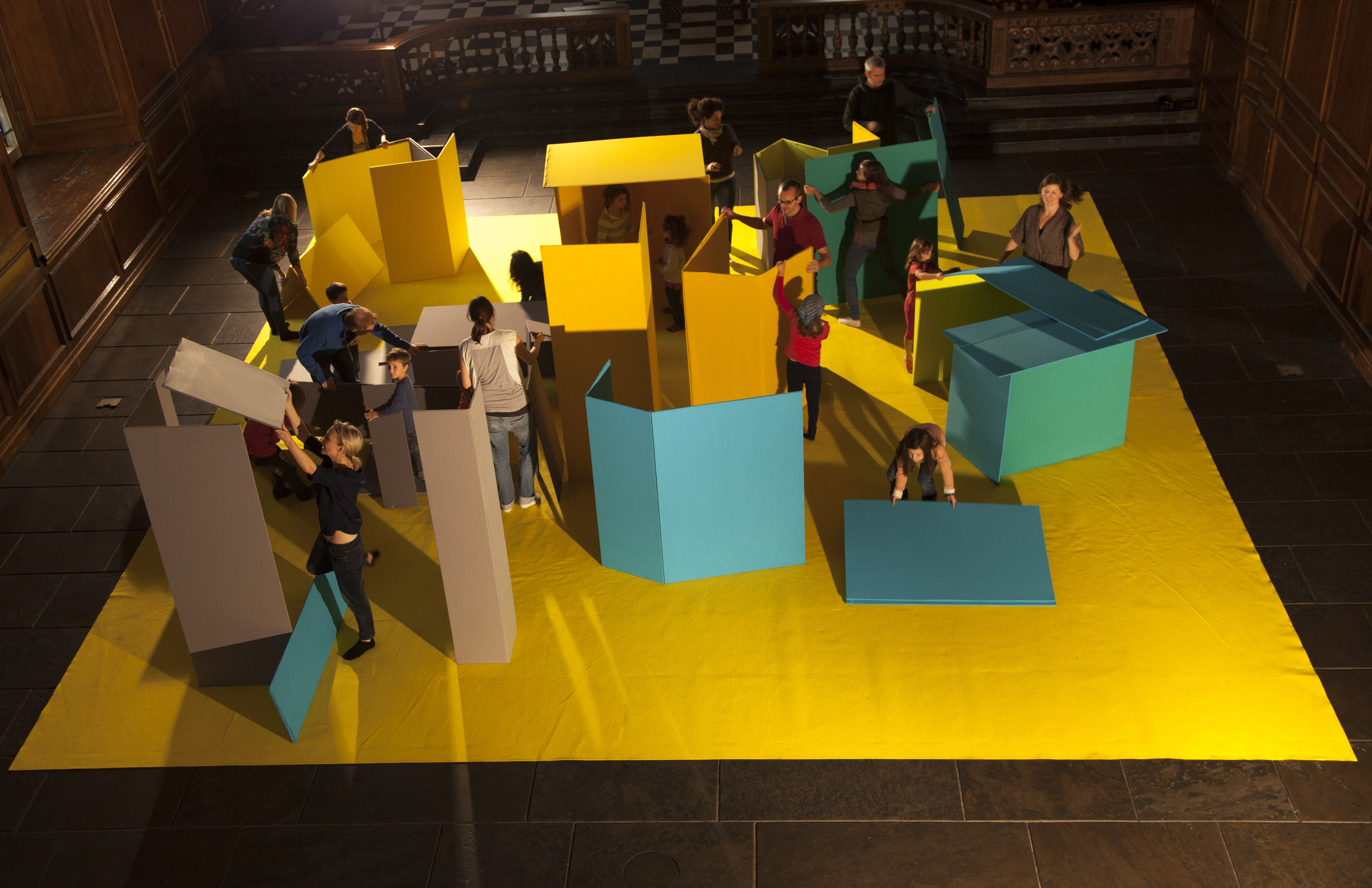

Working on In the Line of Beauty, an exhibition of contemporary Irish art in the East Ground galleries at IMMA, has been a great experience. The show was in development for almost two years, so it was wonderful to see the final result when IMMA re-opened its doors in early October. IMMA Head of Exhibitions’s, Rachael Thomas, concept developed from a keen interest in the type of work being made by artists in Ireland today, their use of unconventional and inexpensive materials and their investigations into personal narratives and relationships. The exhibition found its historical roots in William Hogarth’s eighteenth century theory of aesthetics, in particular his concept of the ‘line of beauty.’ The exhibition has shown how Irish artists respond to ideas of beauty within their practice today. We were lucky to have the engraving Analysis of Beauty Plate I, 3rd State by Hogarth in IMMA’s collection and included it as a touchstone within the exhibition.

IMMA re-opened at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham in October with four exhibitions, but the In the Line of Beauty installation started much earlier in May. It was a strange experience installing four rooms of artworks, then covering the works with dustsheets and closing the doors for four months. But this provided us with a smooth period of final preparation before the opening night. Finishing the installation of In the Line of Beauty first, and staggering the other exhibition installations afterwards meant that our great team of art technicians wouldn’t be facing an impossible task and that the artists were well rested and fresh-faced for the opening night!

Some of the works in the exhibition were created especially for the exhibition, while, for others, it was a chance to re-visit and re-interpret previously made pieces, as Fiona Hallinan did for her work Unsold (2011/2013). She collected petals from the IMMA gardens over a period of time and displayed them in the gallery as a representation of the moment they turned from having an aesthetic value to becoming waste. Previously, she had installed this work with petals collected from the floors of flower shops, therefore basing the work more in terms of monetary value and economics. Other artists took the opportunity to show a slightly different side to their work such as Ciarán Murphy who moved away from his haunting animal paintings to present a new direction of beautiful abstract images.

Once the works were installed, we commissioned photographer Davey Moor to take installation shots to be used in the accompanying exhibition catalogue (and this blog). The images were beautiful and dynamic, the essential element of the exhibition. Also, working with Moor who is a younger Irish photographer was very apt as he was photographing the works of his peers and, in some cases, his friends. Because of this, there was an energy and freshness in the images which may not have otherwise been captured.

As well as Moor’s images, the exhibition guide for In the Line of Beauty included a foreword from IMMA Director Sarah Glennie, an introduction by Rachael Thomas and some of my own thoughts on the role of beauty in contemporary art. Man Book Prize winner Alan Hollinghurst also contributed a excerpt from his novel The Line of Beauty, which was the direct inspiration for the exhibition. The novel dramatised the the dangers and rewards of the protagonist’s own private pursuits of beauty. Hollinghurst chose an extract for our catalogue that highlighted the central role of Hogarth’s ‘line of beauty.’ This further reinforced the engagement of artists such as Oisín Byrne with the intensity and intimacy of personal relationships that is vital in Hollinghurst’s book.

We worked with Pony Ltd design consultancy on the publication, and their cover illustration (based on a repetition of Hogarth’s serpentine line) cleverly expanded on the ‘line of beauty’ in a contemporary context. Developing this relationship, the size of the guide was based directly on the size and ratio of the Hogarth print in the exhibition. It bound everything together.

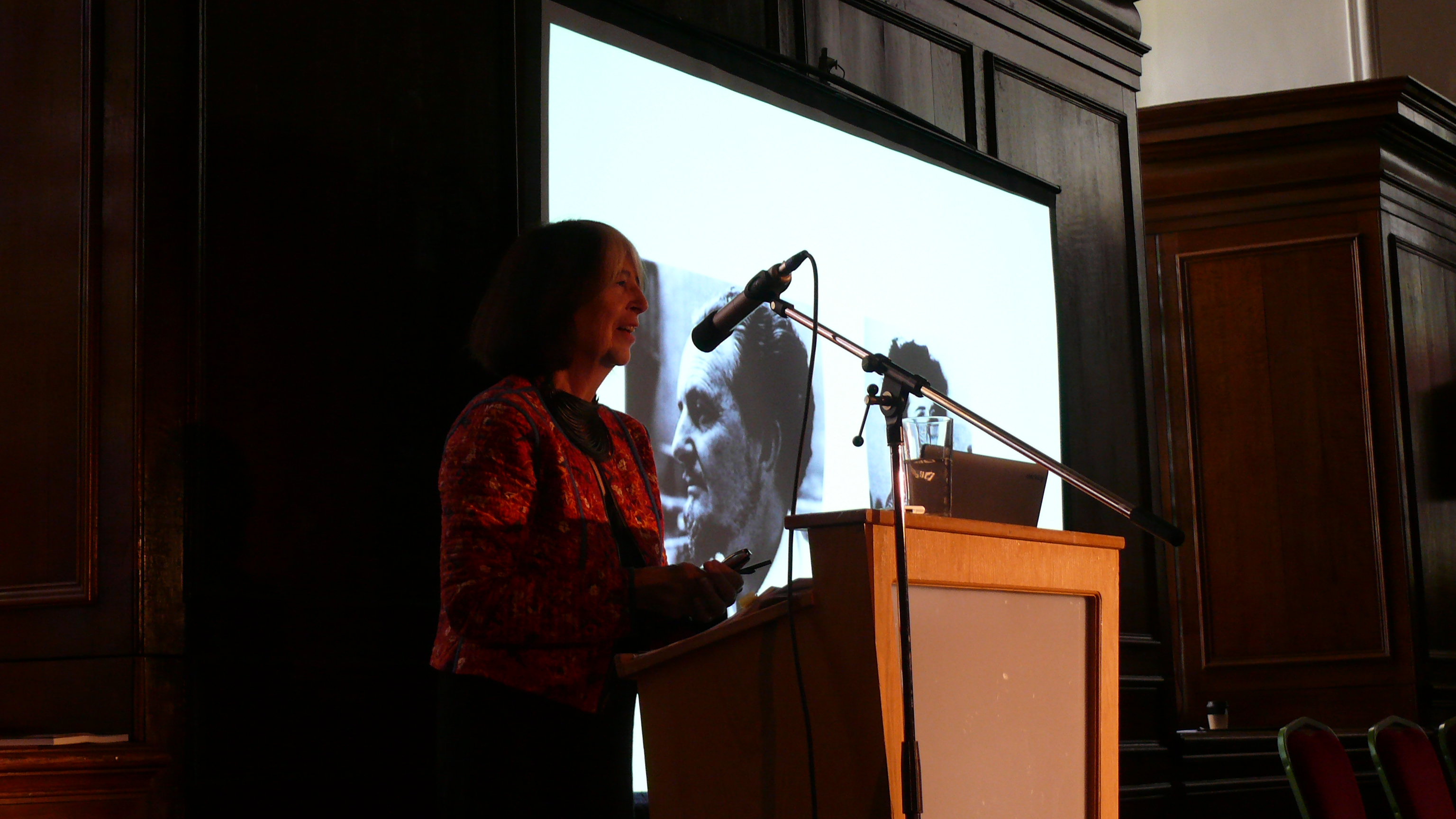

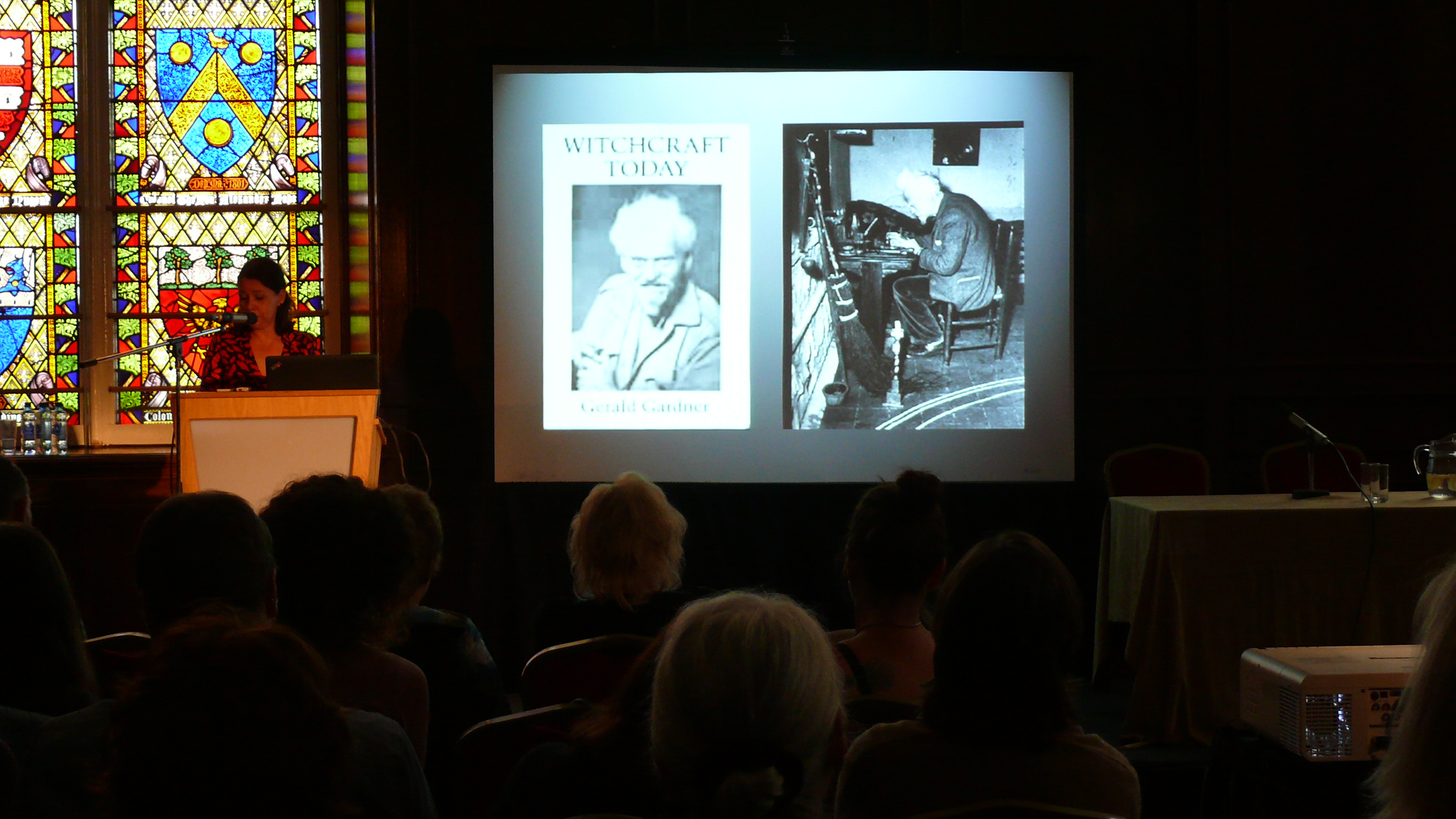

As well as the exhibition guide, we wanted to give the public a further insight into the creation of the exhibition by producing a video of artists Fiona Hallinan and Oisín Byrne speaking about their work with Rachael Thomas introducing the show. Everyone was a bit nervous before filming began, but once the conversation started some interesting and quite poignant moments were captured. You can watch the video on our YouTube page here.

It was a fun and busy opening night and Reopening Weekend, where lots of visitors were overheard chatting positively about the In the Line of Beauty exhibition. Even the quirky limited edition made especially for the exhibition by Sam Keogh sold out!

It was a busy year for IMMA in the lead up to the Reopening, and it was fantastic to experience the buzz and celebratory mood of the opening night.

-PM

Poi Marr, Exhibitions