At Home With Louise

As a member of the Visitor Engagement Team at IMMA I have a bit of a dilemma. How do I approach doing my job from home during this period of isolation?

The work I do revolves around connecting with people in the physical context of the museum. Collaborating with my colleagues in the Visitor Engagement Team to create workshops, tours and projects to deliver in real time and space to individuals and groups from schools, colleges and the community. Invigilation is part of the job description and while we have the privilege of sitting in the gallery taking care no harm comes to the artworks in our charge, we can use this time also to research for upcoming tours, projects and exhibitions. Being present in the gallery affords us the opportunity to engage with our visitors, be available to them to answer questions about the art and engage in conversation and debate.

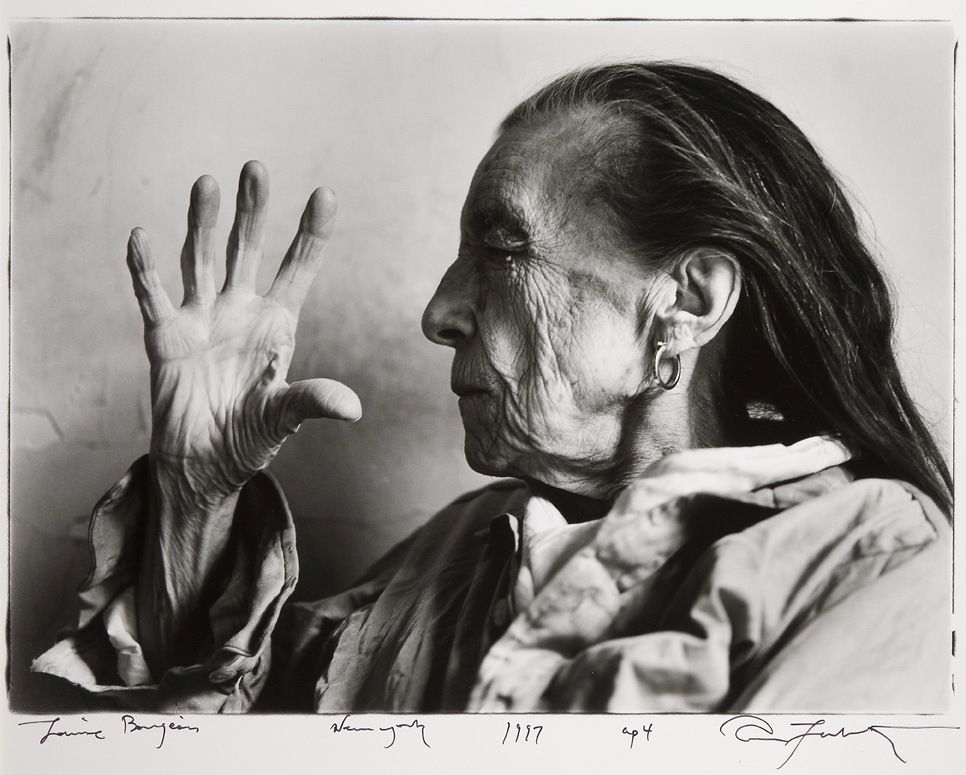

So how do I do my job in the void, without the grist to the mill that is the public? Over the first week as I searched for inspiration, an image kept coming to mind. A photograph by Annie Leibovitz from the museum’s collection. I’m going to trust my intuition and see where this image leads me.

Annie Leibovitz was born in Connecticut in 1949. Her mother was a musician,painter and teacher of modern dance. Her father was in the American Air Force. The family moved around a lot, living on various military bases in America and abroad. During the Vietnam war the family lived on an air base in the Philippines where Annie’s father was posted for the duration of the war. During this time she began taking photographs around the base and local village.

She later attended the San Francisco Art Institute where she initially studied painting but changed her major to photography after doing a workshop which rekindled her interest in the medium.

During her career she worked for Rolling Stone Magazine and later for Vanity Fair, photographing celebrities, royalty and athletes. She did a photo shoot for John Lennon and Yoko Ono on the day John was assassinated. However it’s the subject of this portrait that is my inspiration. The picture is of Louise Bourgeois aged 85. She is in profile, hair slicked back, staring at her hand. She represents for me in this image a primal energy that maybe I can tap into.

I’m going to take a thread from the rich tapestry that is the life and work of Louise Bourgeois and see where it leads. This thread brings me back in time to Paris, Christmas Day 1911, the day Louise Bourgeois was born. She was the second daughter – her sister Henrietta Marie Louise was born on the 4th of March 1904. Both daughters were named after their father, landscape architect Louis Bourgeois. Baby Louise was given her father’s name to compensate for her not being a son.

Josephine Fauriaux, Louise’s mother, ran the family’s Medieval and Renaissance Tapestry Gallery at Maison Fauriaux, 212 Boulevard Saint Germain. The year after Louise’s birth the family moved from Paris to a rented mansion 11 km from Paris in Choisy-le-Roi. This house would be the subject of several of her future art works. Here they set up an Atelier for restoring antique tapestries. Louis Bourgeois was the face of the family business and he traveled around France sourcing tapestries. The textiles were often damaged and the restoration was carried out by Josephine and her team of weavers at Choisy.

The following year, Pierre Joseph Alexander was born into the Bourgeois family. Soon after the birth, Louis was conscripted into the army and Josephine moved with her three children to stay with her parents at Aubusson, the epicenter of the tapestry weaving industry in France.

After the war they set up another Atelier, this time in the district of Antony. The arrangement here was very suitable, the house had an Atelier to the rear and the garden was right on the banks of River Bièvre which was rich in mordants essential for fixing dyes in the process of restoring the tapestries. Louise’s childhood here was happy. She loved being around her mother and the other tapestry workers, joining them when they brought the huge textiles to the river to be washed.

By the time she was twelve her drawing skills were so adept that she was brought into the family business to draw templates of the damaged and missing parts of the tapestries, and before long she was stitching and repairing alongside her mother and the other women.

A young English governess, Sadie Gordon Richmond, was hired to teach the Bourgeois children English. Louise was besotted with her and when Sadie went home for holidays to England, Louise wrote to her often beseeching her to return as soon as possible. The dynamic changed dramatically however when it became apparent that Sadie was in fact the mistress of her father and openly lived and slept with him in the family home. This betrayal haunted Louise all her life.

Family meal times were excruciatingly difficult for the young Louise. Her father’s larger than life personality was inescapable and was expressed in full force around the dinner table. He was known to encourage dinner party guests to perform a party piece. His own trick was to dramatically take up a tangerine at the end of the meal and announce to the company that he was going to make a portrait of his daughter. Here he would turn and look directly at Louise, then proceed to draw and cut out a little figure from the surface of the orange. He would then remove the figure and hold it up for all to see, before turning it around to reveal a little pithy ‘penis’ stem and saying “Oh but this can’t be my daughter because she has nothing down there.” The entire assembled company laughed and clapped at his sadistic performance. To help herself through these charades Louise would make little bread sculptures, effigies or her father that she would dismember to assuage her repressed anger – bread for the hunger no one sees. She began keeping a diary at this time, a practice that she would continue over her lifetime.

In the early 1930s Louise took up a course in mathematics and pure Geometry at the Sorbonne. She also studied philosophy, writing her dissertation on Emmanuel Kant and Blaise Pascal.

Her education was halted in 1932 when her mother became ill. Louise dedicated herself to nursing her, a role she had stepped into on many occasions in the past. In September of that year her mother died.

Louise’s life changed dramatically at that point. In 1933 she enrolled at L’Ecole des Beaux Arts to study painting, but she didn’t last long there. Louise’s eclectic nature was better suited to the diverse education she could gain by visiting a variety of artists, ateliers and academics that were peppered around Paris at that time. She studied in many different disciplines: engraving, graphics, drawing and painting, with artists such as Paul Colin, André Lhote and Fernand Léger.

She was well versed in all the art movements of the early 20th century from cubism and surrealism through Russian constructivism. She traveled widely in Europe and Russia. She also studied art history at L’École de Louvre and worked as a guide in the Louvre gallery to offset her tuition fees, the fluent English she had learned from Sadie proving useful. Many of her colleagues at the gallery were first world war veterans, several had limbs missing and got around with the aid of crutches.

Her first Paris apartment was above the gallery Gradiva, which was run by André Breton and was where the surrealists exhibited their work. In the same building there was a prosthesis maker working and Louise often encountered people coming to his atelier to have their prosthetic limbs fitted.

As the decade progressed so did Louise’s art and she began to be accepted for exhibitions at the Galeries de Paris and Galeries Jean Dufresne. In 1938 Louise opened her own art gallery in part of the family’s Paris showrooms. Here she traded in prints and paintings by artists from Eugène Delacroix to Henri Matisse. Robert Goldwater, a young American art historian on holiday in Paris after completing his book Primitivism in Modern Art, visited the gallery. Louise and Robert fell in love and married that same year. Louise later in her life described Robert as the opposite of her father, referring to him as understated, gentle and a feminist. Robert was a Jewish man and the spectre of nazism was hovering over Europe, so the couple decided to move to New York. They had three sons, all of whom were given the Bourgeois name in accordance with Louise’s father’s wishes.

Robert Goldwater was a highly regarded art historian and editor and he had many connections in the New York art scene. Through him Louise became acquainted with artists, art dealers and critics, from Mark Rothko and Willem De Kooning to Peggy Guggenheim and Clement Greenberg. She made many friends amongst the expatriate artists arriving in New York daily from war torn Europe as well as being reunited with friends like André Breton, Marcel Duchamp,and Alberto Giacometti. She threw herself again into her study and enrolled at the Art Students League and soon began exhibiting her work around New York.

Now lets travel back to Dublin, to the Garden Galleries at IMMA in 2003 and the exhibition Stitches in Time, curated by Frances Morris and the then Head of Exhibitions at IMMA, Brenda McParland.

Frances Morris was the curator of the inaugural installation in the Tate Modern turbine hall, three towers made by Louise Bourgeois, each one taller than a two story house entitled I Do, I Undo, I Redo, and a nine meter high bronze spider sculpture with a metal mesh undercarriage filled with marble eggs called Maman, in homage to her mother. Morris, now Director of Tate Modern, would return in 2015 to give a talk on the exhibition Gerda Frömel, A Retrospective, curated by Sean Kissane.

I’ve been rostered to give a tour of the exhibition so I go to meet the group at the main reception. They have traveled by train from the midlands and are excited to get started. We make our way through the courtyard to the gallery overlooking the museum’s beautiful formal gardens.

The show has 25 works, I bring the group through the reception area and down to the basement where we’ll begin.

Untitled, 1996

This sculpture has a vertical metal pole anchored to a square metal plate on the gallery floor.

It’s about 6 feet tall. Off the central pole, extending perpendicularly are eight metal rods. At the end of each rod there is a large animal bone which serves as a macabre clothes hanger for one of eight delicate feminine garments. looking at this image I imagine a strange constellation of planets revolving, the passage of time, the cycle of life, the bone and the fragile beauty.

In 1996 Louise was aged 85. At this point in her life is she taking a look at the flimsy nature of existence? She has lost her parents, her sister Henrietta, her brother Pierre, her husband Robert and her son Michel who died in 1980. We talk a lot about the piece, each member of the group finding their own key to enter this archetypal confection.

We move along to the next sculpture. en route we pass through a corridor. Hanging on the walls are a suite of nine drypoint and aquatint etchings titled Topiary: The Art of Improving Nature. The group are interested so we stop to investigate. We choose one of the prints to discuss – a tender image of a faceless soldier propped up precariously by a crutch. The crutch, although steady and upright, cannot be of any benefit – it doesn’t reach the stump of the amputated arm it’s supposed to support. On the same side of this unknown soldier, the remains of his right leg. The leg he is standing on has a foot so small it can’t possibly hold him up. Louise was also a mathematician so maybe she worked out a formula that would allow this soldier to balance, standing alone. The only colour in the image is a beautiful delicate red, emphasizing the hot pain of loss where his limbs used to be.

Spiral Woman, 2003

This is a life-size figure made from a black stretch fabric pieced together and stitched. Louise speaks of the symbolic meaning of colour in her work – black represents resented authority. The figure is dangling in space, two legs not touching the floor. From the abdomen upwards the body becomes a doughy spiral, continuing in an ever decreasing twist towards the meat hook that digs into the fleshy knot on top. The body has been rendered helpless, turned and held fast by the power of the needle and the artist’s hand, never to unravel. But no, you can’t say never in the context of Louise Bourgeois, she may well undo and redo.

Louise’s first encounter with the working physicality of the spiral was as a child standing knee deep in the Brèvre river twisting huge, heavy tapestries with her co-workers. She mentions later in life her childhood fantasies of ringing the neck of her governess Sadie, her father’s lover for 10 years.

Femme Maison, 2001

This white stretched fabric work comprises a female torso laying on its back, headless, armless, legless. Placed on top of the navel is a house made from the same fabric, featureless apart from a gaping hole where the door might be. This strange landscape is pure and pristine, still and quiet as a snow-covered landscape at the break of dawn. However this landscape is not free, it is contained within a steel framed glass case supported by four legs invoking a strange metamorphosis of table and bed.

The genesis of this work stretches decades back in time to 1946/7 to a series of paintings of the same name. Femme Maison – woman house – translates to housewife. These paintings have a surrealist feel and are evocative of Exquisite Corpse, the surrealist drawing game where participants add to a drawing of a body without seeing what others have contributed. The image of house becoming woman or woman becoming house is a strange hybrid creature raw from the unconscious of the artist.

While moving through the gallery to the next artwork we are going to talk about, some members of the group take interest in a different piece. We stop for a closer look.

Arch Figure, 1999

Another female figure made from pink fabric. This colour represents acceptance of self, forgiveness and tenderness in Louise’s personal colour coding. The arched figure suspended by a thread from the belly, like an umbilical cord too small in diameter for nourishment to pass through. Displayed like a fairground prize in a glass container, if you could only fish it out. The arched body is tense and stiff, armless, helpless, trapped between these glass walls, the pain magnified for all to see in the vanity mirror that reflects the tortured face.

Oedipus, 2003

The story of Oedipus is a tale of abandonment, loss, incest, murder, riddles and destiny.

This work, more theatrical in presentation, is made up of twelve different characters constructed and stitched from a pink fabric reminiscent of surgical bandage. These small doll-like things wait as if on stage ready to reenact this gruesome tale. Front and centre in the glass enclosure is a sphinx. At the back a kneeling figure holds a red crystal globe in her arms. A Janus style two faced bust looks in different directions. A body laying face down with a knife in his back. The sexual embrace of a couple. Incest, patricide and the masochistic infliction of blindness – the head of Oedipus faces us, pins in his eye sockets. All served up to us by Louise, a ready made story.

After the death of her father in 1951 Louise entered decades of self scrutiny through psychoanalysis. Her father’s house in France still contained hoards of garments and tapestry fragments from Louise’s childhood. Her Coco Chanel dresses from her pre-teen days and little items of clothing her mother had made for her when she was a baby. She had the lot shipped to New York. She would turn these fibers into art in the final decades of her life.

Louise had an insatiable appetite for materials to use in her sculpture. In the 1940s she worked in wood carving for the Personages Series. These vertical surrogates for her family and friends left behind in France were exhibited at the Period Gallery in New York in 1949. During the 1960s she began experimenting with a diverse range of new materials: latex, rubber and resin as well as making sculptures in bronze and marble.

We’ve all but run out of time on this tour but there is a sculpture I want my group to see before we finish.

Rejection, 2001

The image before us is of a head, beautifully constructed in white fabric, mounted on a slab of lead and encased in a glass box propped up by four steel legs. Louise made many fabric heads, stitched together from the remnants of her clothes and imagination. They are typically displayed in this fashion, facing forward and set slightly below the viewers eyeline. The expression on this face is as haunting and enduring for me as Edvard Munch’s Scream.

As we walk back to the main building together, the conversation is all about Louise. We talk about how her massive retrospective in the Museum of Modern Art, New York in 1982 was the first for a female artist in the history of MoMA and how the young artist Jerry Gorovoy came into Louise’s life in the 1980s staying with her as an assistant and loyal friend until her death on the 31st of May 2010, aged 98.

In 2005 Louise Bourgeois donated the art work Untitled, 2001 to the IMMA Collection in recognition of the success of the Stitches in Time exhibition. I’m so looking forward to seeing this particular artwork in the flesh again soon.

Categories

Further Reading

Women, feminism and art

IMMA's Lisa Moran examines the current emphasis on women and art in IMMA's 2013/4 programme, reflecting on how it draws on and highlights IMMA’s rich history of exhibitions featuring female artists, who have...

Two artists – Janet Mullarney and Tim Robinson

Here we reflect on two remarkable artists and people, Janet Mullarney and Tim Robinson, who we had the pleasure to work with and get to know over many years. Our thoughts are with their families and many fri...

Growing Wild at IMMA

We are delighted to present a new series exploring the biodiversity of the IMMA site. Although the grounds of IMMA are currently closed Sandra Murphy, from our Visitor Engagement Team, would like to share wi...

Do I lie when I say I love you?

In association with the exhibition What We Call Love, Dr Noel Kavanagh asks the question: Do I lie when I say I love you? Check out Noel's nominated pop song in his concluding reflection.

Up Next

IMMA Collection. Solitude, isolation and communication

Fri May 29th, 2020