Visual Art, Audiences & Ireland. 50 years on, what can we learn from Rosc?

By Sarah Glennie – Director, IMMA (2012 – 2017)

When the 50th anniversary of the first Rosc came onto the radar of the programming team at IMMA we sent a long time discussing what our response would be. It seemed that instead of taking an art-historical survey of the work included in Rosc, and instead taking a broader consideration of the context in which these ambitious and daring exhibitions took place would deliver the potential to open up new histories that could inform our thinking about the potential and place of visual art in Ireland today. As curators working in a visual arts institution we were interested to find out how they had happened? Who paid for them? What else was happening at the time both locally and internationally and crucially what did people think of these exhibitions?

Our ongoing partnership with NIVAL has allowed the team working on the ROSC 50 project to use Nival’s extensive and rich Rosc archive to delve into some of these questions. Our position as a public institution has given us an opportunity to capture what is often missing from exhibition histories – the memories of the people that actually saw the exhibitions.

It has been a fascinating journey and as we come to the end of the project we are beginning to reflect on some of the striking things that have emerged – areas of consideration that we want to explore further over the coming months and years.

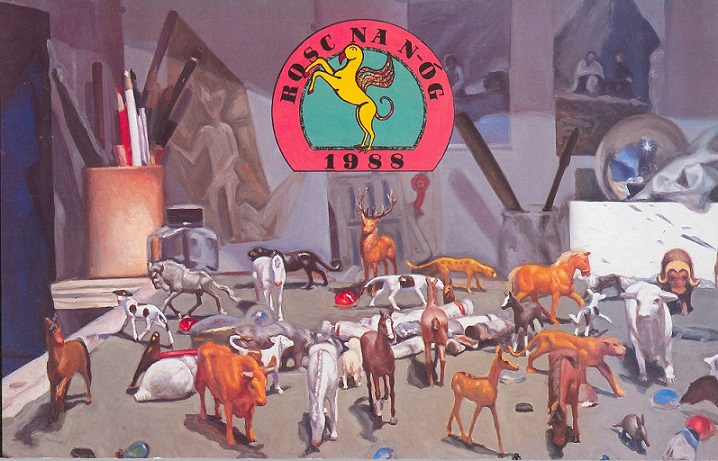

I myself arrived in Ireland to work at IMMA in 1995, very much in the aftermath of the last Rosc (1988) and the opening of IMMA (1991). Discovering more about Rosc over the past year has radically shifted some of the narratives about Irish visual arts that I encountered at that time and has given me new perspectives on many of the things that continue to shape working in the arts in Ireland today. This text is my own response to ROSC 50 and some of the things I have learned.

The Contemporary, the Untested and the Radical

Some extraordinary art was included in Rosc. The list of names gathered in the timeline accompanying this project is startling in its ambition, global reach and representation of the artists credited with defining contemporary art in the last 50 years. The list is also very male and not very Irish and that is another story in itself. What this ambition and reach does demonstrate however, for all its much debated flaws, was a belief in the value of the contemporary, the untested and the radical. John Latham was at the opening in 1967, Laurie Anderson performed in Trinity in 1980; that was a revelation to me.

The politics and finances behind Rosc were complicated and troubled and have been much debated elsewhere. It is a simplification to say that those that initiated the Rosc project were visionary, but despite the complexities, looking at Rosc from 2017 Ireland as someone working in the arts it stands out as a moment when the state significantly backed art that was unknown, untested and unfamiliar. Rosc struggled for money but an examination of the figures is telling – the overall exhibition budget for 1988 was over £300,000, figures that are comparable to the current expenditure in euros of EVA International, Ireland’s biennial of Contemporary Art, some 30 years later. The Hugh Lane’s much debated acquisitions budget in 1977 when they purchased the Agnes Martin painting from Rosc, is close to the amount IMMA has at its disposal in 2017, raised through corporate and philanthropic support. Would Rosc be possible now?

Rosc for every Schoolchild

Rosc contributed to the growing awareness of the paucity of visual arts education in schools in Ireland and action was taken to address this. The legacy of this promise has not been realised. The Minister of Education in 1967 created the wonderful precedent that all schoolchildren should be given the opportunity to visit Rosc, assisted by an arrangement with CIE (now Irish Rail). In 1980 Carl Andre made a beautiful guide of the exhibition for children starting with the memorable phrase ‘Art is what children have to stop doing in order to become grown-ups’. One of the international visitors to the ’67 Rosc was struck by the amount of school groups queuing to get in and the numbers of children visiting are startling for each subsequent exhibition. Reflecting back it seems that the baton was dropped. Battles are ongoing for the provision of visual arts education in secondary school with the junior and leaving cert curriculum giving little encouragement for students to critically engage with the art of their time. The leaving cert paper in 2017 contained questions about Stone Age Art and Louis Le Brocquy – a magnificent painter but one who has been deceased since 2012. No questions appeared about living artists.

Rosc contributed to the growing awareness of the paucity of visual arts education in schools in Ireland and action was taken to address this. The legacy of this promise has not been realised. The Minister of Education in 1967 created the wonderful precedent that all schoolchildren should be given the opportunity to visit Rosc, assisted by an arrangement with CIE (now Irish Rail). In 1980 Carl Andre made a beautiful guide of the exhibition for children starting with the memorable phrase ‘Art is what children have to stop doing in order to become grown-ups’. One of the international visitors to the ’67 Rosc was struck by the amount of school groups queuing to get in and the numbers of children visiting are startling for each subsequent exhibition. Reflecting back it seems that the baton was dropped. Battles are ongoing for the provision of visual arts education in secondary school with the junior and leaving cert curriculum giving little encouragement for students to critically engage with the art of their time. The leaving cert paper in 2017 contained questions about Stone Age Art and Louis Le Brocquy – a magnificent painter but one who has been deceased since 2012. No questions appeared about living artists.

Local vs. International

We need to reframe the debate about the relationship between Irish and international art in Rosc and not be concerned that work made in Ireland at that time was ‘provincial’. Rosc is striking for the position taken by the various committees as to both the exclusion and inclusion of Irish Art. Again this has been well rehearsed elsewhere but this 50th anniversary programme takes place in the context of a wider curatorial reconsideration taking place around the world/internationally about how the decisions have been made about the art that is deemed ‘important’ from the last century and what may have been lost or overlooked in these dominant narratives. Many museum collections would lead us to believe, as Rosc did, that important artists lived only in New York or Europe and were predominantly white males. Curators and art critics internationally are now looking beyond these narrow parameters to the work made by women, or by those working away from the centres of the art market. Indeed we do this ourselves in IMMA with the Modern Masters series re-examining artists such as Gerda Frömel or Patrick Hennessy. Previously overlooked work is being reassessed on its own terms, for its specificity and not by its ability to keep up with the dominant international art movements of the time. The ‘local’ is now recognised as having value – interestingly something Brian O’Doherty recognised in his introduction to the 1971 Rosc ‘fringe’ exhibition The Irish Imagination which showcased work being made in Ireland at the time. Within this new paradigm this so called ‘fringe’ exhibition could be seen as worthy of study by art scholars as something unique and culturally specific to Ireland, in contrast to the main Rosc exhibition with its focus on reflecting ‘important’ international art of the time.

Much was written at the time and since about the wisdom of the early position taken by the Rosc committee to exclude Irish art in order to bring work to Ireland not otherwise seen here. There is no doubt there was a need for this. Kathy Prendergast, when contributing to our recent artists’ panel discussion reflected on the impact of seeing, in 1980, the kind of art that she didn’t even think was possible, though she was despite being a recent graduate of NCAD. It is clear that Rosc compounded a view that Irish visual art was out of step and therefore irrelevant. As the art world broadens its view on the past it is timely that Rosc and its troubled relationship with Irish art is re-examined.

Audience Reaction

It is evident that a lot of people really genuinely enjoyed the Rosc exhibitions and were very glad they saw them. This may not be what the media wanted to believe at the time, but our anecdotal, and admittedly limited, gathering of audience responses over the last few months has confirmed what we see continuously in our galleries – audiences in Ireland are willing to embrace the unknown, they like to be challenged and are open to a wide range of artistic expression.

Many of our respondents were schoolchildren or students at the time and it is striking how many credit the experience of seeing Rosc as opening up new possibilities for them. Letter writers to the Irish times and commentators in the media seemed determined that the public could only be appalled and confused by the Rosc exhibitions. An RTE film from 1988 included in the Rosc 50 project shows a bemused Ray Darcy determined to encourage young people to declare their disgust, confusion and ridicule of the exhibition asking them if it is all ‘gobbledygook’. Apart from a few embarrassed teenage giggles generally the young people seem very prepared to give the work a chance. They may not like it all but they are prepared to consider it. To Darcy’s obvious surprise one girl gives an extremely astute reading of the infamous Tim Rollins and KOS work portraying Haughey as the dog in Animal Farm. This one example is by no means representative of all audience reaction, but a comparison of the media coverage at the time with our captured audience memories suggests that it is time to reconsider the relationship between audiences and visual art in Ireland. The audience has been there all along, constantly growing and not very shockable. Yes, there is more work needed to be done to broaden and deepen the range of audiences accessing culture in Ireland, but wouldn’t it be nice to think that a visit to a contemporary gallery was part of every child’s school experience today. Think about the audiences those children would create in the future, another fifty years from now.

This post alongside a new text by Jonathan Carroll is included in EDITION #001 of the IMMA EDIT. Subscribe to the IMMA Mailing List and select ‘IMMA EDIT’ to receive the future quaterly editions of the EDIT.

Categories

Further Reading

Exploring NIVAL for the first time / ROSC 50

This year IMMA and NIVAL are collaborating on 'ROSC 50'; a project that seeks to examine the pivotal and sometimes controversial Rosc exhibitions held in Ireland from 1967 to 1984.

Introducing ROSC 50 – 1967 / 2017

In collaboration with the National Irish Visual Arts Library (NIVAL), IMMA is marking the 50th anniversary of the first Rosc exhibition, in 1967, through a programme of events which will unfold over the cour...

IMMA celebrates the ten-year anniversary of The Burial of Patrick Ireland

Emer Lynch, Curatorial Assistant, Collections, IMMA reflects on the decade that has passed since The Burial of Patrick Ireland and the artist's recent visit to IMMA where he was awarded the Freedom of Roscom...

Video. Brian O’Doherty, a new rope drawing at IMMA

In this video, Christina Kennedy (Senior Curator, IMMA) provides an in-depth look at a new rope drawing by Brian O'Doherty.

Up Next

Paint Skin? - a blog by Irish Artist Susan Connolly

Sat Dec 16th, 2017