In anticipation of the our upcoming International Symposium on Eileen Gray, here is a taster from Peter Adam who is opening our Symposium on Tuesday evening. Adam is a British filmmaker and author. Born in Germany, his work includes Eileen Gray: Her Life and Work, Outlines : David Hockney and Art of the Third Reich.

‘Looking back at the many different phases of her work one discovers a singular mind, which coloured everything she created. Her contribution to twentieth century architecture is in her refreshing thoughts and un-dogmatic approach to the quality of living. She fought many battles most of all with herself. She did not look for fame or medals; another kind of dream inhabited her outlook on things and man. She felt deeply the spirit of things and objects, reflecting and perfecting them until a house, chair or a table became the friend of man.’

-Peter Adam

International Symposium: Eileen Gray – Tuesday 13 May – Wednesday 14 May 2014

For Tickets, book here.

Sheela Gowda Talks on Soundcloud

In April, we held two talks with curators and artist of the Sheela Gowda exhibition. If you didn’t get a chance to attend, have a listen here.

04 Apr 2014

Prelude Talk | Grant Watson

As a prelude to the exhibition opening of Sheela Gowda Open Eye Policy; Grant Watson (curator, writer) discusses his curatorial interests on the various contexts that inform Indian contemporary art, and explores the cultural, social and political fabric that surrounds a reading of Gowda’s work.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/146067042″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

05 Apr 2014

In Conversation with Sheela Gowda

Sheela Gowda (artist) discusses with exhibition co-curators Annie Fletcher (Curator Exhibitions, Van Abbe museum Eindhoven) and Grant Watson (curator, writer and Senior Curator and Research Associate, Iniva London), her artistic concepts and methodologies and reflects on their shared experiences of developing this retrospective exhibition for its various touring venues.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/143680963″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Light Rhythms: An Exhibition for Families

In anticipation of our Spring Opening this Saturday, here’s what’s happened so far to give you a taster for this weekend!

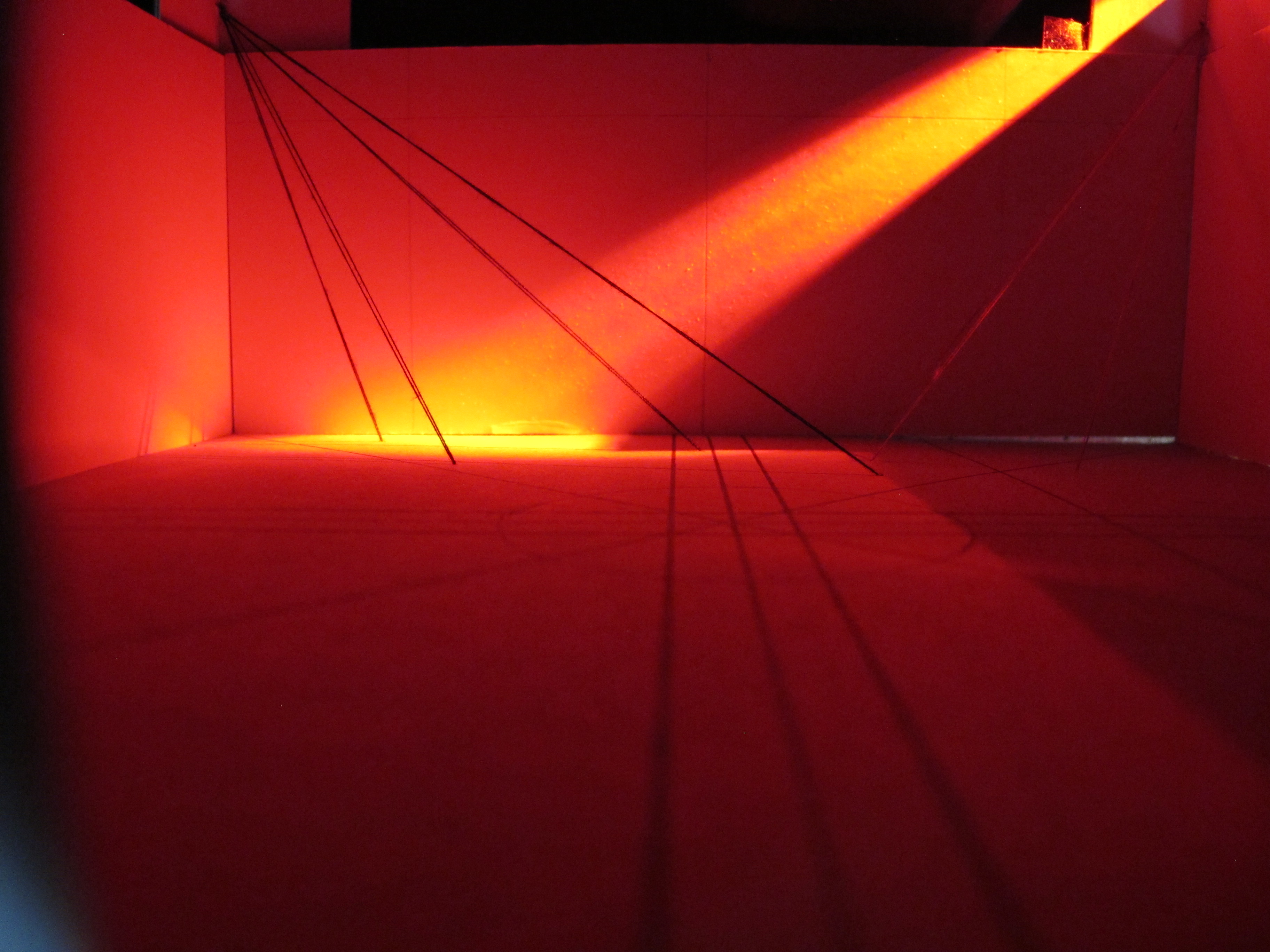

Following on from the success of our Action all Areas exhibition for families, which marked our reopening last October, I was asked to curate an exhibition for families that responded to, and facilitated an engagement with, concurrent exhibitions Patrick Scott: Image Space Light, Are jee bee? Haroon Mirza and Line Writing by Vong Phaophanit. When I began to look at these exhibitions an overlapping theme began to emerge, which was how we experience space through light, colour, line and sound.

The exhibition is a mixture of artworks from the Collection, Dorothy Cross’s Ghost Ship and Patrick Hughes’s ‘Present’ Rainbow, and artworks on loan like Here beside you in this room by Liam O’Callaghan and Colophon by Gavin Murphy. Alongside these are IMMA commissions and interactive works like Compositions 1-36 (2010) by Karl Burke and Russell Hart and Rainbow in the palm of my hand (2014) by Fionnuala Conway and Mark Linnane .

An interactive wall of LED rope lighting that invites participants to create their own installation and a room where children (and adults) can influence what colour they are immersed in, both reference the work of Haroon and Vong and aim to give participants the opportunity to play around with space and light – like an artist would.

Another element of the Light Rhythms exhibition is a series of drop in artist interventions that leave traces behind. So far, we have had:

Painting with light with Fionnuala Conway

Creating a collage of voice recordings around IMMA with Sven Anderson

Wrapping the space to the sounds of the Amazon with Slavek Kwi

And so far in our Explorer programme every Sunday from 2 – 4pm we have; taken over the space with lines, created abstract drawings in response to sound, and adapted the space with light projections and colour!

Our next artist intervention in the Light Rhythms exhibition will be Saturday 5 April from 12pm with Karl Burke – where visitors will be invited to stop and listen, and to take part in a collaborative sound installation. This is part of our spring launch party, which also includes a drop-in DJ workshop with DJ Simon Conway for children aged 7+ (and parents) and an interactive sculptural installation in our courtyard called Making the Connection by Julian Wild.

The Light Rhythms exhibition will close mid-week from the 7 April for re-installation and will be open over the Easter school holidays.

By Katy Fitzpatrick, Light Rhythms curator

Images Katy Fitzpatrick and Senija Topcic.

Sheela Gowda: Open Eye Policy by Grant Watson from Lunds Konsthall

In anticipation of the Sheela Gowda exhibition opening at IMMA this Saturday 5th April, Lunds konsthall have kindly given us permission to share their publication by exhibition co-curator Grant Watson.

Lunds exhibiton guide by Grant Watson (pdf with images)

We are very happy to be able to show Open Eye

Policy, a highly topical exhibition by prominent and

internationally renowned Indian artist Sheela Gowda.

This is the first time the Swedish public has the

opportunity to see a comprehensive presentation of her

work. The exhibition is produced by Van Abbemuseum

in Eindhoven, the Netherlands, and specially adapted

to fit Lunds konsthall in the best possible way.

Gowda was born in 1957 in Bhadravati in

the south Indian state of Karnataka. She lives in

Karnataka’s largest city, Bangalore, perhaps best

known for its booming IT industry. She graduated

from art academies in both India and England, and

therefore has an insider’s view of both European and

Indian art.

Gowda emerged in the 1980s as a figurative

painter, but her motifs underwent a gradual process

of abstraction until the paintings became objects in

three-dimensional space: sculptures and installations.

Gowda has developed a characteristic approach that

balances abstract composition and theatrical staging.

Materials are of crucial importance in her

work. Often sourced from her immediate surroundings,

they provide important insight into her process of

thinking-through-making. Formal concerns – such as

understated figuration and unexpected juxtapositions

of elements – also indicate possible readings of Gowda’s work, as do her titles.

Through her practice she articulates her

view on the times we live in, from the vantage point

of someone familiar with both Indian and Western

culture. Gowda’s approach is characterised by healthy

scepticism towards generalising and universalising

about the situation of others. In her work the insistence

on speaking from her own perspective, about a

reality she is in the position to observe and analyse, is

elevated to poignant social critique. This, in itself, is a

fundamentally political stance.

First of all, I very warmly thank Sheela

Gowda for her strong commitment to this exhibition,

and for agreeing to show Open Eye Policy at Lunds

konsthall. I also thank the guest curator, Grant

Watson, for our excellent collaboration, as well as

curator Annie Fletcher and director Charles Esche

at Van Abbemuseum, who have made it possible for

Lunds konsthall to collaborate on this exhibition,

which will also travel to the Centre international d’art

et du paysageIle de Vassivière in Beaumont-du-Lac,

France.

Last but not least I wish to thank all the

lenders: Sheela Gowda herself, Arani and Mita Bose,

Thomas Erben, Amrita Jhaveri, Sunitha Kumar

Emmet, Karin Miller Lewis and Ashish Rajadhyaksha.

Without their generosity, this exhibition and its tour

would never have happened.

Åsa Nacking

Director, Lunds konsthall

Sheela Gowda Open Eye Policy

Sheela Gowda is well known for her sculptural works of

elegance and scale, which often adapt found materials.

Since the early 1990s she has shown in museums and

biennials around the world, but only now has her

practice been brought together in an exhibition that

constitutes something like a retrospective. Open Eye

Policy provides the opportunity to see the diversity of

her practice, but also the consistency that comes from

interests sustained over several decades. The range is

wide in terms of scale, medium and approach, but the

individual works are nevertheless readable as part of one

oeuvre. The exhibition demonstrates Gowda’s extensive

back catalogue and the lines running through it, such as

the ongoing investigation of materials, the appropriation

of found elements and the frequent engagement with

abstraction and issues of representation.

At Lunds konsthall Gowda’s work is shown in

a relationship to Klas Anshelm’s distinctive modernist

architecture, which lends itself particularly well to

her installations. Many of these can be reconfigured

differently according to the space in which they are

shown, and here advantage has been taken of the

gallery’s height and the variety of different views that

the building affords. This approach goes against the

grain of a strictly chronological display, so here works

from a period of twenty years – early studies, smaller

sculptures, large-scale installations and works on paper

– are seen in combination.

Painting

Gowda is perhaps mostly known as a sculptor but

originally trained as a painter, first at the Ken School

in Bangalore (where she learnt the skills of figuration,

which can be seen in her watercolours), then at the

Fine Art Faculty of Baroda and at Kala Bhavan,

Shantiniketan, and finally at the Royal College of Art

in London.

Although Gowda only spent a short period

in Baroda (in 1979–1980), her encounter there with

the eminent artist and teacher K G Subramanyan

was a formative one. He had helped establish what

was dubbed the ‘School of Baroda’, known for its

figurative narration, but for Gowda he opened a

door to abstraction. She explains how, in tutorials,

Subramanyan refused to let her take a storytelling

approach and instead directed her towards formal

concerns and using a wide range of materials and

visual stimuli. His principle advice was that artists

should seek to synthesise many different ‘aspects of

contemporary experience, tradition, the west, the

historical reality and the phenomenal world’ – words

that clearly resonated with Gowda and continue to

inform her today.

At the beginning of the 1990s Gowda shifted

her paintings towards abstraction, initially by giving

equal weight to the spaces between the figures in

them and the figures themselves. This led to the

simplification and reduction of the figurative element,

until it virtually disappeared. Her move towards

abstraction took place gradually and spontaneously,

prompted by developments on the picture surface,

but it was also linked chronologically to a shift from

painting to sculpture.

Cow Dung

What enabled this was her discovery of cow dung as

a medium. She first used it in her paintings and then

as a material in its own right for sculptures. These

were shown for the first time in the form of cow dung

pats piled on the floor as part of an installation at

Gallery Chemould in Bombay in 1992. This use of

cow dung defined Gowda’s practice for a period in

the early 1990s and also suggested the potential of

materials in general to function not only according to

their sensorial qualities (colour, texture and form), but

also in terms of the meanings associated with them.

Importantly, she considered the focus on materials

as a way to address her immediate environment –

including India’s cultural and political realities.

Gowda selects materials taken from her

surroundings, often noticed first for their abstract

qualities and utility rather than their connotations.

This initial selection is followed by a more protracted

period when the potential of the material is

scrutinised, both physically and conceptually. What

will the material do? How can it be transformed,

burned, woven, flattened, diluted? What structures

does it make possible? How will the viewer interpret

it and how will this be influenced by the artist’s

decisions? Gowda proceeds through trial and error,

a kind of ‘thinking through making’ in which her

intuitions and preconceptions are tested in the

studio and judged according to criteria that are

both conceptual and aesthetic. Materials and

concepts become interlaced to produce an aesthetic

vocabulary specific to her. Once a material has been

tried out it will often become part of her repertoire

and used in different contexts.

Cow dung was something already culturally

significant, but it was also a surprisingly flexible

and visually pleasing material to make art with.

Initially it appeared in diluted form, used as a wash

in Gowda’s paintings to produce a textured and

at times raised coating, suggestive of the very act

of smearing excrement onto their surfaces. One

example is Untitled (1992), a work on paper. It is

predominantly abstract, but in one corner we notice

a tight composition of figurative elements including

an Asian cow (Zebu), a woman collecting dung and

a pair of sandaled feet. This grouping references the

physical presence of the cow in Indian village life

and the crucial role it plays in the agrarian economy.

The cow’s status is protected in Hindu scriptures; it

provides milk as well as dung, which can be used both

as fuel and as an antiseptic. Gowda’s drawing also

suggests her own proximity to this village economy.

The theme is developed more fully in My

Private Gallery (1998–1999), a work composed

of two panels joined at a right angle and placed

in the corner of the room to produce an enclosed

space, within which Gowda ping a series of small

watercolours. The exterior surface of the panels

are made from cheap marbled plastic laminate,

reminiscent of the mass-produced materials used

in the construction of urbanised India, while the

interior is coated with a layer of dung, overlaid with

miniature cow pats similar to those seen on walls

throughout rural India. The watercolours depict faces

of people from the district where Gowda lives (at that

time the indefinite border of a metropolis expanding

at breakneck speed), many of them migrants who

maintain their own rural ways in the city. There are

also scenes from a car window, showing this urban

development as a hectic work in progress. A stack

of cow dung bricks and piles of pats nearby (similar

to those shown at Chemould in 1992) attract our

attention to the material itself. Dung is a basic

building block for the work. It is malleable and

robust, odourless, textured and organic – a constant

dull brown but at the same time patchy and varied in

its tones.

The idea of dung as a basic element is

reaffirmed by Stock (2012) where cardboard boxes

with balls of dung sit on the floor waiting to be used.

In a humorous touch, faces are coarsely scratched

onto them. In the earlier paintings dung was mixed

with pigment, and Gowda uses a similar combination

for several of her sculptures. Mortar Line (1996)

presents an arc of cow dung bricks laid out in tight

pairs on the floor with pigment squeezed into the

cracks between them, forming a curved red line. In

Gallant Hearts (1996) cow dung is compacted into

small fist-sized forms, rough and varied as stones,

which are coated red and suspended in a bunch from

a nail on the wall.

Red String

And Tell Him of My Pain (1997, here shown in a version

from 2007 titled And…) brings together several of the

elements which had been present in Gowda’s practice

up to that point. It is made using a more complex and

extensive working process than before, with multiple

threads being passed through as many needles, then

brought together and coated in red pigment and

glue, which binds them into a semi-flexible cord. The

cord is then coiled around the room – touching the

floor, walls and ceiling and making optical, sensory

and allegorical links between them. This is a bold

and elegant work that fills the space. The cord evokes

earth tones, the internal organs of the body and the

sinuous strength and flexibility of succulent creepers.

The composition in the room recalls the variegated

movements of a Jackson Pollock action painting, but

it also creates a pathway for viewers. The abstracted

figures present in Gowda’s earlier paintings have

been whittled down to a coiling dark red line, and the

spaces it demarcates become gaps that viewers can

enter and pass through.

In Breaths (2002) red string is bundled to

produce cylindrical forms of varying lengths, which

are then contained in a black muslin skin smeared with

charcoal. the innards of red string spill out from their

black casing, revealing frayed and bleeding edges.

The table, acting as support for the work, suggests the

reading that these are limbs that have been roughly

severed and laid out for inspection, although the varied

sizes of the different sections also contradict this and

indicate that the victimised material might be nonhuman

– perhaps burnt logs, the violently transformed

limbs of a tree

Tar Drums

Blanket and the Sky (2004) is the first in a series of

works for which Gowda uses tar drums bought from

workers who tarmac the roads in India. For Gowda

these metal sheets, flattened with road rollers, become

an aesthetically interesting sculptural material

that is light but strong. The surface of the sheets is

marked with lines still visible after the flattening, their

colour is steel grey and inky black with intermittent

patches of orange rust. The fact that the workers

also use the metal sheets to build temporary shelters

where they can sleep shows that the material can be

appropriated for unexpected practical purposes. The

size of the sheets determines the dimension of these

improvised workers’ dwellings. The most ambitious of

the installations made from tar drums is Kagebangara

(2001). Flattened sheets and un-flattened drums are

arranged along with tarpaulins in primary yellow

and blue that are also used on construction sites,

into a sculptural installation on the floor and walls

of the gallery. At first this appears to be an abstract

composition of volumes, surfaces and tones – drums

piled and sheets stacked, monotone blacks and

metallic greys against the brightly coloured plastic

squares. But when we move into the installation and

look at it more closely a narrative begins to emerge.

This might be a roadside encampment with a narrow

shelter behind the metal sheets stacked against the

wall and silica placed at the base of the tar drums

to suggest collected pools of water. As our spatial

relation to the work changes, we experience it as

balanced between abstract composition and theatrical

tableau – with the materials arranged so that they can

communicate both interpretations.

Wooden Chips

A recent large-scale work titled Of All People (2011)

might take viewers by surprise when seen in the

overall context of the exhibition. Unlike in her other

installations, which are pared down to include just one

or two elements, Gowda uses several quite different

materials in combination. She works with different

scales simultaneously and uses brilliant colours.

She began by selecting the small wooden

chips that may appear to be random and

unidentifiable fragments but actually have features

indicating that they should be seen as human figures.

Used in India as votive objects, these chips are

individually carved, but over time the craftsmen have

began to produce them so rapidly that the human

features have become almost unrecognisable. When

they are held up and scrutinised closely their humanity

comes into focus, but left in a pile they dissolve into a

featureless mass, somewhere between abstraction and

figuration, between formed and unformed matter.

To play with this ambiguity Gowda has chosen

to make a ‘stage’ for the little figures, showing them

in an environment that includes a table turned upside

down, door frames (some standing, others broken open

and suspended), wooden columns and window frames

hung from the wall, complete with shutters and metal

grills. Unusually for Gowda, this work includes vivid

colours similar to those found in Indian vernacular

architecture and domestic interiors – bright pink,

emerald green, golden yellow, turquoise blue.

Yet the framing devices do not become too

significant in themselves. The door is a door and

the window a window, but they can also be read

as geometric shapes arranged on the ground or

suspended in the air. Rather than relating this work to

architecture and domestic space, which the doors and

windows and tables would suggest, Gowda describes

it as an immersive landscape. This environment

complicates our interpretation of the little wooden

figures. To be able to understand the work we must

walk through it and view it from a variety of angles

and distances.

Works on Paper

A noticeable development in recent years has been

the increased visibility of painting within Gowda’s

practice. Painting has always been there, of course,

although the shift to sculpture – incidentally

something that Gowda shared with several other

significant Indian artists in the early 1990s – might

have prevented us from seeing that.

Visiting her studio in 2002, I was surprised

when she showed me a series of watercolours

copied from newspapers: photographs of sportsmen

abstracted to silhouettes, indistinct because overlaid

with thin washes of paint, that gave the impression of

rioters running through clouds of smoke or tear gas.

These small works on paper eventually found their

way into a sculptural installation, but increasingly

Gowda now shows her paintings independently.

They are almost always based on images taken from

the media, asking us to question what we see and

what we think we see and highlighting the process of

reproduction and the artist’s role in it. Gowda herself

questions this role and her relationship to the material.

What does it mean to look at images of violence?

What might be an appropriate response? What

are the possibilities for action, for empathy or even

comprehension?

Sanjay Narrates (2004), for instance, takes a

tragic incident, a scene of violence from Palestine, and

breaks it down into 14 sections, which are shown in a

line on the wall. Each is a meticulously painted but

abstracted fragment of the whole, depicting a hand,

a face in pain, feet, arms clenched, a blurred section

of background. Gowda has scanned the image with

care and produced a visual document that is less

complete, and ultimately less legible, than the original

newspaper clipping. Yet the effort of reproduction itself

seems to attempt to understand the gravity of this

scene.

Two sets of works on paper underline

the status of images as ambiguous documents.

Fakes (2008) features three framed inkjet prints of

banknotes, of which some sections have been enlarged

and painted over by Gowda. The original bank notes

are themselves small pieces of paper with images

and patterns printed on them to denote monetary

value, and their reproduction partly mimics the act

of forgery. The enlarged figures, cross-hatching and

meticulously copied scribbled pen marks highlight

details that are there to deter precisely that, but they

also begin to reference the language of art.

Crime Fiction (2008) is a set of two images,

one of a butterfly wing seen through a microscope

and the other of a lone woman hurling a rock at what

looks like a police barricade. The first image is an

example of how nature plays with representations

and tricks the eye, as the moth is one of a kind

whose wings imitate the features of an owl in order

to deter predators. The second image comes without

explanation, but we almost instinctively believe we

understand what is happening and interpret the

woman’s gesture as something brave and futile. But

Gowda has complicated our reception of these images

by attaching little beads to their pixellated surfaces.

At an almost subliminal level, this points at their

physical presence in the gallery and at her own acts of

selecting, staging and post-production.

Heartland (2011) is an enlarged photographic

clipping from a newspaper, showing a suspected

tribal insurgent who has just been captured by the

Indian military. The title refers to the vast tracts of

Central and Eastern India said to be controlled by

Maoist guerillas, the so-called Naxalites. The image

concentrates our attention on the central figure. He

appears in sharp relief while his captors sink into

the background. His face is set in an indescribable

expression, his half-naked body with a curious black

collar around the neck seems defenseless against

army brutality. But he is given a certain defiant

agency, because while in the original image his gaze

is set at an angle, here Gowda has doctored the

right eye so that it implicates us by staring out of the

picture, directly at us.

Protest My Son (2011) features members

of the Indian ‘tribe’ Hakki Pikki who appear to be

showing off for the camera. The found image has the

spectacular appeal of advertising but is at the same

time riddled with contradictions. It is blown up to

wall size, but on a smaller inserted repeat Gowda has

transformed the figures into anthropological types,

giving some of them ‘Native American’ headgear.

A sarcastic comment, perhaps, on our appetite

for the exotic and our inability to empathise with

marginalised peoples. Meanwhile, a real-life tourist

souvenir (a somewhat threatening fetish object of

fake animal claws suspended on a string) hangs from

the larger image and ‘brings it to life’ as if it were a

diorama in an anthropology museum. Gowda calls

this her ‘active abuse’ of the original image, and it

forcefully brings out the problem of representation

that is implicit in it.

Best Cuttings (2008) neatly connects found

material from newspapers with Gowda’s sculptural

installations. A fictional newspaper called the Chronic

Chronicle, put together by the artist and her husband

Christoph Storz from existing articles about Indian

national pride and Hindu fundamentalist politics,

becomes the surface for a series of dress-making

patterns outlined in red. This reflects how tailors recycle

newsprint in India and suggests the potential for three

dimensions on a flat surface. At the same time it echoes

the red chords of Gowda’s sculptural installations,

which in this exhibition are positioned nearby.

Open Eye Policy

Seen together, the works on paper and the sculptural

installations help viewers to better understand

Gowda’s practice as a whole, and the relation between

its different parts. The juxtaposition also nuances

the straightforward focus on abstraction in Gowda’s

work and the often-made claim that it is influenced by

minimalism.

The exhibition places more importance on

Gowda’s methodology, emphasising her appropriation

and transformation of found elements and their

staging in the gallery as the result of a series of

material and conceptual moves. The works on

paper help to understand her process of borrowing,

modification and presentation, as well as her interest

in allowing materials to cross the threshold between

everyday life and the space of art.

Rather than thinking of Gowda’s art as

minimalist, we should reflect on her own description

of her working method as one in which things are

reduced and ‘trimmed’ down to a limited range

of attributes. Yet even transformed and pared

down in this way, her chosen materials bring

with them a residual presence of the world, which

becomes apparent to us in a number of ways. This

can be because of the title of the work, because

of our own associations or intuitions, because of

an accompanying text, or because of the work’s

composition in space.

While Gowda takes great care to sidestep the

pitfalls of representation, or any attempt to describe a

whole social scene. By paring her work down to a few

elements, she nevertheless invokes a range of human

experience. She is clear about her role in this process,

as an artist who takes up materials for their formal

qualities. At the same time she has what she calls an

‘open eye policy’, acknowledging rather than negating

the source of these materials and the economies within

which they once circulated. Used as a title for the

exhibition, Open Eye Policy also becomes an invitation

for us to look more closely, something perhaps desired

by all artists, but which here is imperative.

Grant Watson

Curator of the Exhibition

Vong Phaophanit on Line Writing (1994) at IMMA

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eXySqRamV2Q?list=UUAfvQi5gJPMnFZ4k2ZelLSg]

Are jee be? Haroon Mirza

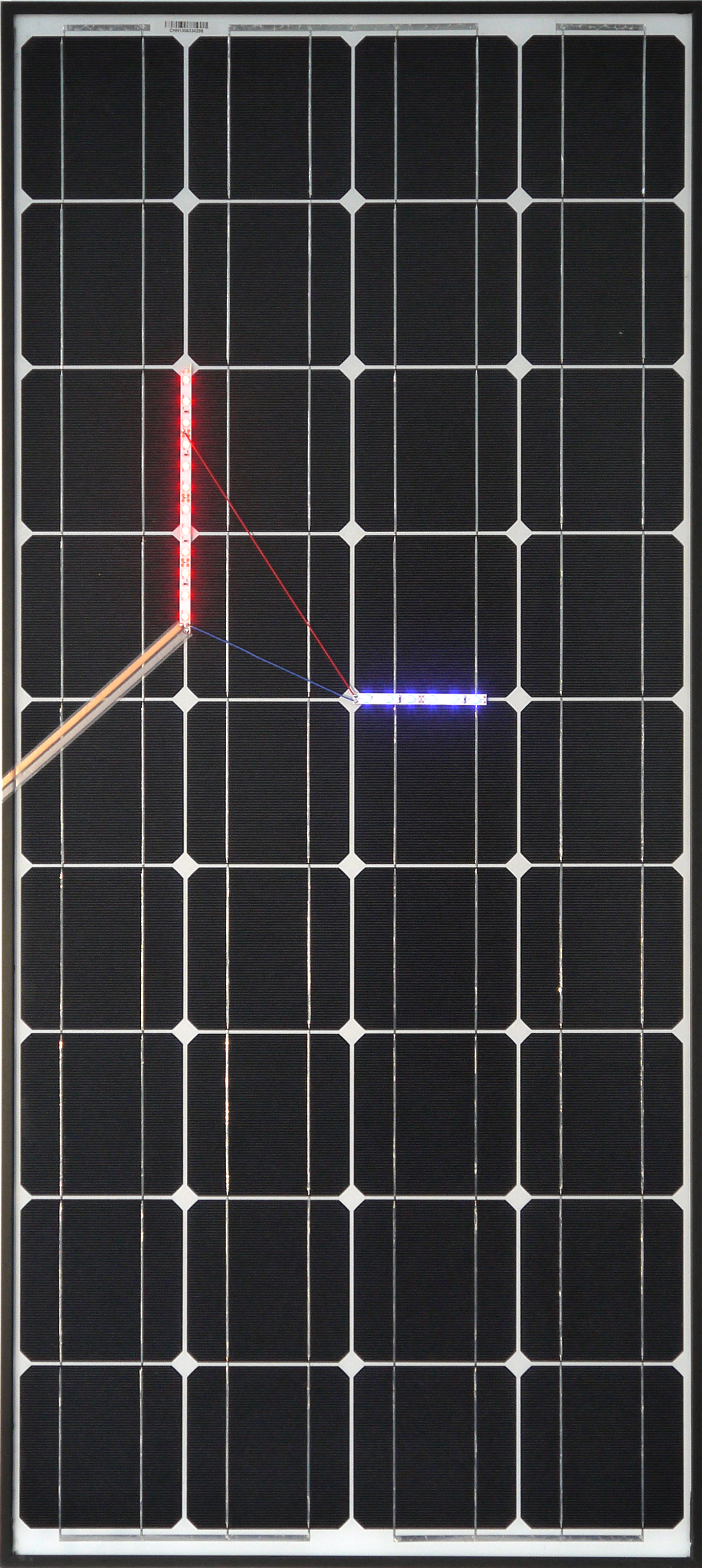

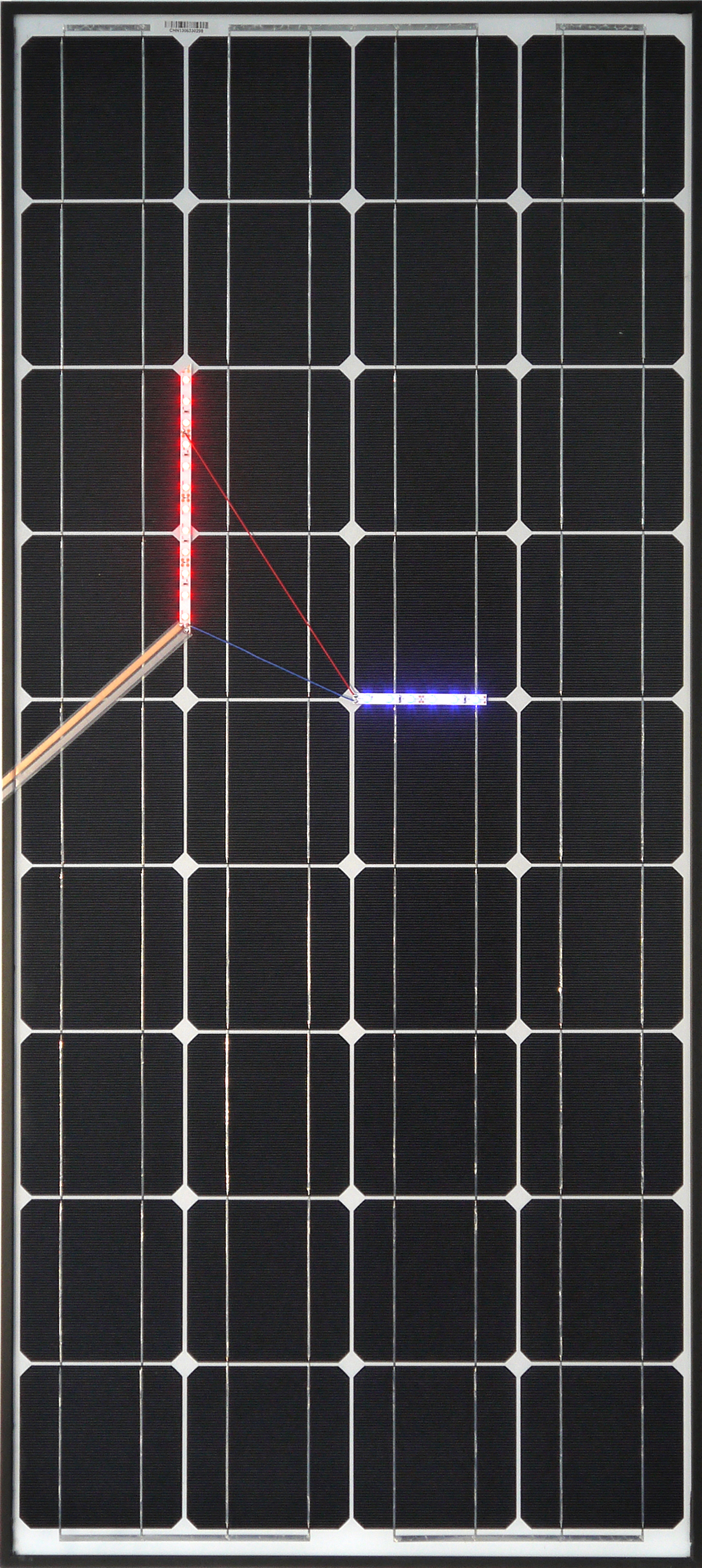

Haroon Mirza’s new project Are jee be? has been in development for almost a year now, so it is rewarding to finally see it presented at the Museum. The end result is a carefully conceived site-specific response to the very particular architecture of IMMA’s site at the Royal Hospital Kilmainham. The title of the exhibition is a word play on the RGB (Red, Green, Blue) additive primary colour model, and these three elements are important in the framework of the installation.

The corridor features a sequence of Solar Powered LED Circuit Compositions; a new departure in Mirza’s practice. These panels are controlled and activated by the amount of light in the space, from both natural and artificial sources. These works, a series of sundials of sorts, will illuminate according to the time of day and may dim due to obstructions from viewers as they move in front of the light source.

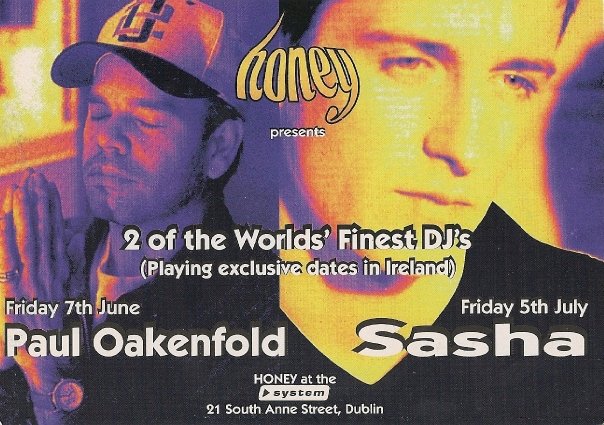

The four adjoining rooms leading from the corridor feature a new multi-sensorial installation The System. Titled after the 1990s Dublin nightclub ‘System’ originally on South Anne Street. The club was key in the history of dance music in this city and a music genre that has been a key influence on Mirza’s work. The club was only in existence for a few years, but made a mark in the memories of its patrons. You can listen to an original recording of a DJ Set from ‘System’ here.

IMMA has also organised a 90s club night on April 5th where Mirza is playing music (on original vinyl) from the era along with other sets by DJs Donal Dineen and Adrian Dunlea. Mirza has had an ongoing interest in the intersection between the visual arts and music. In our new publication accompanying the exhibition Christoph Cox connects Mirza’s practice to the history of electronic music.

We worked with PONY on the design and production of the publication. I asked lead designer, Niall Sweeney, to contribute some words about their approach:

“We wanted the book to have some of the sensorial experience of Mirza’s works. It is printed on high white paper (paper treated with a UV agent), that has a specific textural feel. Most of the book is printed in high density black ink, with a number of images deliberately revealing their low resolution pixels, and then the colour section uses fluorescent component replacement. This is where we replace the M and Y inks of standard full colour printing inks (CMYK: Cyan, Magenta, Yellow, Black) with fluorescent Magenta and Yellow. This makes the images glow and shifts the colour gamut range of what the eye can see in a printed image. It can have somewhat unpredictable, but always pleasurable, results. As a final detail, the book is sewn using red, green and blue threads – the colours that bind us all together in the visible, technological world.”

For this exhibition, Mirza has taken the interpretation/introduction area of IMMA’s preceding Eileen Gray exhibition as a ‘readymade’ for his project. Incorporating museological modes of display (including a timeline of Gray’s life, vitrines and artwork labels), he creates a fusion and remix between both exhibitions. My own text in the publication expands on the ‘duet’ between Mirza and Gray. Mirza is also about to complete a project entitled The Light Hours in Le Corbusier’s (with whom Gray had a legendary and turbulent affiliation) Villa Savoye at Poissy in the outskirts of Paris, so the opportunity for Mirza to feature elements of the Gray exhibition for his own purposes sets up an interesting counterpoint in which to experience his own innovative work practice.

Séamus McCormack, Exhibitions

On Location at IMMA: The IADT First Years

First-year students from the Institute of Art, Design and Technology (IADT) Dun Laoghaire, discuss their experience of being based in IMMA

The B.A (Hons) ART (previously known as Visual Arts Practice) course within the Faculty of Film, Art and Creative Technologies at IADT is a four year programme designed to guide students into developing a practice relevant to the many opportunities existing for artists as well as help them understand the challenges of working in the visually and critically sophisticated landscape of contemporary art.

In the first year of the course, students are given a range of key projects dealing with the application and implementation of research strategies and methodologies. These projects engage learning through analysis, problem solving and research development.

One of the main assignments in the first year is a 12 week project based in the Irish Museum of Modern Art’s artist studios. Called Base1Art, students get to use IMMA as a site-specific location for their individual projects. Supported by IMMA’s Education Department, the programme is facilitated by Lisa Moran. She and the Museum have been an integral part of the first year’s experience since 2009.

During the first six weeks of the programme, in the lead-up to the midpoint of the project, the students participate in key events such as staff talks and access to the programmes at IMMA such as the Eileen Gray and the In the Line of Beauty exhibitions, a talk from Luís Pedro from the Irish Architecture Foundation as well as the Collection exhibition One Foot in the Real World.

IMMA and OPW staff like Mary Condon the Royal Hospital Gardener introduces the students to the RHK site with a walk of detailed historical information, and Janice Hough, the Artist Residency Programme Coordinator, gives the students an overview of IMMA’s artist programmes. The students enjoy a variety of exhibitions in IMMA, currently Are jee be? Haroon Mirza, Patrick Scott: Image Space Light and the family exhibition Light Rhythms.

The project has just hit its six-week point, and the students have presented to their peers as well as some of the IMMA staff. This gives the students the opportunity to reflect on their diverse research they’ve undertaken and plan and finalise the outcome culminating in their end of year exhibition.

We have asked some of the students to share their experience so far working on site in IMMA showing examples of their current research.

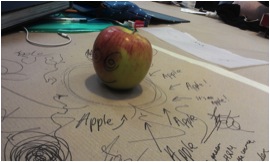

Lorcan Mc Geough, First Year, B.A (Hons) ART, IADT:

My project is about sound and space. Influenced by the Artists Olafur Eliasson and Zimoun, I’ve striven to understand sound, how it moves throughout a space and how humans hear and react to sound – the physical properties of sound, how to amplify and direct that through physical means. A sound based atmosphere is what I hope to create, to have people react on an individual level to this very instinctive sense. This project has taught me a lot so far: How to deal with site-specific work, the considerations and constant rethinking and reworking of ideas to cope with the available space, how to adjust and how to draw the most out of what you have started with. The site at IMMA is great, and being able to show yourself off to the staff of a major institution is also a great opportunity.

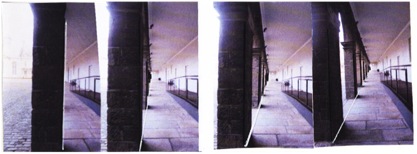

Lea Blanchard, First Year, B.A (Hons) ART, IADT:

I’m a first year student of Visual Arts Practice at IADT. As someone who lost two years of practicing art due to a panicked, last-minute decision to go to UCD instead of IADT (and then thankfully finding an opportunity to change over to my dream course), the idea of having to do something as big and public as a site-specific piece in IMMA was very daunting. However, with baby steps and curiosity being fed by welcoming and friendly staff and the location itself being breathtakingly perfect for an aspiring artist, I now feel a huge sense of excitement for this project.

One of the big things that caught my eye about IMMA are the shadows. I like the solid aspect of a shadow; how depending on the angle of the light, it completely distorts the original shape of the shadow-caster and becomes an image itself. My plan is to try and bring attention to specific shadows throughout IMMA, either making a sculptural piece or an installation that would divert the public’s attention from the caster to the strange and solid shape of the shadow.

Megan Robinson, First Year, B.A (Hons) ART, IADT:

My time is IMMA has been most enjoyable and I’ve earned a lot in my time here. Site specific work has taken me out of my comfort zone and forced me to look at the surroundings in a very different way. IMMA has provided lots of inspiration and what has interested me most is how the architectural structures breaks up light and casts harsh shadows and how space is defined by shadow.

I began observing the light in the courtyard and from that i have learned to explore light and do a range of experiments to try alter, control and intercept light. It was great having lots of new and interesting exhibitions here on site which always provided some inspiration when needed. I especially enjoyed the Patrick Scott: Image Space Light and the Sol Lewitt prints up in the main gallery. I have learned so much in my time here in IMMA.

Amanda Connolly, First Year, B.A (Hons) ART, IADT:

I have thoroughly enjoyed my time working in IMMA. The scenery and the work around the galleries are very inspirational and I was instantly motivated to start working. Practicing with site specific work has been something very different to other work I have done but has proved enjoyable and an effective way of working so far.

Carolina Cantor, First Year, B.A (Hons) ART, IADT:

My site-specific project was based on light, time and shadows. I was fascinated by the marks left on the structure in the courtyard and how it was in constant motion. It was never going to be in the same place more than once a day. I liked the idea that it was something that would only happen under certain conditions (sunlight). The two most important elements are time and light.

The location itself is prodigious and is an enormous opportunity for a 1ST year student to work where many well known artists have worked. The IMMA staff members have been more than welcoming and have been very accommodating in letting us make use of their studios, for which I’m very thankful.

Emma McKeagney, First Year, B.A (Hons) ART, IADT:

The move up to IMMA is something we had been leading up to all year. After every project, as well as feedback from our tutors came the whisperings of “IMMA.” After a term of structured projects with clear outcomes, the thought of a self directed project, with no restrictions except to be site specific, seemed daunting.

It has been challenging, but IMMA really hasn’t fallen short as a source of inspiration. The grounds, the building, the gardens – were all sources of fresh, albeit often freezing, air and a new perspective. Although most people have based there projects around these aspects of IMMA, the various exhibitions while we have been on location have moulded our projects considerably.

Our first few days consisted of walking the grounds and taking pictures of what interested us. These first photos became the building blocks of our research, and slowly, interrupted at times by mild cases of artists’ block, but our projects began to develop.

From the IMMA Archives: Patrick Scott Interview, 1993

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/139365595″ params=”color=ff5500&auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_artwork=true” width=”100%” height=”166″ iframe=”true” /]

Christina Kennedy on the Patrick Scott Exhibition

Without making a song and dance, and for all the sweet domesticity of a cat haunted life, and a modest sweetness of nature, Scott has been an artist of huge ambition and major achievement: it’s just that he hasn’t told anyone about it.”

-Mel Gooding, November 2013

……………………………………………………………………………………….

When I first sat down to write a blog for the exhibition Patrick Scott: Image Space Light, I had a different plan in mind. Then sadly Patrick passed away on Friday the 14th February, the day before the opening of his exhibition at IMMA. It has been a privilege to curate the exhibition Patrick Scott: Image Space Light, which is currently running at IMMA and VISUAL Centre for Contemporary Art Carlow. The exhibition now performs the double role of being a major tribute to the extent and calibre of Scott’s work as an artist, designer and architect and the esteem in which he is held. By engaging with his work, there is an immediate and poignant connection with the talent and life of a wonderful individual.

One of the defining aspects of working on this exhibition was the need to curate it across two venues and as a single exhibition. As well as enabling a much larger exhibition, the dual aspect provided unique and exciting challenges as the two venues could not be more different. At IMMA the Garden Galleries consist of the intimately scaled 18th century rooms of the former Deputy Master’s House of the Royal Hospital Kilmainham. Diametrically different, VISUAL is a purpose-built multi-disciplinary art space whose exhibition galleries comprise a monumental main space whose floor plan is 29 x 16m with a ceiling height of 11m as well as three other expansive spaces. The characteristics of each gave rise to distinct curatorial decisions.

From the start it was clear that the first half or Part I of the artist’s career would best be appreciated in the intimate spaces of the Garden Galleries at IMMA. Its first floor rooms are ideal for experiencing the smaller scaled ‘White Stag’ related paintings of stylized birds and fish in schematic landscapes and the still-lifes, wire and scaffolding motifs that Scott abstracted from everyday life during the 1950s. These rooms also provide a focused setting for the reiteration of part of Scott’s representation of Ireland at the Venice Biennale in 1960 (IMAGE) twigs and books.

The paradoxically higher-ceilinged basement gallery at once provides qualities of breadth and visual compression that in this case intensify the luminescent evocations that are the bog paintings and the kinetic energy of the Device series. Key early Gold Paintings and the unique Rosc related works provide contemplation and drama in equal measure in the naturally lit, ground floor rooms.

VISUAL on the other hand facilitates Scott’s larger scale works, many of which were produced in the latter half of his career such as the tapestries. Installed in the studio gallery, they are richly coloured abstract designs derived from the artist’s thumbprint and were mainly woven at Aubusson (France) and with V’Soske Joyce (Galway). The largest were created for the minimalist interiors of corporate modernist buildings from the 1960s onwards. In the main space is the 20ft canvas Kite! accompanied by a signature representation of Gold Paintings from the late 1960s to 2007 as well as examples of Scott’s furniture including folding screens and Tables for Meditation.

In complete contrast with the domestic-scaled spaces of the Garden Galleries, where the largest of the Device paintings barely made it down the narrow stairs to the basement gallery (under the watchful eye of Hugh Lane’s conservator Jane McFee), the expansiveness and soaring height of the spaces at VISUAL necessitated a platform lift with several crew to install Kite! and Eroica, seen here slowly being unfurled down the wall

When doing research for the show last year, I had numerous brief meetings with Pat, as much as he could manage. We talked about aspects of his practice, in so far as Pat would ever give much away about his work. “He doesn’t exactly sell himself,” was how his good friend and critic the late Dorothy Walker once put it.

We discussed in whose collections certain works were located, ideas for the installation and what works might be located at IMMA and those for VISUAL. Pat knew the IMMA spaces well and had visited VISUAL on the occasion of Michael Warren’s exhibition there in 2010.

As curator, an aspect I wished to bring to this latest consideration of Scott’s work was to include a direct response by a younger generation artist with an empathy towards Scott’s work and also towards architecture. I invited Corban Walker to guest curate a selection of works by Scott for the Link Gallery, to write a text for the catalogue and to make a work in response for the window area of the Link Gallery. Corban grew up among Pat Scott works which hung in the home of his parents, Dorothy and Robin Walker and his friendship with Scott contributed to his own artistic direction.

I had previously worked with Pat on his retrospective exhibition, curated by Yvonne Scott, at the Hugh Lane in 2002 (when he was a young 81). My abiding memory is of his central presence in all decisions to do with the installation, conveyed in his economical, good humoured, no fuss manner. I felt a particular obligation to convey as closely as possible to him how this exhibition was evolving.

I was thrilled along the way when Pat offered me the chance to go through his papers, assisted and mediated by his partner Eric Pearce. This provided an archive of correspondence relating to Pat’s life: letters from friends, colleagues, relating to commissions, bills, good-luck telegrams when he opened the Venice Biennale for Ireland, press-cuttings etc and fascinating material and correspondence relating to his work as a designer, which the exhibition now draws attention to.

The decision to install Kite! in the main exhibition space at VISUAL influenced all others decisions for that space. It was always my intention to situate the Gold Paintings there and the challenge was to find some way of marshalling the vast gallery space. The reason to paint was twofold: to provide a strong background for the Gold Paintings as well as to create a sort of architectural intervention.

A frieze of translucent white glass nearly 4m deep comprises the top ‘one third’ of the main space and admits a quality of filtered daylight that immerses everything and causes objects to seem to emit light. I decided to paint running sections of the walls a chalky dense black, to a height of 380cm but not all the way to the corners so that the space might retain a fluid, open feeling. In effect it divided the wall into three horizontal zones: daylight, white and black. Twelve years earlier for his retrospective, Pat had had certain rooms of the Hugh Lane Gallery painted cobalt blue, a deep ‘studio’ green and what he called ‘bull’s blood’ red as the settings for the Gold Paintings. The effect was extraordinary.

A few months ago, when I visited the Tate’s Paul Klee exhibition I was struck by the effect on the works of the incidental black walls that punctuated the exhibition. Influential too was a passage from Mel Gooding’s essay about Scott’s work which begins by referencing Junichiro Tanizaki’s In Praise of Shadows, which marvels at the wonderful ability of gold to capture a mere glimmer of light “then suddenly send forth an ethereal glow, a faint golden light cast into the enveloping darkness, like a glow upon the horizon at sunset… gold retains its brilliance indefinitely to light the darkness of a room”.

In my mind, the black wall functions variously as a sort of shadow space, a dark cloister, a cinematic zone, a metaphysical place from which the Gold Paintings emerge, with sculptural effect, while the orange and black painted drawing that is Kite! magnetizes the floor space.

“Brave,” Eric Pearce described it!

Lunch Bytes at IMMA with Melanie Bühler

I am very much looking forward to the first Lunch Bytes event in Dublin that will take place tomorrow at IMMA as a collaboration between the Goethe-Institut and IMMA.

Lunch Bytes is a series of events dedicated to art and digital culture. I initially conceptualized this format of public discussions for the Goethe-Institut in Washington DC and Smithsonian’s Hirshhorn Museum in Washington DC. After a first series of discussions had successfully taken place in 2011, a second season of events, which also included evening events, took place in 2012.

Lunch Bytes’ events in Washington DC

Moreover, Lunch Bytes became a space to exhibit digital art online: “Platform”, a section of the Lunch Bytes website showcases work by emerging artists who explore digital formats.

In 2012, we concluded the series in Washington DC and I was invited to organize discussions as part of Art Basel Miami and Art Basel.

[youtube http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xqiHJ0Sixxs]

Video Art Basel Miami

Now, Lunch Bytes is coming to Europe. Launched as a project by the Goethe-Institut Northwest Europe, the Goethe-Instituts in Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Dublin, Glasgow, Helsinki, London and Stockholm will set up discussions about art and digital culture throughout 2014. The events will refer to four major themes: Medium; Structures and Textures; Society; Life.

The project will culminate in an international symposium to be held in Berlin in 2015.

The first event in Dublin entitled Medium: Film/Video, will centre on the notion of the ‘medium’ and examine the ways in which digitisation and networked computing have restructured the formats we work and think with when it comes to art practice in general and to the medium of film in particular.

We invited Irish and German artists and experts to discuss this theme and to prepare a short presentation, which relates their background to the topic of the talk.

Dublin-based artist Saoirse Wall will present her work and discuss how online culture has impacted the formats she works in.

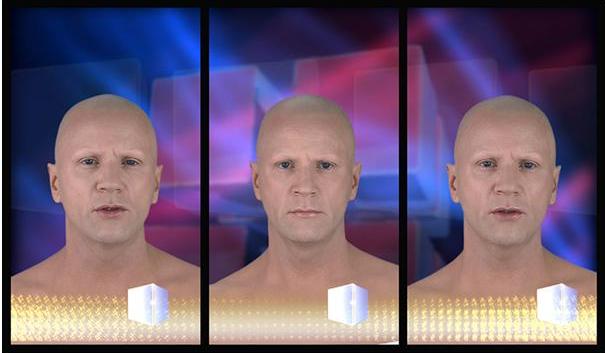

The German artist Bjørn Melhus who started to work with films in the late 80s, and became one of the most famous German video artists in the 90s, will look back on his body of work, which reflects how the filmic medium has evolved over the course of the last 20 years.

Berlin-based theoretician and art critic Stefan Heidenreich will reflect on how the moving image has evolved in online culture.

Maeve O’Connolly, lecturer in the Faculty of Film, Art & Creative Technologies at Dun Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design & Technology, who will also chair the discussion which will follow the presentations, will examine the question if it still makes sense for artists and curators alike to operate with categories like film and video in our post-cinematic, post-broadcast, and post-internet era.

Melanie Bühler, curator of Lunch Bytes