Derek Jarman’s Garden by Susan Thomson

Besides such places as The Stonewall Inn, there are few physical places that are part of LGBTQ I+ cultural history – Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage is one of them. Writer and filmmaker Susan Thomson takes us on a journey to his cottage and garden in Dungeness, Kent.

More than 25 years after his death, inspired by Jarman’s legacy and its bleak rugged beauty, Prospect Cottage continues to be a site of pilgrimage for the LGBTQI + community. Saved from private sale through public funding, the cottage will now become a centre for a residency programme for artists, academics, writers, gardeners, filmmakers, and others interested in Jarman and his work. His personal archive from the cottage, including notebooks and letters, and the BAFTA he was awarded for outstanding British contribution to cinema, will go on long term loan to Tate Britain and will be available for public access for the very first time.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

“This year the winter never came. The sun rose blood red. At shrove tide flies swarmed. The rosemary bloomed. Eggs soured in their shells. The sky, pierced and torn, no longer sheltered the naked earth. The seasons changed. Men burrowed deep to hide their shameful poisons. For a million years thirty thousand unborn generations bound to the memory of criminal rulers, the secretaries of energy who oil the wheels of mortgage with dead hands…

I walk in this garden holding the hands of dead friends. Old age came quickly for my frosted generation. Cold, cold, cold, they died so silently. Did the forgotten generation scream or go full of resignation quietly protesting innocence. Cold, cold, cold, they died so silently. I have no words, my shaking hand can not express my fury. Sadness is all I have, no words. Cold, cold, cold, you died so silently.”

The Garden (1990) Derek Jarman

I pluck a single Calla lily from my garden to give to a friend who knew you Derek, who has lost a friend during this time, alchemist of sounds of another Blue.

Why Derek? He was my shadow side. Vocal, raging in cinematic poetry against Section 28, which banned the ‘promotion of homosexuality as a pretended family relationship’, while I and many others suffered without understanding, teenagers buried at school, in silence. He was the missing piece of the jigsaw, the images, words and music which before was empty. I may not have discovered him in time, at the right time, but even late, in my twenties, his films rented in threes from Laser video store, he was still vital in piecing together, making sense of the past, and working out possible futures, ones that were most definitely queer, but also ones that would involve film, and riches of experience, beyond the mundane, everyday, clockwork rhythms of the life that was sold to us all. Holding to his own artistic truth, in the face of commercial and political pressures, he sets a moral bar high – an ethical, aesthetic one – and shows a road worth following for the wayward.

A further twenty years later, I finally make it to visit the house where he lived, Prospect Cottage, where he decided to settle and create a garden after being diagnosed as HIV positive, in 1986. A pilgrimage, if you will. I would go during the Summer. Summer came and went. And then I suffered a loss. And two weeks later, I go.

Setting off from Brighton, I stop for lunch in a cramped café in the mediaeval, arched town of Rye, where the Pet Shop Boys live, then through Hastings and its distant rumblings of an ancient battle, roads stretching on and on, wound round and round, a straight road through a forest, and then to Dungeness as if entering another climate zone, first crossing waterlogged grasslands, wildfowl in the lake opposite EDF taking off in a collective, redstart, goldeneye, swallows and house martins, then the desert, (although the Met Office officially said in 2015 that it didn’t merit this title), a protected natural zone, ‘Site of Special Scientific Interest’, the bleached landscape of fiction, that I had seen in the moving images of my childhood and adulthood, from Dr Who of the 1970s to Jarman’s The Garden (1990), science fiction created here.

Otherworldly, so that in visiting, you feel as if you are finally entering these worlds, for the first time. The red flags, nuclear power zone, the electricity threaded, flowing in strong tangible currents flickering, twitching, alive. A déjà vu, a recognition from cinema and television, not a real memory. Now I finally am here, as if in a dream. Jarman himself imagines, following a severe storm, that someone in Ancient Rome is dreaming Prospect Cottage and his life and his films, that all of it is a fiction[1].

There is no frame around his garden, this psychic garden. Small round stones form circles of their own, primitive sundials, as if the whole garden were some complex symbol system from a mediaeval manuscript, that would give the key to what…the night sky, the motions of the planets. Sea kale, snow green. The wooden boat, with the remnants of a light turquoise paint, from its previous journeys, only just visible. It appears in The Garden (1990), fishers of men, as if it has wound up here, sailed from some other continent, made its own pilgrimage.

A collection of longer, grey stones, like dolmens or phalluses, bend upwards. A complete circle. The canary yellow of your windows against the tar black house, the writing on the side of the house, John Donne. All have gone now, you, H.B now too, who died in 2018, and now a fundraising campaign to preserve the house and garden, and turn it into an artist’s residency, for others to go on pilgrimage. Shingle and distant sea. Railway sleepers as flower beds, as if travelling always in your destination, sleeping now for eternity. The garden, the opposite of Max’s poisoned dead suburban garden, sprayed non-stop with pesticides and filled with gnomes, in Jubilee (1978).

Gardens have become a luxury item in these days of the Covid-19 pandemic. Creating two tiers of people, those with and those without. To have a garden is to be able to go outside more than once a day. It seems as if nature, whom we did not realise we had banished to exile, has returned to us in lockdown, birds returning first to suburban gardens. In the still, less toxic, strange moment when time has appeared to stand still, the layers of all our selves have become available to us, like one of Jarman’s films. Those seeming anachronisms are simply the truth. It is we, too shallow in our everyday, clockwork lives, who forgot ourselves, historical layers of ourselves. Perhaps our collective sickness will prove to be the same epiphany that Tilda Swinton described Jarman’s illness as being for him.

In the garden, a wooden iron circle attempts to pierce the sky, to go into battle with it, during the day, and at night, to hook the stars. Echoes of the Buddhist protective bamboo forests surrounding temples[2], yet these are dead trees, unable to protect, when the plague has already entered. However, their original intention was to mark, and thereby protect the plants when they were subterranean in Winter. The dead protect the living. Consider this. He could no longer protect himself, but he could protect that which was still to emerge, help it on its way, to grow in darkness. Subterranean cine-children. Apart from the shades of green, yellow is the most brilliant colour, golden, the windows and the gorse. Your winter garden and the eyes of your house, shine golden.

Rainbows on my lens, prismatic, as light moves through the glass, lens flare. Light brown ferns. And various metal structures, to bring the energy, the electricity outwards, to the rest of the country. Energy source. The fences continuing on and on for miles, beside your house. Danger. No entry. The zone. Russet growth of bushes erupt from the pale shingle, salt. The wooden poles of the electric wires hanging between. Passing their currents along. It doesn’t have the Monet-like profusion of flowers of before, but it is a winter garden and a dead tree with holes stands opposite the doorway. Not the reds and yellows and oranges of a distant summer. The poppies, or even the white flowers of later. The valerian, crocuses, rosemary, daffodils, California poppies, burnet rose, the pinks of thrift, saxifrage, campion, purple iris of the past are gone or invisible. But there is yellow, of gorse. The shingle has lost its rippling concentric circles. Raked. An iron circle emerges from the shingle, as if a new planet, or a setting sun. Or a fallen satellite dish, no longer capturing signals to bring in, digital video communication, and falling silent, like the acoustic mirrors down the road, no longer straining their concrete ears to listen for enemy signals.

Meanwhile the PROTEST! exhibition at IMMA, art created in one pandemic, sleeps in crates, wrapped, in limbo, unable to move because of another pandemic, waiting patiently to go to its next, postponed, exhibition in Manchester. His last film Blue (1993), which stood at the entrance of the IMMA exhibition, a film about death as well as blindness, is echoed now in life – there are many these days who are dying on camera, their family or friends, not allowed to be present, on the other side of a video call. We have all been dematerialised, transformed into binary code to render ourselves non-contagious. Film, video is a safety thing these days. Video is a condom is a mask. There have been 65,000 excess deaths in the U.K. during lockdown at time of writing. A government, too slow – too inept, indifferent or hubristic to act earlier. In the Covid-19 pandemic, the immunosuppressed, the elderly in care homes, BAME, key workers, are the queers in Britain now.

This pilgrimage of mine is about loss. Layers of loss. I return to his house after leaving, driving away, and then after half an hour, panicking, thinking I have lost my phone, left it as an accidental, megapixel gift from the future, an iPhone for Derek’s ghost to start filming with, a ritual gift for everything that has been given to me. On my return, his neighbour emerges from her house and after I explain, she offers to phone me. I hear the ringtone from the boot of the car, and camera bag unzipped, my phone emerges from a secret pocket. For a moment though we are all connected, part of the exchange of electricity and waves of this place. I cry while driving along the empty flat roads leaving for the second time. For Derek too, amongst others. I should not be making this trip, but instead getting a coffee and boarding a train to London to go see him speak at the ICA or the BFI. It is also very nearly the last journey I ever take, my eyesight letting me down in the failing light of the return journey, where for a split second of slow motion fear, a fear of life ending or never being the same again, I lose control of the car, and it slides across the road, before I regain control and emerge unharmed. This never happens, has never happened before, but it happened that day on the way back from this unreal visit.

White witch’s garden. Apothecary. Pharmacopoeia. Please come back next year.[3] The cottage as a residence for artists will once again breathe new life into the house and garden, like the two small birds nesting shortly after Derek died, as described by H.B., Keith Collins, changing the sense of the garden for him, from one of death, to life. The cycles of eternal return and resurrection of a garden.[4] And so I imagine Derek Jarman, waking the day after a storm, or one afternoon in bed wrestling with fever, dreaming of the artists who will inhabit his house in the future. He sees them enter his house from the garden, bringing in a freshly clipped rose, Rosa mundi, rose of the world, as they sit down next to his bed to create.

“I post a letter to you, dear reader, in a red Italian envelope in the little red pillar box at the end of the garden, and watch the postman collect it at four pm in his red van. Italian business envelopes are always red. URGENT, they say.”

‘Chroma’ Derek Jarman – Chapter ‘On seeing red’

Susan Thomson

Susan Thomson is a writer and filmmaker, currently directing Ghost Empire, a series of films on LGBTQ+ rights, funded by the Arts Council of Ireland, which follow constitutional challenges to British colonial anti-gay laws in various countries, including Singapore, Northern Cyprus, and forthcoming in 2020 on Belize. The films have screened internationally including at Anthology Film Archives, New York; Kashish Queer International Film Festival, Mumbai; Yale NUS, Singapore; Scottish Government, Edinburgh; CCA, Glasgow; Queer Asia Film Festival, SOAS; and INIVA, London, and were nominated for ‘Best International Film’ at MICGénero film festival, Mexico City. A new essay film, about the colonial echoes of the U.K. government’s handling of the Covid-19 crisis, also funded by the Arts Council of Ireland, will premiere on NVTV, Northern Ireland, later this year.

Susan holds a Masters in European Literature from Magdalen College, Oxford University, an M.A. in Modern Languages from Trinity Hall, Cambridge University and an M.A. from IADT in Visual Arts Practices, and was represented by WME, William Morris Endeavor, for a novel about Roger Casement. The Swimming Diaries, an artist’s book, has been exhibited and sold at Artbook @ MoMA PS1, New York, and is held in the collection of the Live Art Development Agency, London.

[1] Modern Nature Derek Jarman Vintage page 91 “Yet Prospect stood firm on its foundations, unlike the farm in Kansas. Without light or heat for the next week, I stared at the glittering power plant on the horizon and wondered if, like the Emerald City and the great Oz himself, my life and this cottage had been dreamt all those years ago in Rome.”

[2] “A trip to Japan …The Hokoku-ji Temple in Kamakura was the key to the garden at Prospect Cottage” Keith Collins Derek Jarman’s Sketchbooks Thames & Hudson Chapter 5 The Garden, Howard Sooley

[3] The Garden (1990) Derek Jarman

[4] Arena BBC 2 1991 Derek Jarman’s Garden https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cbGbT5uVUHQ&t=331s

Categories

Further Reading

Curating at IMMA, through a queer lens by Seán Kissane

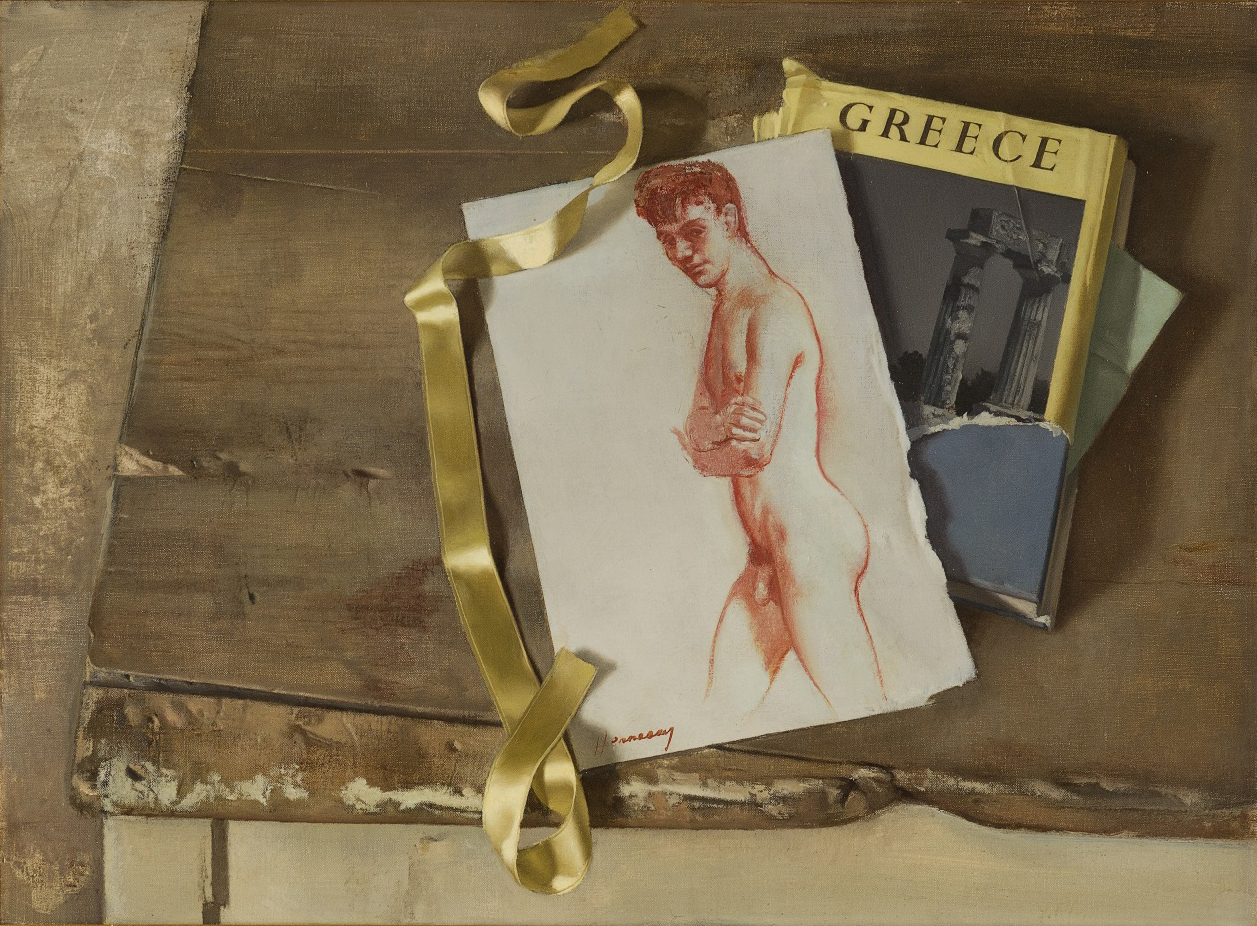

Seán Kissane, Curator of Exhibitions at IMMA, looks back at the exhibition on Patrick Hennessy he curated in 2016. Hennessy was one of the first Irish artists to depict his life as a gay man in the face of s...

A Vague Anxiety by Seán Kissane

The exhibition A Vague Anxiety at IMMA invited a range of emerging Irish and international artists to consider the macro and micro anxieties that inform a certain experience of the world today. In this essay...

Drawing from a lost well

National Drawing Day takes place today Saturday 16 May and although we cannot draw in the galleries this year IMMA is looking to explore our local and more immediate environment. In this article Barry Kehoe ...

At Home With Louise

To mark the tenth anniversary of Louise Bourgeois death, Brigid Mc Clean time travels to take another look at Bourgeois’s exhibition, Stitches in Time, shown at IMMA seventeen years ago.

Up Next

Curating at IMMA, through a queer lens by Seán Kissane

Thu Jun 25th, 2020