The artist as flâneuse, a walking cultural commentator

Beth O’Halloran, Visitor Engagement Team at IMMA/lecturer at NCAD, looks at the transgressive role of female artists as cultural ethnographers – in particular the artist as flâneuse. Included are references to works by Isabel Nolan and Sophie Calle, exhibited in IMMA currently and 2004 respectively, and writers Rebecca Solnit and Virginia Woolf.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..….

With Covid’s constraints on movements in tandem with its release from work and school commutes, daily walks have become important de-stressing moments for many of us. Which calls to mind the 19th-century phenomenon of the flâneur – that figure of privilege with time to aimlessly meander and observe – famously most extreme in 1840, at the height of Industrialization’s manic urban activity, when it was good form to lead turtles on walks through the arcades to enhance the slowest gait possible. It is a given that these early flâneurs were male and their recordings of everyday occurrences were weighted by their gender alone. But, author of Flâneuse: Women Walk the City, Dr Lauren Elkin, sheds light on recent instances of the female pedestrian perspective – “The flâneur – the keen-eyed stroller who chronicles the minutiae of city life – has long been seen as a man’s role. From Virginia Woolf to Martha Gellhorn, it’s time we recognised the vital, transgressive work of the flâneuse.” [1]

Virginia Woolf called it “street haunting” in an essay by that name: sailing out into a winter evening, surrounded by the “champagne brightness of the air and the sociability of the streets”, we leave the things that define us at home, and become “part of that vast republican army of anonymous trampers.”

Women who walk and record – recently, attention has been given to the likes of American writer Cheryl Strayed whose walk, as chronicled in her memoir, Wild, was so personally transformative, she changed her surname to the verb. And in Rebecca Solnit’s most recent publication, Recollections of My Nonexistence, she devotes a chapter to the significance of her walks and how frightening it can be to be a woman who likes to walk in a city at night. She says, “Most urban women, you know, live as though in a war zone.” She quotes Sylvia Plath, ‘Being born a woman is my awful tragedy. Yes, my consuming desire to mingle with road crews, sailors and soldiers, barroom regulars – to be part of a scene, anonymous, listening, recording – all is spoiled by the fact that I am a girl, a female always in danger of assault and battery.”

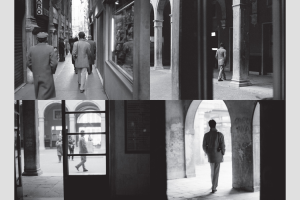

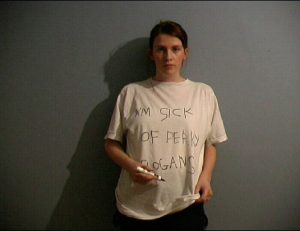

Female artists such as Isabel Nolan and Sophie Calle , navigate the contemporary female experience. They comment on interactions with their personas and the public in both highly personal and universal terms. Nolan’s says of her work, Sloganeering 1-4, that she wanted to “create a character who is trying, somewhat desperately to communicate a sense of their identity … in a culture where communication is often reduced to sound bites that are often both pretentious and vacuous”. She upends the ubiquitous and thereby nearly invisible realm of T-shirt slogans as a way to communicate in the public sphere.

Her casual scrawl is similar to graffiti artists and their ‘tags’ – hastily written codified messages. Calle’s practice can be termed a social ethnography. Calle’s work often focuses on human vulnerability, identity and intimacy. She is recognized for her detective-like ability to follow strangers and investigate their private lives. Both artists call to mind Virginia Woolf’s words: ‘What greater delight and wonder can there be than to leave the straight lines of personality – that one is not tethered to a single mind, but can put on briefly for a few minutes the bodies and minds of others.’ (Street Haunting, 1927).

The 19th-century Russian painter Marie Bashkirtseff said, “I long for the freedom to go out alone: to go, to come, to sit on a bench … and to stroll in the old streets in the evenings. This is what I envy. Without this freedom one cannot become a great artist.”

Artists such as Calle and Nolan, Strayed, Woolf and Solnit show us the power of navigating this new-found, albeit still limited, freedom and the weight of the female gaze.

[1] https://www.theguardian.com/cities/2016/jul/29/female-flaneur-women-reclaim-streets.

Categories

Further Reading

At Home With Louise

To mark the tenth anniversary of Louise Bourgeois death, Brigid Mc Clean time travels to take another look at Bourgeois’s exhibition, Stitches in Time, shown at IMMA seventeen years ago.

Helen Cammock: The Long Note at IMMA by Eva Kenny

In association with IMMA's 2019 programme, Dublin based writer and researcher Eva Kenny explores overlapping themes of borders - Northern Ireland, Brexit and Civil Rights, that comes to the fore in Cammock’s...

Women, feminism and art

IMMA's Lisa Moran examines the current emphasis on women and art in IMMA's 2013/4 programme, reflecting on how it draws on and highlights IMMA’s rich history of exhibitions featuring female artists, who have...

Up Next

Statue Wars

Mon Jul 13th, 2020