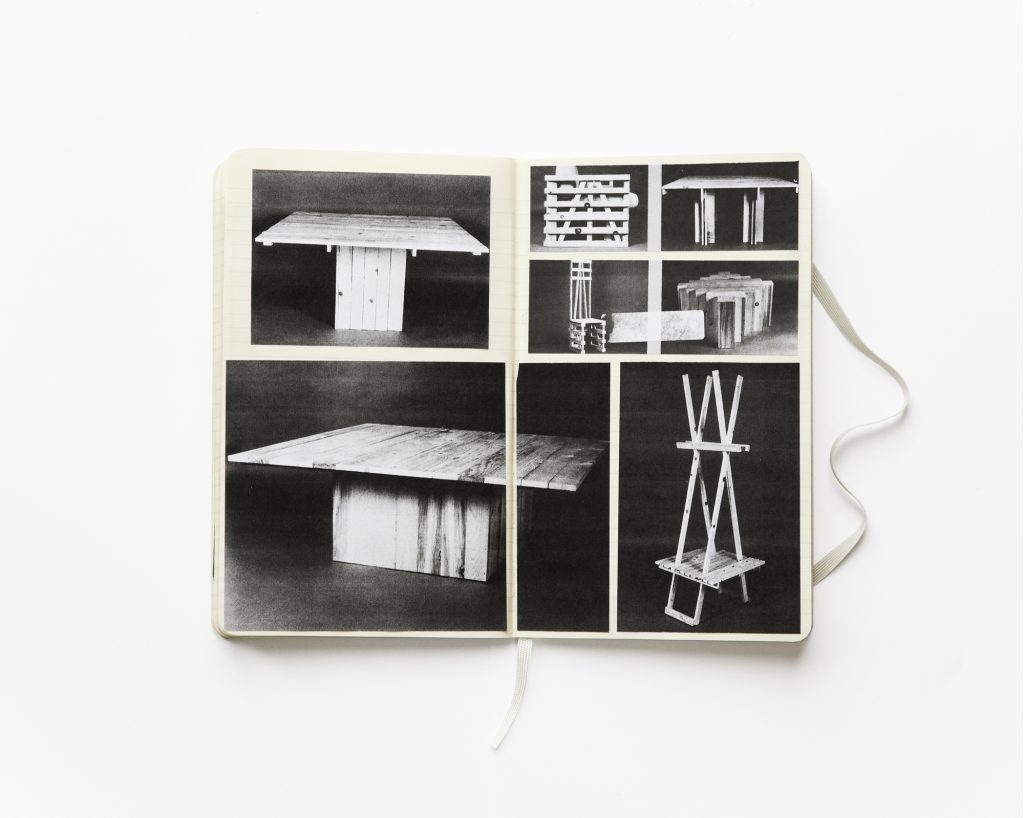

Thus opened a new chapter, leading to the project Crocosmia ×, which extended out to the wider community. The poems of Crocosmia were exchanged for specimens of the Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora with gardeners all over Ireland. These plants and the poems of Crocosmia were used in workshops to explore Crocosmia × as a metaphor for diversity in Ireland with children and young people in local schools. “By gathering, nurturing and planting Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora in local schools and on site in Grangegorman and IMMA (Irish Museum of Modern art) we aim to promote this wild flower common to Irish roadsides and native to South Africa as a new metaphor for diversity in Ireland that questions received notions of what is ‘native’ and what is ‘foreign’.”[7]

Crocosmia × refers to Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora, a hybrid of two African species. The genus name Crocosmia comes from the Greek ‘krokos’ (saffron) + ‘osme’ (smell). It is a member of the Iris family. In 1880 in France, Victor Lemoine hybridised Crocosmia aurea and Crocosmia pottsii. C. aurea is a woodland plant while C. pottsii grows in nutrient-rich ground near streams. The resulting hybrid likes damp ground and sunshine. It became a successful and popular Victorian era garden plant, a feature in the best herbaceous borders in Britain and Ireland. However, some gardeners found it spread too quickly, forming large clumps. It spreads vegetatively via corms, a bulb-like organ. The plants and corms were dumped in hedgerows and soon became a feature of countryside roads and railway tracks in Ireland. By the early 1930s, according to Sylvia Reynolds (A Catalogue of Alien Plants in Ireland, 2002) it was frequent in the wild.

Today it is as ubiquitous as Fuchsia magellanica, a garden escapee of Chilean origin that has become a symbol for West Cork. Both Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora and Fuchsia magellanica are classified as invasive plants, but are not treated in the same way as Himalayan balsam or Japanese knotweed. Perhaps this is because they do not encroach but coexist with their neighbours. The terms native and invasive are both subject to debate even in scientific discussion. Ask a botanist what native means and they say consistently present in a given geological timeframe. In Ireland, we typically say present since at least the recolonization of plants at the end of the last Ice Age. Some plants remained here throughout the Ice Age. Some died out and were reintroduced by people later on. Should they be considered as natives? The term is not necessarily a fixed one. Invasive refers to species that are introduced and have a tendency to spread to an extent that causes damage to the environment, human economy, or human health. There are widely divergent perceptions amongst plant researchers. Native species can themselves overpopulate and become invasive – for example, the Burren is an area particularly rich in plant diversity, due in part to the control of the native hazel scrub through centuries of agriculture. In Ireland, there are no fully natural grasslands (like the savannah in Africa) – rather, the removal of woodland in the past sometimes allowed for specialist species of wildflowers to find their niche in open areas. Of course, grassland biodiversity has come under threat ever since the ‘green revolution’ in agricultural practice. Context is key for every case.

In the Crocosmia × project, parallels are drawn with different cultures that have entered Ireland. As the world becomes smaller, and people and plants are on the move more and more, what is the definition of native and invasive? The mission of botanic gardens, according to Botanic Gardens Congress International, is to protect and promote diversity of plants for the well-being of people and planet. To this end, every plant type is precious.

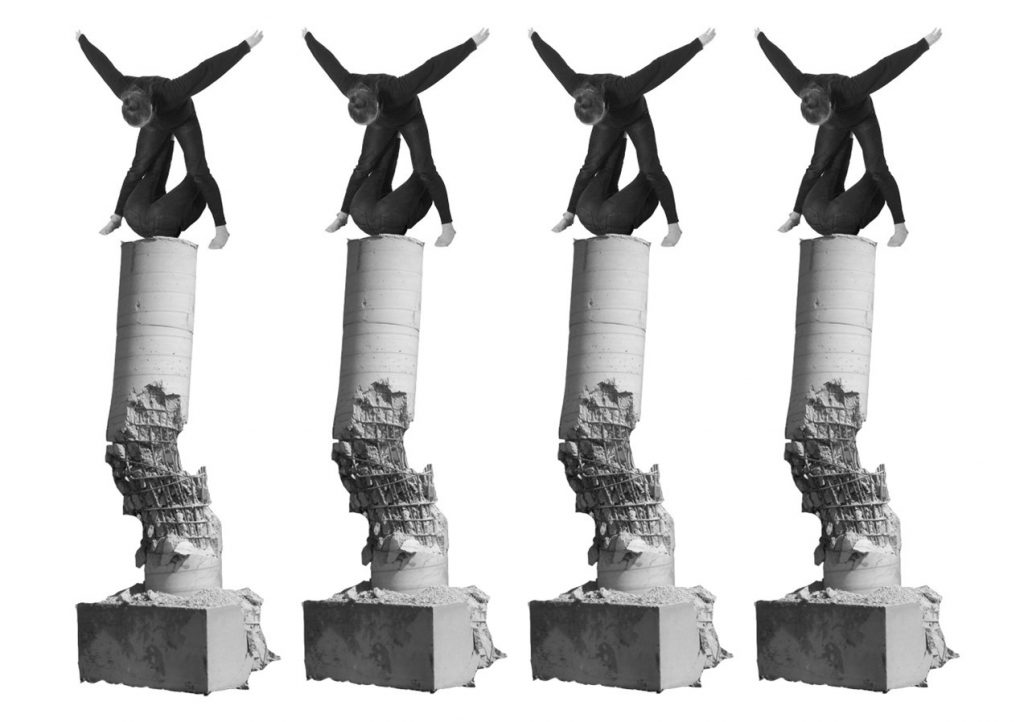

Since the Crocosmia × plot was planted at IMMA in 2018, other plants have self-seeded there, brought in from large garden estates, rural farms, suburban gardens, and inner city backyards with the specimens of Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora that were exchanged for the poems of Crocosmia. The appearance of new plants has also resulted from seeds dispersed by the animals and birds that use and pass through this plot, a site in flux, ever changing. When speaking to Clodagh she remarks excitedly on this unanticipated outcome. How it surprised her particularly because Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora is deemed ‘invasive’ by the Department of Agriculture and yet here we see a diverse range of plants in harmonious coexistence. She remarks on this “quiet progression” and how this exposes the idea of diversity that informed this artwork. For Clodagh this development “makes sense” in the way that it demonstrates her understanding of art as an “open process”, a thing that evolves and is never fixed, as she maintains, “it’s art’s resistance to order that allows us to formulate our own meaning, presenting moments of potential that ‘invite’ thought”.[8]

Ordering nature

Human tendency is to generalise and categorise things, in order to comprehend and recall the great diversity of the natural world. In the 18th century, Carolus Linnaeus revolutionized the field of natural history by introducing a formalized system of naming organisms – taxonomic nomenclature. He divided the natural world into kingdoms and used ranks such as class, order, genus, species, and variety. With new discoveries and understanding over the intervening years, the system has been refined, with countless organisms added or reclassified. Despite its utility, taxonomic nomenclature is a human invention and not an objective reality – living things will always skirt and subvert our expectations and categories.

Despite the scientific method’s emphasis on objectivity, scientific institutions are subject to bias. The language of nomenclature belies its European colonialist and patriarchal origins, using terms such as kingdom. With the advent of an official scientific naming system, ordering and defining nature often developed as a way of controlling things – the colonial mind-set was to control nature as well as people. Naming is power. As Linnaeus declared: ‘God created, Linnaeus named’. Unfortunately, a lot of folk knowledge of the natural world has been lost over the years. In Ireland for example, countless traditional uses of plants for food, medicine, and more was not recorded and was forgotten through the decline of the Irish language, famine, emigration, and other processes. We are fortunate to have some information preserved. The work of Irish Folklore Commission in 1937-38 instigated the collection of folklore throughout the National Schools of 26 counties. One hundred thousand children gathered more than a half a million pages. It was of paramount importance in recording many things, including folk remedies and local lore. Reflections on a Radical Plot, engages with this aim to preserve. Clodagh endeavours to identify and archive acknowledge of these plants and their value. Plants referenced in the collection of folklore are brought back to our attention in her organic, ghostlike prints of nettle, forget-me-not, primrose, herb Robert, ribwort plantain, nipplewort, prickly sow thistle, common thistle, opium poppy, wild violet, and western willow herb.

Nettles are nutritious and are an example of food as medicine: “Three doses of nettles in the month of April will prevent any disease for the rest of the year”.[9] Nettles are also vital for wildlife, the leaves providing food for the caterpillars of small tortoiseshell, comma, red admiral, and peacock butterfly. The stinging hairs protect the plant from grazers, allowing all sorts of insect life to thrive undisturbed. Nipplewort is a ‘weed’ of cereal crops. It has become less frequent with modern agricultural practices. The flower buds were thought to resemble nipples. Hence, it was believed to help heal sore nipples. This is an example of a theory known as the doctrine of signatures, popular in medieval times. Willowherb is also known as fireweed, because it grew where bombs had struck during the Blitz in London. It is a plant symbolic of upheaval and survival. Dandelions are considered the classic ‘weed’. Originating in Europe and Asia, it is estimated that dandelions have been in cultivation since the Roman times. They are used as remedies for illnesses including liver problems, gastrointestinal distress, fluid retention, and skin ailments. The plant is also a tasty and highly nutritious vegetable. During the seventeenth century, European colonists introduced dandelions to North America. Native American peoples also developed their own uses of the dandelion after it naturalised.

Being as a process

For the purposes of scientific record, botanists and collectors press and preserve plants as herbarium specimens. Bridging across science and art, botanic artists paint plants with great accuracy and detail. Clodagh develops this further, using unique ecological printing process that captures an image of the subject using the very essence of the plants. What appears as a mirror image reveals the trace of natural dye from the front and back of the plant left on each page, a duality presenting the plants’ dimension and depth, like the poetry of the asylum seekers who collaborated in The Plurality of Existence… and Crocosmia ×. This ecological printing process captures the complexity of these plants, revealing that being is a process in constant flux and in dialogue with the environment. At times, plants are potential, lying dormant in the soil. Later, they decay and return to the earth, showing us that death is just a part of the life cycle. “Deep in their roots all flowers keep the light” – Theodore Roethke.[10]

Plants challenge our notion of individuals. Clodagh’s prints show that each plant has characteristics outside of its species designation. Yet according to the definition of individual, plants do not qualify. An individual is characterized by the fact that it is indivisible: if you cut it in two, you kill it. However, if you cut a plant in two, it does not die. You can propagate plants this way, such when the Crocosmia × crocosmiiflora were divided and shared in the community for Crocosmia ×. Now a variety of other plants have joined the Crocosmia x plot. They were not sown by human hands but arrived of their own accord. Their seeds blew in on the wind or were dropped by animals. The plants have made the plot their home and now they form a community which will endure with new additions and future generations of plants. When viewing the plot at IMMA, we see a habitat where the lines between individuals are blurred. It is a microcosm of the larger environment. As Siniša Končić’s poem Vukovar, Croatia goes: “One bench. All my world.”[11]

In recent times, efforts are made to establish that diversity is the natural state of being. Each living thing has relationships with those around it. We are only scratching the surface of the depth of the symbiosis between living things. To this end, we must see both the wood and the trees as part of an intricate tapestry, a “plurality of existence”.[12]

[1] Wilson, E.O., 1984. Biophilia. Harvard University Press.

[2] Wilson, E.O., 2016. Half-earth: our planet’s fight for life. WW Norton & Company.

[3] Emoe, C “The Plurality of Existence… ”, 2020. New Cartographies, Nomadic Methodologies: Contemporary Arts, Culture and Politics in Ireland, ed. Anne Goarzin & Maria Parsons, Peter Lang, London, Oxford, New York.

[4] Emoe, C., 2020. “Approaching an Understanding of Place”, Public Art Now, ed. Haughton and Keeve, GGDA.

[5] The Plurality of Existence in the Infinite Expanse of Space and Time, 2017. ed. Clodagh Emoe, Dublin.

[6] MASI is an independent platform for asylum seekers to join together in unity and purpose. The collective seeks justice, freedom and dignity for all asylum seekers. https://www.masi.ie/

[7] Emoe, C., 2022. Crocosmia ×. https://www.clodaghemoe.com/

[8] Emoe C., 2014. Exploring the Philosophical Character of Contemporary Art Through a Post-Conceptual Practice, PhD. https://arrow.tudublin.ie/appadoc/51/

[9] UCD (2022). National Folklore Collection Schools. https://www.duchas.ie/en/cbes/4713251/4711478/4715049

[10] Mabey, R. and Sinclair, I., 1973. The unofficial countryside. London: Collins.

[11] Končić S., 2017. “Vukovar, Croatia” from, The Plurality of Existence in the Infinite Expanse of Space and Time ed. Clodagh Emoe, Dublin.

[12] Emoe C., 2017. “Foreword” from The Plurality of Existence in the Infinite Expanse of Space and Time ed. Clodagh Emoe, Dublin.