Walker and Walker

Walker and Walker have collaborated professionally since 1989 and have become one of Ireland’s most highly regarded artists internationally. Nowhere without no(w) showcases a number of pre-existing works from the artists’ extensive 30 year career with a series of new works responding to their ongoing research into language, its meaning and its construction. Here Joe Walker provides a detailed contextual walkthrough of the exhibition, exploring individual works in depth.

Room 1

On entering the exhibition, you encounter the first work almost unconsciously: the usual door handle leading into the gallery has been replaced with a door handle designed by Walter Gropius, a 20th century German architect, urban planner and theorist. The handle is both a tactile introduction to Walker and Walker’s work, while also immediately linking you to the canon of art, design and literature from which their work takes influence and inspiration.

Walter Gropius nickel-coated brass door handles

4 x 11 x 5 cm

But while the handle is a specific cultural artefact, it also possesses a unique personal history made visible in part by the aged patina. The once nickel plated handle is now almost completely eroded by usage, exposing the underlining brass body, speaking of those who came in contact with it over the course of time, and possessing a presence of a past which is unique to itself and continues to develop for the duration of the exhibition.

The presence before him was a presence (Henry James) is a neon text written in reverse, continuing Walker and Walker’s series of works fabricated in neon. These works are often hung facing windows or only seen clearly as a reflection. In this case, viewing the neon sign in the black mirror opposite it reveals the words ‘the presence before him was a presence’. This phrase is taken from The Jolly Corner, a short story by the American writer Henry James in which the protagonist is confronted with a ghostly alter ego. This ghost represents the different paths he could have taken in his life, and consequently, the different people he might have become. In Walker and Walkers work, their concern is to suggest a presence that accompanies the viewer throughout the exhibition, oscillating between the material and immaterial. To view the work one turns away from its physical manifestation, to a reflection in a mirror, augmenting the sentiment of the work.

In an effort to uncover its origin and/or in the process compromising it features a wallmounted vitrine containing a single pearl. A natural pearl grows in a layered formation, in a similar way to tree rings. The pearl in the vitrine has been hollowed out, in an attempt to identify the miniscule piece of grit that marks the beginning of its formation, within the shell of an oyster. In the process, the pearl has been corrupted, and has taken on a new form.

Full stop is a circle of silver embedded in the wall, its reductive form adhering to one of the basic shapes of geometry. A punctuation, a pause, an instruction to breathe, Full Stop occupies the space between the ending of a sentence and the beginning of something new. Over time the silver will tarnish and eventually become black, changing from bright to dark.

Accompanying these works, a stainless-steel circular sculpture adhering to the language of minimalism is placed on the floor. Almost an ubiquitous object, it is a tree holder or a protective guards usually seen on some city streets. Picking up on the motif of zero which addresses the notion of absence, loss, or the void, this object is in essence is designed in time to be obsolete; as the tree outgrows its designated circle, each defined space is removed in turn. This work identifies another ongoing theme within Walker and Walker’s work; the tension between presence and absence. In waiting (Oak tree) is an object filled with the potentiality of the physicality of a tree but is also filled with a certain redundancy, as it sits seemingly in a state of exile.

Alcove 1

Echoing the crew in the film Mount Analogue Revisited, awaiting the appropriate circumstances to enable them to enter the shores of the island, a taxidermy owl The Owl of Minerva spreads its wings with the falling of the dusk’ sits perched high above the gallery. Clearly it will never fly but as the title declares, it awaits a certain moment when the conditions are right, creating an enduring interval in the moment itself.

Minerva, the Roman goddess of wisdom, was associated with the owl, traditionally regarded as wise, and hence a metaphor for philosophy. Hegel wrote, in the preface to his Philosophy of Right: ‘The owl of Minerva spreads its wings only with the falling of the dusk.’ He meant that philosophy understands reality only after the event. It cannot prescribe how the world ought to be.

Beneath the owl, is a drawing of Arthur Rimbaud. The title references Rimbauds poem Vowels in which he assigns colours to vowels, adding another complexity or synaesthesia to language and sets up a dialogue with the work in the following room I say: a fl w r!, where these same vowels are absent.

Alcove 2

A work Dusk consists of two threads, one black and one white running from floor to ceiling. Placed in the space so that there will come a point at dusk, where through the loss of light, one can no longer distinguish one thread from the other.That which is in opposition to each other, black and white, over time becomes indiscernible. Night takes away the very of proof of the threads existence, in time one will witness nothing in the darkness. Indeed night can take away the proof that we exist, at least to each other.

Room 2

In this room, the nature of language is explored further. Aluminium lettering suspended on the wall spells out the phrase I say: a fl w r! And there arises musically, and its very essence, that which remains absent from every bouquet.’ This phrase is taken from an essay by the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé. Reflecting on Mallarmé’s desire to liberate language from what it signifies, Walker and Walker have deliberately omitted the vowels from the word ‘flower’, to emphasise the declarative nature of the sentence and its conflict with its own textuality, creating a tension between orality and the written word.

Another ongoing concern of Walker and Walker is engaging with and re-examining moments and works from art history. The work Widow’s pane, or bachelor’s even, after Marcel Duchamp, after Charles Baudelaire connects two reference points for the artists. The first of these is the highly influential artist Marcel Duchamp. A Conceptual artist, he presented objects with their meanings obscured or reconfigured, similar to Walker and Walker’s concern with language and form.

Charles Baudelaire, the French poet, is another influence in his exploration of language and translation, particularly that of Edgar Allen Poe. Window, after Marcel Duchamp, after Charles Baudelaire is a reworking of Duchamp’s Fresh Widow and draws reference to Baudelaire’s prose poem titled ‘Window’ (published in the Walkers artist book Return Inverse and placed on the gallery window sill nearby) in which he celebrates the opacity of these links between what is public and private, that simultaneously pierce and reinforce the barriers between us and the outside world. The poem makes references to the poet witnessing an elderly person though a closed window which elicits within him an empathy for his own humanity, despite the potential of it being fictional. The reflection in the black perspex of the Walkers window throws the gaze of the viewer back upon him or herself, while simultaneously references that which lies beyond, a site of contemplation, out of view.

A bronze head with a black patina sits on a plinth, Portrait of Charles Baudelaire after Raymond Duchamp-Villon is a remodelling by the Walker brothers of a portrait of Baudelaire that was made by Raymond Duchamp Villon, brother of Marcel Duchamp in 1913. The portrait is a severe representation with a large crown for the head and a down-turned mouth which can be attributed to Edward Manets representations of Baudelaire. Baudelaire had been dead for almost half a century before Duchamp-Villon made his portrait. Remodelled here, with his smooth and swollen dome, his ruthless nose, and dead, unseeing, angled eyes, the unsettling nature of the work makes reference to the severity of a Roman or French Gothic sculpted head but is ultimately modernist in its form.

Housed within the bronze head are three objects, a lump of clay, a ruby and a meteorite which reference other representations of Baudelaire that can be attributed to Stéphane Mallarmé. In Mallarmés poem The Tomb of Charles Baudelaire, the initial image is not actually that of a tomb but of the dead poet himself. The buried temple refers to Baudelaire’s body, which, though already buried in the Montparnasse cemetery, still has mud and rubies issuing from its mouth, a reference to both the profane and the beauty contained in Baudelaire’s poetic utterances.

The meteorite refers to Mallarmé’s portrayal of Edger Allen Poe’s tomb as a kind of meteorite emphasising Mallarmé’s perception of Poe as an extraterrestrial. Baudelaire over the course of time had employed Poe as his final and most inducing intercessor, a means to navigate his complex political and artistic practice. This unique relationship is addressed in all it complexities in Walker and Walker’s play Return Inverse, a copy of which sits on the windowsill.

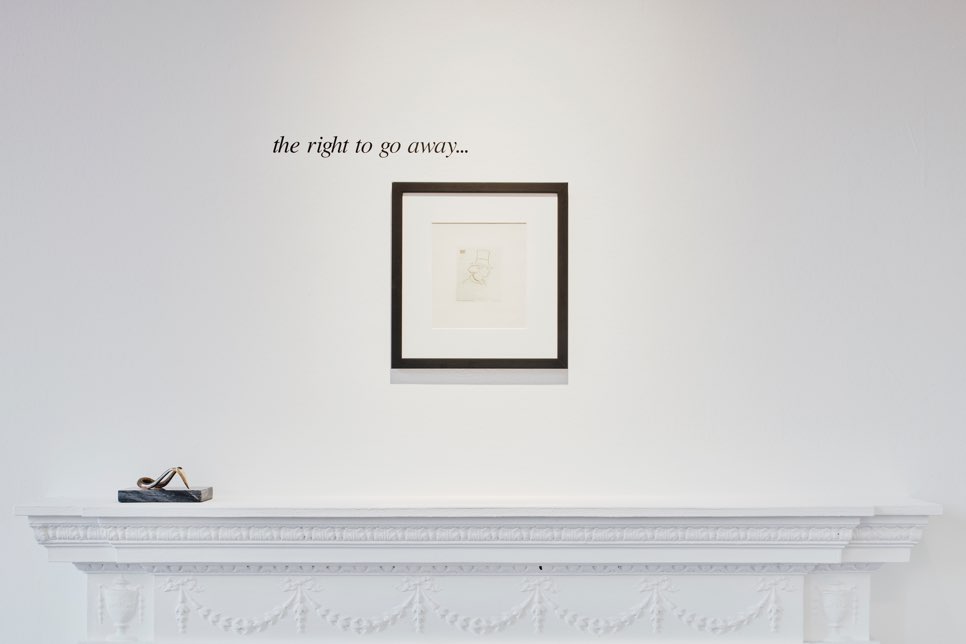

On the wall above the fireplace is an etching of Baudelaire by the French modernist painter Édouard Manet, a preliminary study for his work Music in the Tuileries, which is in the collection of Dublin City Gallery, the Hugh Lane. Making reference again to the complexity between presence and absence, the etching is shown coupled with the text on the wall of the gallery ‘The right to go away’ which makes reference to Baudelaires desire for the right for a person to disappear to be brought into law and also an unnamed object, a small bronze sculpture, ambiguous in form and meaning sitting on the fireplace that remains untitled and uncredited within the exhibition.

In Manets painting, Manet situates himself to the far left of the painting, prompting comparisons between himself and the painter Diego Velázquez. Velázquez is credited for bringing a greater psychological complexity to art, whereupon scrutinising his masterpiece, Las Meninas, the relationship between the observer and the observed is brought into question, where the viewer stands in the place of the King and Queen whose portraits Velazquez is painting. Walker and Walker are interested in how Manets painting plays with similar concerns. In the painting of a gathering of people, the viewers occupy a similarly fictionalised space, the space where the musicians in the orchestra should be. The viewing of this painting sets the scene for the play-within-a-play that occurs in their play Return Inverse.

“BAUDELAIRE: Where else is the music of the title coming from, if not from us?” Return Inverse, Walker and Walker

Further undermining any fixed state, two incandescent light bulbs hanging together from the gallery ceiling Communion are programmed to concurrently fade up and down over a period of 6 minutes, maintaining a continual active state in communion with one another as if breathing, negating a simple binary of on or off.

Corridor

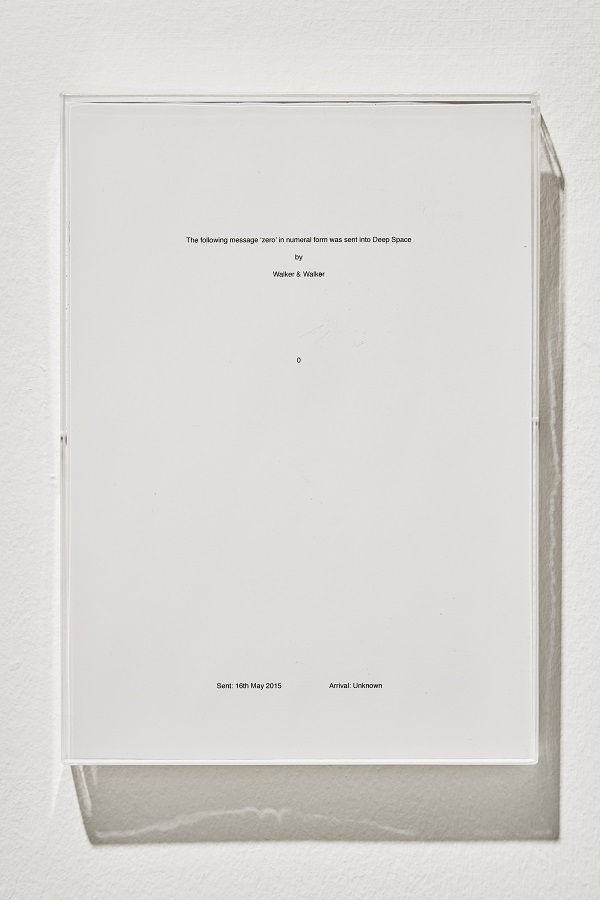

In the corridor, a simple framed certificate titled Void, certifies to an event of the numeral zero being sent into deep space using radio technology. Its arrival unknown, a void within the void of space. The number zero is implicitly linked to the protocol of launching a rocket into space with the use of the countdown system. Zero is a symbol of nothing, the absence of any quantity, in the Jewish Kabbalah zero represents all that is boundless and beyond human control, the form resembles a circles having neither beginning or end, its elliptical shape represents both rise and fall.

Proposition adhered to consists of the fixing a postcard of a Sigmar Polke painting at the entrance before the space where Walker and Walkers film is shown in the manner of a film poster or announcement. Bearing the text “Hohere Wesen befahlen : rechte obere Ecke schwarz malen! / Higher beings commanded: paint upper right hand corner black!”, a black area was painted onto the gallery wall, extending the black and white geometrical composition of the postcard while also physically adhering to the proposition.

Room 3

Walker and Walker’s film Mount Analogue Revisited, is a reworking of Rene Daumal’s book Mount Analogue. Daumal’s final work it remained uncompleted due to the author’s premature death. The book is an unfinished story of a voyage to an unknown island, where the voyagers seek an improbable mountain which is seen as a means to link Heaven and Earth. Central to this book and the inception of the voyage, is a text about a symbolic mountain which was written by one of the protagonists but was challenged by another as being factually based.

Walker and Walker take as a starting point for their film, a short passage from the book, where upon the boat’s arrival at the shores of an island, its crew are escorted to a municipal building and asked by an official there to give an account of who they are and the purpose of their visit. Within the confines of this meeting, Walker and Walker fabricate a conversation between three of the crew members, the official and the author himself. They speak of the difficulties involved in making a journey to a superior world other than our own, where the truth cannot not exist, given the limits of reason and rationality. The events play out through dialogue within a single room, which serves to ground the fantastical nature of the film.

Although the film holds true to the book, it is not a literal adaptation, for the conversation that ensues references a broad number of writers, such as Novalis, Stanislaw Lem, Edger Allen Poe, Maurice Blanchot, Hermann Hess, William James. All of whom serve to inform a proposition for the loosening of the limits of rationality. The ending remains unresolved as the viewer is left unaware if the voyagers arrival at this place is instigated by the inhabitants of the island or by their own efforts. It is an adventurous philosophical tale, encompassing poetic passages, leading to a spiritual quest, which borders on science fiction.

Alcove 3

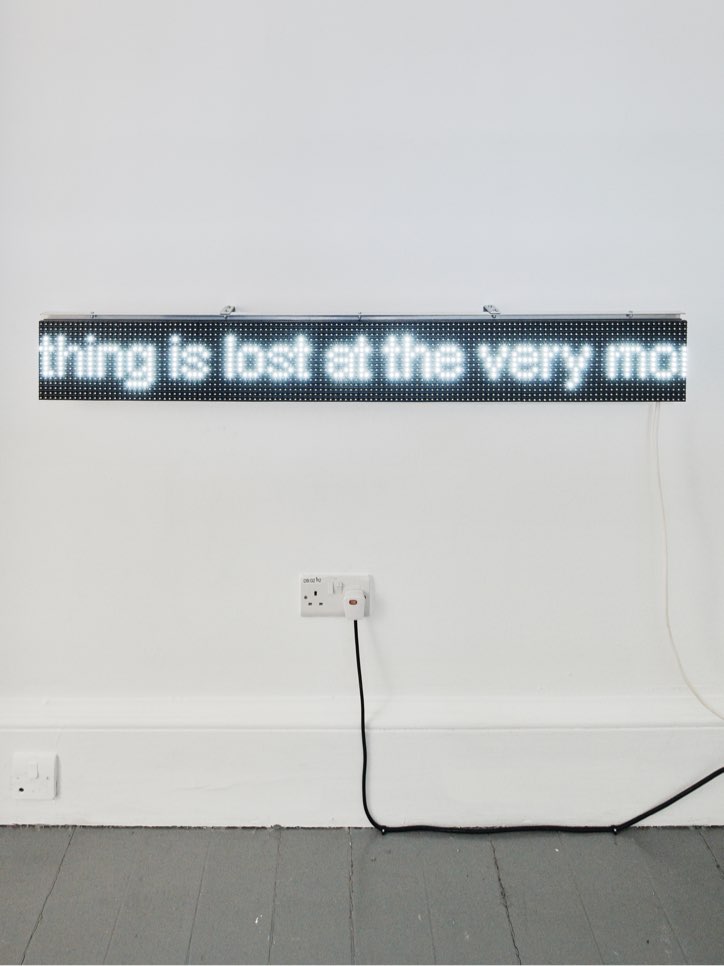

Hung low on the wall of the alcove before entering the fourth room, a single scrolling white LED sign bears the words “Take cognisance of the fact that something is lost at the very moment in which it is found”. The medium is central to the articulation and sentiment of the work, as only part of the sentence is seen at any given moment, passing in front of the viewer as it scrolls into view. The words are in essence themselves lost and found as memory comes into play.

Room 4

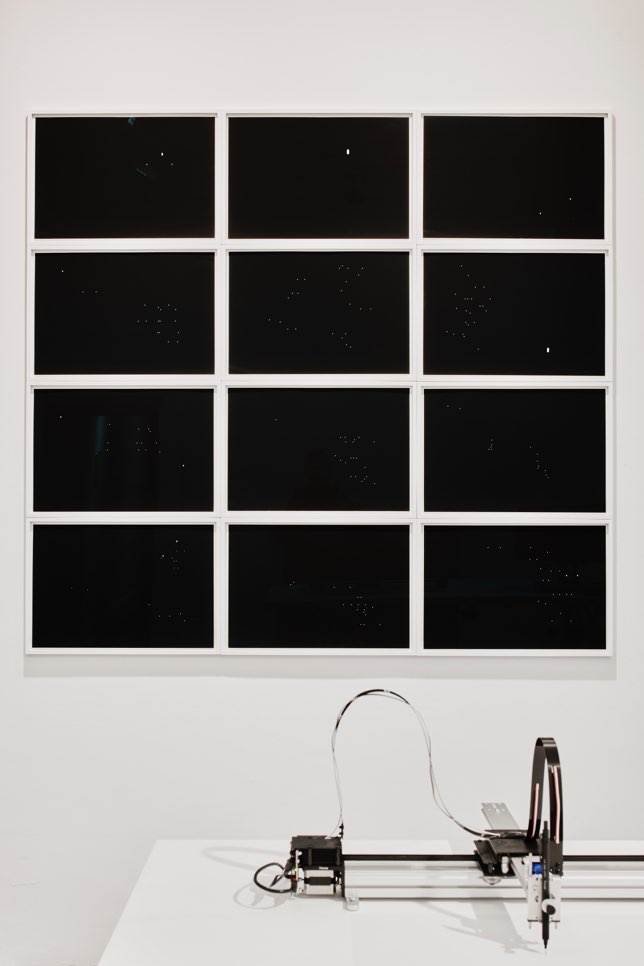

In the fourth room of the exhibition, we see the work Morning star/Evening star. On the table in the centre of the room are a drawing plotter and a computer monitor. The plotter is drawing in real time the transit of the planet Venus through space. After 8 years, Venus returns to the same place in the sky on the same date, creating an intricate circular pattern whose key points contain the markings for a pentagram or a five point star. Articulating its complex movement from the perspective of the Earth, the pattern created is referred to as the Venus Rose. The drawing will be rendered visible by the use of a line plotter, an early graphic device which creates a consistent line and unlike a printer, enables the entire process to be visible as it draws in real time the complex path of the planet as it circumnavigates the heavens.

The computer monitor on this table displays the transit of Venus translated to binary code, in synchronisation with the drawing. These two radically different visualisations of the same information reflect the fact that Venus was once thought to be two different stars, appearing in the morning and the evening. The work reflects this idea of the potential of multiple identities or concepts held within one entity. Frege in his essay On sense and reference begins by explaining the cognitive value of identity statements such as the The Evening Star is the Morning Star with regard to Venus. The distinction between sense and reference was an innovation of Frege in 1892, reflecting the two ways a singular term may have meaning. The identity between the first star we see in the evening and the last star we can see in the morning was an empirical discovery in astronomy, a piece of information that was not available by means of semantic analysing, for it is not contained in the meaning of the term used to describe the heavenly body that appears in the evening and in the morning (not a star but the planet Venus as it turns out). Frege argued, we need to recognise that meaning is a broad semantic category with multiple dimensions, and we need to develop finegrained distinctions to identify the different semantic ingredients that make up the meaning of a term.

The Venus Rose has had broad cultural references over different periods in history. In a typical Renaissance fashion, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa and others perpetuated the popularity of the pentagram as a magic symbol, attributing the five neoplatonic elements to the five points. However by the mid-19th century a further distinction had developed amongst occultists which depended on the pentagrams orientation. With a single point upwards it depicted the spirit presiding over the four elements of matter, reportedly signifying the five wounds of Christ. Whereas the influential writer Eliphas Levi declared it as a symbol of evil, whenever it appeared the other way, as a reversed pentagram, with two points projecting upwards, because it overturned the proper order of things and demonstrated the triumph of matter over the spirit.

Sometimes referred to as the Morning Star, Venus the brightest star in the heavens may be seen as a contradiction to being a symbol of Lucifer, but the role of Lucifer is complex and should not exclusively be depicted as a horned beast. Jan Verwoert in his essay Bring on the Devil discusses how the devil was embraced by the Romantics poets such as Baudelaire and Byron whose views in turn were shaped by John Milton’s Paradise Lost. Milton articulates Satan as the fallen but rebel angel and in doing so constructed him as the idol of the outlawed and as such the devil has become a prime source of identification for many different performers on the social stage of culture, a romantic role model for poets, artists, divas, dandies and disaffected teenagers.

The throw of the dice will never abolish chance is a series of prints made from Stéphane Mallarmé’s poem of the same name. This poem was published posthumously in broadsheet format using copious notes by Mallarmé of how it was to be laid out using various different fonts and sizes. Paul Valery speaks of Mallarmé as having raised a printed page to the power of the midnight sky, of a text of clarity and enigma, both tragic and indifferent. Through layering the sheets and inking out the text of the poems with the exception of where the letter ‘o’ appears, the work appears as a constellation of stars while also bears reference to the counting system of dots used on a dice.

On a chair in a corner of the gallery a book lies open that consists of a rebinding of Charles Baudelaire’s The Evil Flower in order to place two of his poems First Light and Last Light alongside each other. Creating a small internal circular narrative echoing dawn to dusk, day to night, defying closure within the larger body of work.

Walker and Walker. n-Or, 2019. Black anodized aluminium 7.5 x 19.5 x 2.5 cm.

A textual wall sculpture consisting of the letters n-Or, creating an oscillation between the closing down and opening up of the dialectic structures Nor and Or respectively.

Above the door, a plaque reads Temenos. Temenos is a Greek concept related to the border between worlds, a place marked off as holy or separate. The phrase is also used by founding psychoanalyst Carl Jung as representing a ‘squared circle’, or a space where thought and mental work can take place. The courtyard of IMMA lies beyond the door over which this work is placed, and it contains a circle within a square. Taken as a point of departure from the exhibition into the wider museum, Walker and Walker leave this plaque as a statement of intent.

Room 5

In a corner of the small final room is a night blooming flower, Selenicereus grandiflorus, a flowering ceroid cacti that blooms only once a year, for a single night.

A photograph of Alexander Graham Bell and his wife Mabel Hubbard Gardiner Bell with a tetrahedral framework, called a Space Frame, designed by Bell as part of his research into powered flight. Mabel Bell carries the structure, and encounters Alexander Bell through it. A fleeting moment both of a kiss and of a connection – an inbetween – of an interior and exterior space.

On the window two small spheres of Kilkenny limestone appear to touch, one inside the glass and the other outside. Connected by two magnets, the work is simultaneously within the interior space of the gallery and equally no longer within its confines, appearing in the exterior outdoor world. A precarious moment, each relies on the other to sustain their position and maintain their equilibrium.

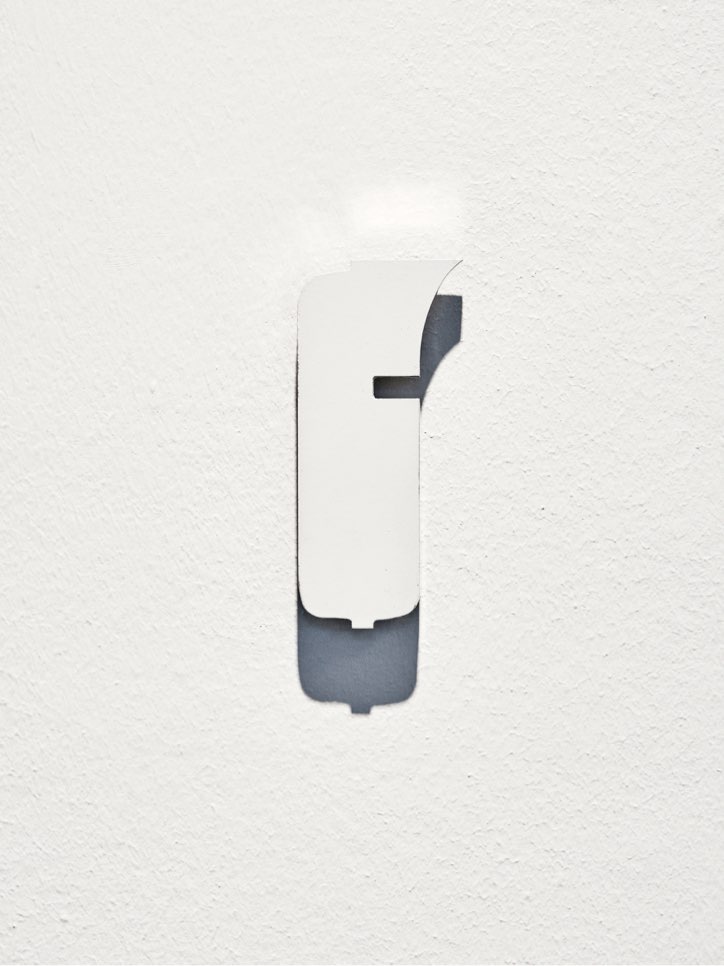

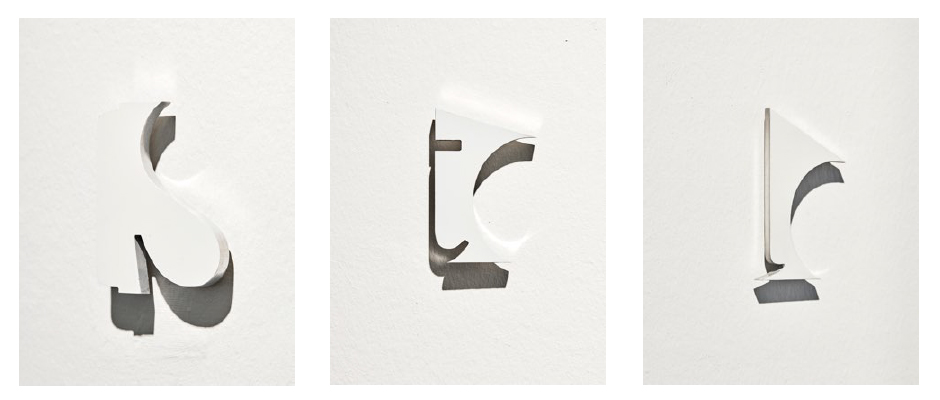

The nature of language is further explored in the In-between letters series found throughout the exhibition.

These small, seemingly abstract sculptures represent the negative spaces found between letters in words. Despite the fact that these negative spaces are encountered frequently, they remain unfamiliar and enigmatic. Making solid the empty space between the letters of different propositions and conjunctives, in what is termed kerning in typographical language, opens up a space, creating a small circular micro-narrative which undermines the didactic nature of the word itself.

Categories

Further Reading

Encounters with Freud

We invited Fionna Barber, Reader in Art History at Manchester School of Art, to respond to Gaze, the third exhibition in the IMMA Collection: Freud Project. The exhibition is concerned with the human gaze; o...

Existentialism in the (Post-) Digital Era by Charles Melvin Ess

Media theorist and philosopher Charles Melvin Ess of Oslo University, inserts the debate of ethics into the traditions of existential thinking for the IMMA Edit #002.

Exploring NIVAL for the first time / ROSC 50

This year IMMA and NIVAL are collaborating on 'ROSC 50'; a project that seeks to examine the pivotal and sometimes controversial Rosc exhibitions held in Ireland from 1967 to 1984.

Up Next

Encounters with Freud

Tue May 14th, 2019