Encounters with Freud

We invited Fionna Barber, Reader in Art History at Manchester School of Art, to respond to Gaze, the third exhibition in the IMMA Collection: Freud Project. The exhibition is concerned with the human gaze; of the artist, the sitter or the viewer, and presents Lucian Freud’s work alongside those of artists from the IMMA Collection. In her text, Barber explores the nuanced relationship between these artworks.

During his long career, Lucian Freud acquired a reputation for the remarkable intensity of his paintings. The psychological insights of the portraits and self-portraits for which he is best known, or the intuitive subtlety of his depictions of animals and even the occasional landscape, all testify to his ability to transform the acuteness of perception into vivid representation. These are works that suggest an immanent presence, whose subjects are caught in a trance-like stillness from which they will soon awaken. In many of the portraits the artist’s gaze is reflected back in the steady, open-eyed focus of his sitters, an uncomfortable intimacy that was the product of innumerable sessions in his London studio over weeks and months. Each painstaking brushstroke thus becomes a trace of the relationships between artist and sitter – often family, as in the double portrait of his young daughters Bella and Esther (1987-1988), friends or lovers – played out across the surface of the canvas. Freud’s incisiveness is echoed here in Thomas Ruff’s Portrat (2001), where the frontality and monumental size of the photograph make for disconcerting viewing.

Lucian Freud became one of the canonical figures of British post-war painting, a central figure (with Bacon and Kitaj) in the so-called ‘School of London’. However his relationship with Ireland was well established long before the posthumous celebration of his work in the Irish Museum of Modern Art’s Freud project, or the major retrospective that preceded it in 2007. During the 1950s he spent a lot of time in Ireland, on occasions painting in Patrick Swift’s Dublin studio; this was also the period of his marriage to Caroline Blackwood, the Guinness heiress. Yet Freud was additionally a painter of the Irish diaspora. His neighbours and acquaintances, such as the Two Irishmen in W11 (1984-1985) dressed for the occasion in their best suits and with the West London cityscape visible through a window behind them, make frequent appearances in his work. But he could also be very particular about his sitters, famously refusing to paint Andrew Lloyd-Webber on the grounds that his face was ‘too soft’.

The intensity of the artist’s scrutiny, discomfiting and revelatory, is a premise for the exhibition Gaze in which pieces from IMMA’s extensive collection are displayed in conjunction with a selection of works by Freud that are on extended loan to the gallery. And if you detect the presence of the artist and his acute visual assessment through his paintings included here there is also a sense in which the other works, in turn, look back at Freud. In a manner not dissimilar to the relationships played out within the artist’s studio, the spaces of the gallery become the venue for an ongoing dialogue in a series of curated conversations about portraiture, the body, the role of the artist that often cross boundaries of time and medium. In one room the photographs of two iconic performances from 1975 by Marina Abramovic, Art Must be Beautiful, Artist Must be Beautiful and Freeing the Body confront Freud’s Naked Portrait, Fragment (2001); the photographed body in movement brushes uneasily against the dreamlike stasis mapped out in oil and charcoal.

In another, the relationships between humans and animals are explored through a pairing of the Triple Portrait (1987-1988) with Dorothy Cross’ Lover Snakes (1995). Ultimately, however, what is at stake here is the transformation of the artist’s sensual appropriation of the world into a material form that embodies that knowledge, in turn becoming the basis also for the elusive formation of meaning in the shimmering space between artwork and spectator.

The nuanced relationship between the works displayed in Gaze is immediately apparent in the first room of the exhibition, where the roughly chiselled surface of Stephan Balkenhol’s Large Head echoes the impasto of many of Freud’s later portraits. Its similarly disconcerting psychological engagement with a male subject also speaks to the construction of masculinity suggested by a selection of Freud’s depictions of men, several of whom were his Irish acquaintances – the Donegal Man (2006), or the earlier Head of an Irishman (1999).

Yet the curatorial decisions that have gone into the making of Gaze have also led to the inclusion of works that actively challenge some of the associations forged within Freud’s paintings. Irish masculinity, for example. features in a very different way in Pauline Cummins’ tape/slide installation Inis t’Oirr / Aran Dance (1985).

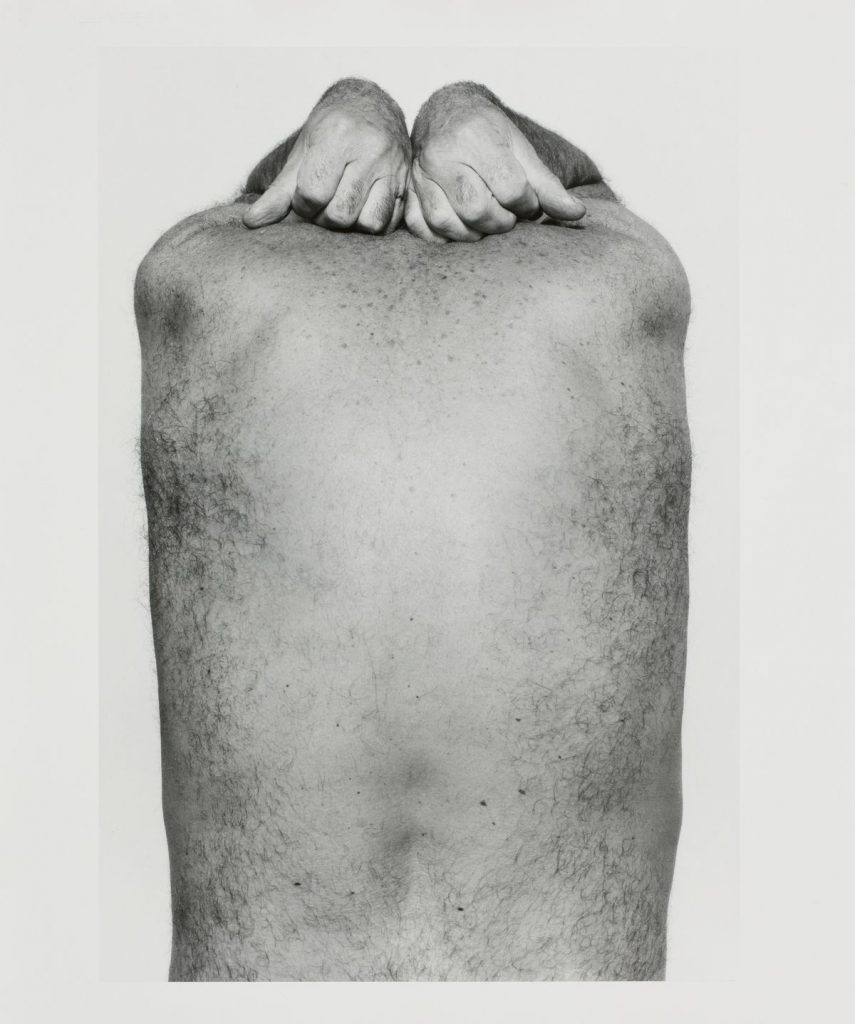

The male body as an object of (female) desire is a theme notably absent from the work of an artist renowned for his countless affairs with women, as the result of which he fathered at least fifteen children. Instead, the matching of two nearly contemporaneous self-portraits by elderly male artists, Freud and the photographer John Coplans, suggest a degree of reciprocity, a quietly incisive interrogation of aging masculinity registering through skin and the softening of muscle beneath. And in the end, it is flesh that remains; the knowledge of all of these bodies, many of whom are long gone, that remains caught by the waiting gaze.

About the author

Fionna Barber is Reader in Art History at Manchester School of Art. She is the author of Art in Ireland since 1910 (Reaktion 2013), co-editor of Ireland and the North (Peter Lang 2019) and curator of the exhibition Elliptical Affinities: Irish Women Artists and the Politics of the Body 1985-present, Highlanes Gallery Drogheda 16 November 2019 – 25 January 2020.

About the Exhibition

The IMMA Collection: Freud Project, Gaze continues until Sunday 19 May 2019 in the Freud Centre. Tickets €8/5. Book online. Gaze is curated by Johanne Mullan, Collections Programmer, IMMA.

Categories

Further Reading

Slow Looking & Porous Links in The Ethics of Scrutiny in The Ethics of Scrutiny

Writer and researcher Sue Rainsford sits down with artist Daphne Wright to explore her curation of the IMMA Collection: Freud Project exhibition Ethics of Scrutiny.

Daphne Wright, Freud and the poems of Emily Dickinson

We invite Arthur Seefahrt poet, writer and member of the IMMAs Visitor Engagement Team, to reflect on the fascinating ecology that underline Wright’s curatorial configurations of Freud, and inclusion of the ...

Landmark Lucian Freud Project and 2016 programme

IMMA announces landmark Lucian Freud Project for Ireland alongside an expanded 2016 programme of new work celebrating the radical thinkers and activists whose vision for courageous social change in Ireland a...

Up Next

Helen Cammock: The Long Note at IMMA by Eva Kenny

Thu Apr 18th, 2019