IMMA Talks Online: A Reflection on Dr Sara Ahmed’s lecture, ‘Complaint, Diversity and Other Hostile Environments’

Screen Studies Scholar Dr Zélie Asava looks back at this seminal talk on diversity work in educational and cultural institutions, exploring Sara Ahmed’s latest book on the lived experiences of minority groups where, despite a range of diversity and inclusion policies, she finds those who complain about discrimination still being cast as strangers or suspects, ‘persons to be interrogated’, and in response posits feminist projects of resistance.

——————————————————————————————————-

‘Complaint: a word can bring up a history. The word complaint derives from old French, complaindre, to lament, a lament, an expression of sorrow and grief, from Latin, lamentum, “wailing, moaning; weeping.’[1]

When reading her essays on feministkilljoys.com, I am always struck by the way Dr Sara Ahmed explores a word, an experience, a movement as indicative of wider social structures. Her lecture for IMMA’s Talks Online series explored histories of discrimination, drawing on the testimonies of those who have brought forward complaints about the institutional barriers they faced in universities whether as women, people of colour, disabled, LGBTQIA or all of the above, and the losses caused by this exclusion (as well as the imperial legacies which that exclusion protects). Ahmed’s talk took us on a journey from the local to the global, from the momentary to the systematic, which revealed the traces, as Edward Said puts it, of the imperial project in the everyday.[2]

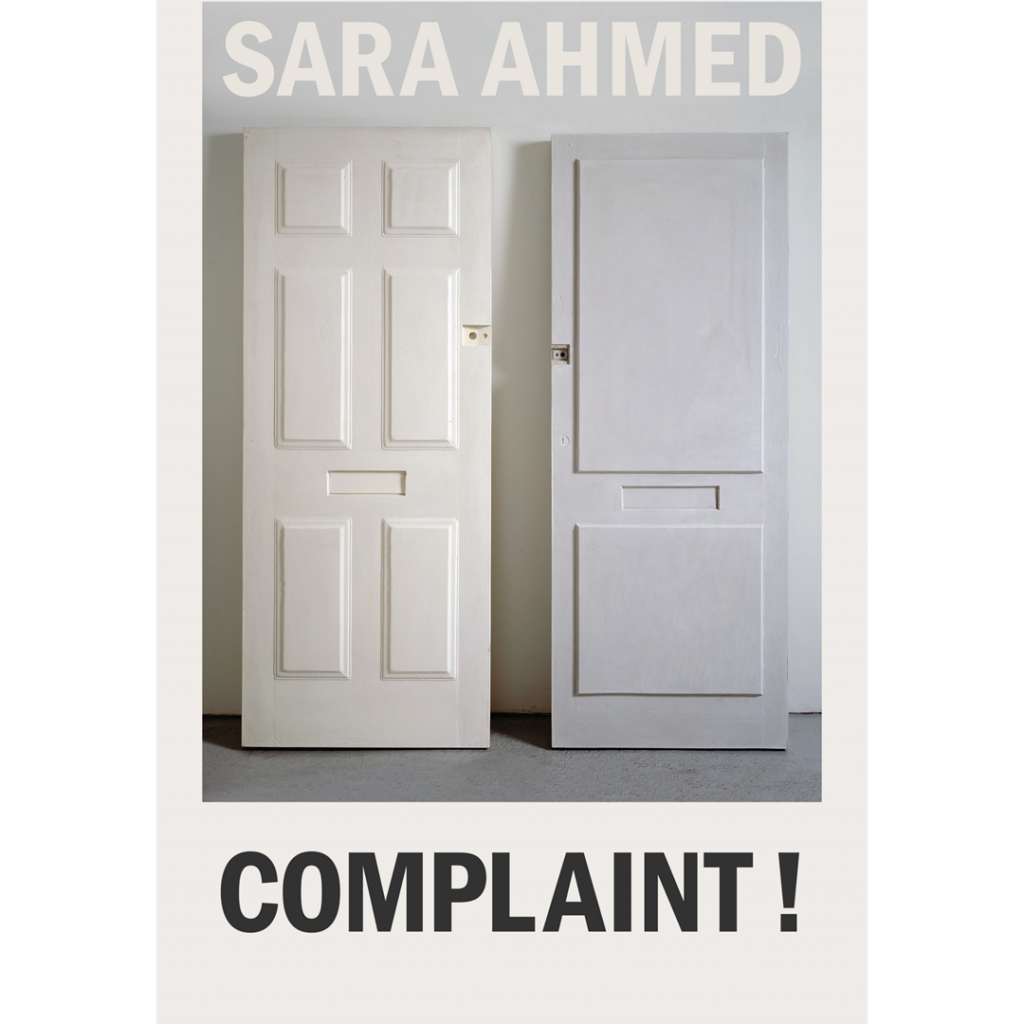

Sara Ahmed’s work philosophically interrogates gender studies, critical race theory, queer theory, power and postcolonialism. A prolific writer, her books include: 2019’s What′s the Use?: On the Uses of Use, where she considers utilitarianism and the potentiality of queer use; 2017’s Living a Feminist Life where she builds on feminist of colour scholarship to show how feminist theory is generated from everyday life; and 2014’s Willful Subjects where she interrogates relations between the will and wilfulness. Her live-streamed lecture was based on her soon to be published book Complaint!, taking us through the mechanics, technologies, compulsions and costs of complaint. Grounded in critiques of institutionalised diversity by feminists of colour, this book is a collection of stories gathered over a two year period with the participation of academics and students from across the world. As an Irish academic of colour whose work explores the intersections between race, gender, sexuality and representation in screen narratives, I was delighted to introduce her talk and chair the Q&A. Ahmed’s work resonates with mine in its interdisciplinary, intersectional approach as well as our common interest in ‘not only how others are viewed but the power relations at stake in the production of that view.’[3]

In the last year, complaint has featured heavily in our national narratives following the widening of the poverty gap driven by the Covid-19 pandemic, the death of George Floyd and the rise of the Irish Black Lives Matter Movement, as well as the critically awaited Final Report of the Commission of Investigation into Mother and Baby Homes. Yet, as I reminded the online audience, testimonies of racial harassment and violence were made public as early as the 1940s and dismissed,[4] while reports regarding systemic institutional abuse were submitted and filed away. Complaint was positioned as antagonism, ingratitude or self-promotion and embedded prejudices were obfuscated, entrenching the divisions which persist today.

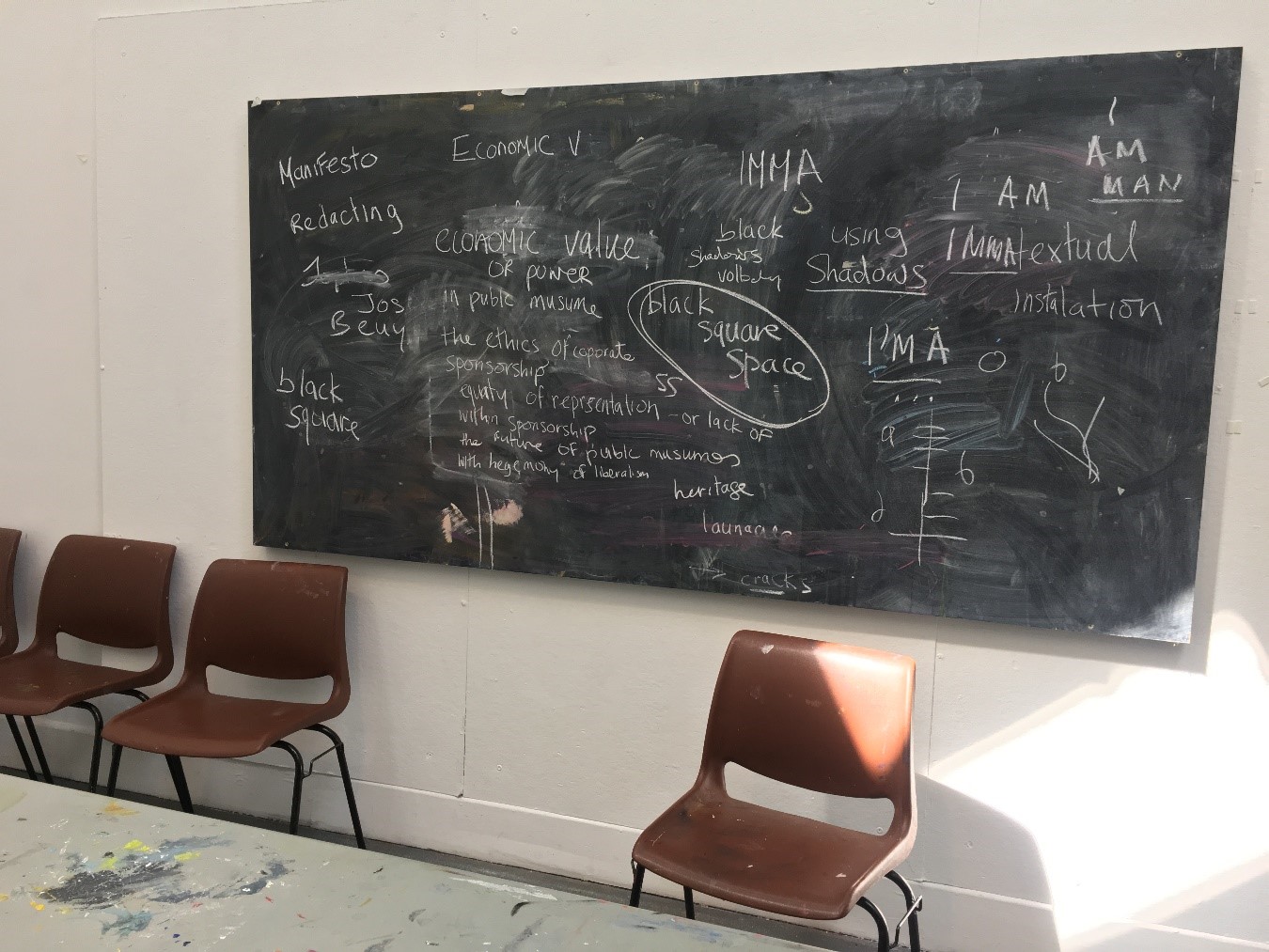

Critically reflecting on the role of ‘complaint’ within inclusion and diversity policies related to educational and cultural institutions, Ahmed showed how these spaces remain hostile environments despite or even through official policies on diversity and inclusion. In response, I asked Ahmed about what she refers to as ‘container technology’; where power is maintained through the restriction of the circulation of knowledge about those deemed Other, so that knowledge becomes a system of references in which the others are the objects, not subjects, spoken about, not spoken to. Ahmed presented ‘complaint collectives’ as a means of subverting asymmetric power relations and supporting complainants, observing that ‘it takes the work of a collective to spill complaints from their containers’.

Dr Philomena Mullen responded to Ahmed’s work in light of her own experiences of racism and speaking out, referring to institutionalisation and racialisation through personal testimony as a black mixed-race survivor of the Irish industrial school system. Ahmed noted how complaint teaches us about ‘what organisations enable; who they enable’ and the conditions of social membership. I was reminded of what Caelainn Hogan[5] calls the industrial-shame complex, whereby victims of institutional abuse were stigmatised and silenced, while institutionalisation was used as a mechanism for protecting narrow definitions of Irishness. Mullen’s comments on negotiating a racialised identity in an environment which is hostile to difference resonated with Ahmed’s positioning of complaint as diversity work, where the complainant’s otherness becomes the site of complaint, the cause of complaint, the performance of complaint. I thought of how complaint has become weaponised through the political valence of victimhood, as symbols of hegemony adopt what Lilie Chouliaraki[6] calls the ‘master’ signifier of victimhood, subverting discourses of power and violence through the neoliberal lens.

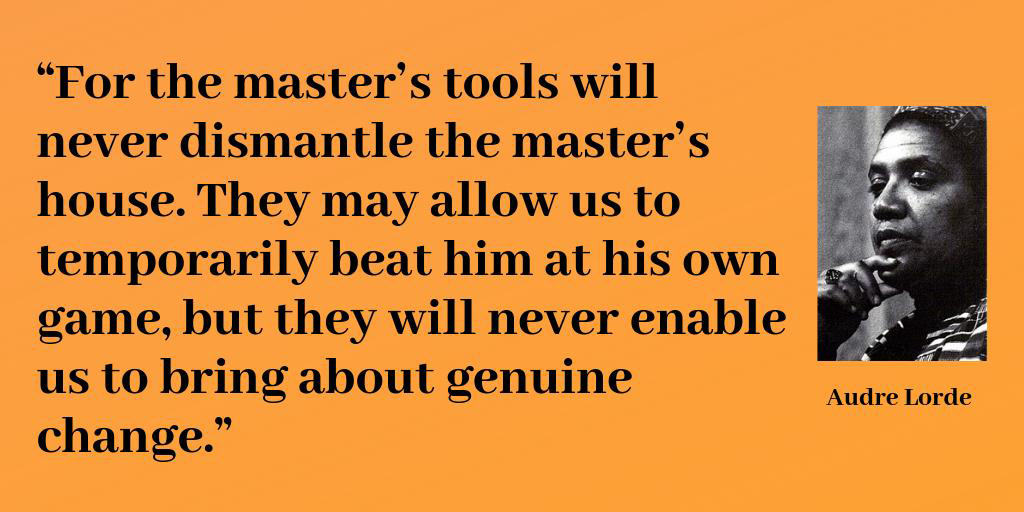

Dr Arpita Chakraborty explored issues of harassment, activism and intersectionality in her response, critiquing the lack of national frameworks to protect, support and empower victims of sexual harassment in both Ireland and India. Chakraborty discussed feminist recourses to sexual violence through reference to #LoSha, #MeToo and other feminist interventions. Ahmed examined why complaint is characterised as destructive rather than transformative or informative. She unravelled the pathologising of the complainant who, read as an institutional threat, is cast as disloyal, unpatriotic and ideologically removed, and who is subsequently physically removed. Coming back to complaint as pedagogy, Ahmed explored the architecture of the institution, with doors as symbolic of the barriers that stop some from progressing yet are imperceptible to others, that appear open but are ‘shut when you try to enter’. Referencing Audre Lorde’s observation that ‘the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house’,[7] Ahmed critiqued the ‘diversity door’ as part of the ‘institutional mechanics of the non-performative’; investigations of structural inequalities whose recommendations go unimplemented and become yet another trace of a complaint. I thought of Sartre, who coined the term ‘neocolonial’ to argue that the colonial system could not be reformed by a structure which was itself colonial.

In the third and final response, Dr John Wilkins explored how universities can work to decolonise their programmes and expand their employment practices in ways that support and respect academics and students of colour rather than continuing to reinforce hegemonic discourse through what Ahmed calls ‘coercive diversity’. Time and again, Ahmed drew our attention to the methodology of the institution which seeks to present discrimination as a private problem, a problem which ought not to exist and therefore is deemed not to exist. This is what she calls the ‘institutionalisation of diversity’ where ‘techniques to redress racism… can be used as techniques for concealing racism’.[8] Lorde’s words left their trace across Ahmed’s notes on ‘queer use’ and the evolving functionality of space, as she called for a new structure of reform, a new institutional architecture and a new technology of hearing. Furthermore, Ahmed explained, only through transformative ‘dismantling projects’ might cultural institutions begin to accommodate those they were not built to accommodate. And while our complaints may end up in the complaints graveyard, these shadows from behind the veil[9] can also return to haunt an institution: ‘complaints can participate in the weakening of structures without that impact being tangible.’

Throughout her talk, Sara Ahmed spoke to our need to transform understandings of complaint and the complainant and to resist ideologies, policies and practices designed to silence and stigmatise. She listened with care to stories of complaint and acknowledged the hard road ahead. But she also provided hope through models for how we might find ways to push through systems resistant to complaint in order to achieve lasting structural change, and to become agents of that change given that, as Ahmed notes, not only is the personal political the structural is also personal.

[1] Feministkilljoys, Diversity Work as Complaint, 2017.

[2] Said, Edward. Orientalism. London: Routledge, 1978.

[3] Feministkilljoys, Diversity Work as Complaint, 2017.

[4] Brannigan, John. Race in Modern Irish Literature and Culture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2009.

[5] Hogan, Caelainn. Republic of Shame: How Ireland Punished ‘fallen Women’ and Their Children. London: Penguin Books, 2020.

[6] Chouliaraki Lilie. “Victimhood: The Affective Politics of Vulnerability”. European Journal of Cultural Studies. Vol. 24 (1), 2021, pp. 10-27.

[7] Lorde, Audre. “The Master’s Tools Will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches. 7th Ed. Berkeley, CA: Crossing Press, 2007, pp. 110-114.

[8] Feministkilljoys, Diversity Work as Complaint, 2017.

[9] DuBois, W. E. B. The Souls of Black Folk. New York: New American Library, 1969.

Categories

Further Reading

Ideas of Queer Use by Sara Ahmed

We look forward to hosting Sara Ahmed at IMMA in February 2021. In the meantime we invite Ahmed to connect with IMMA’s online community with a short text that introduces the research threads that are so syno...

Stories of Hospitality

In association with the Visual Voices Project 2021 presented at IMMA, we invited Julie Daniel, the coordinator of the DCU University of Sanctuary Mellie programme with Veronica Crosbie, to share her insights...

El Lissitzky: The Artist and the State

On the approach of the centenary of Ireland’s Easter Rising and the subsequent establishment of the new Republic, IMMA is pleased to announce the exhibition, El Lissitzky: The Artist and the State.

Up Next

IMMA International Summer School, ART AND POLITICS #3 containment

Sun Jun 6th, 2021