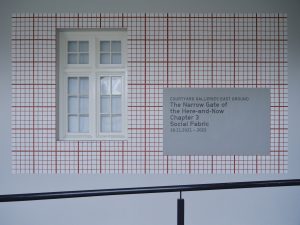

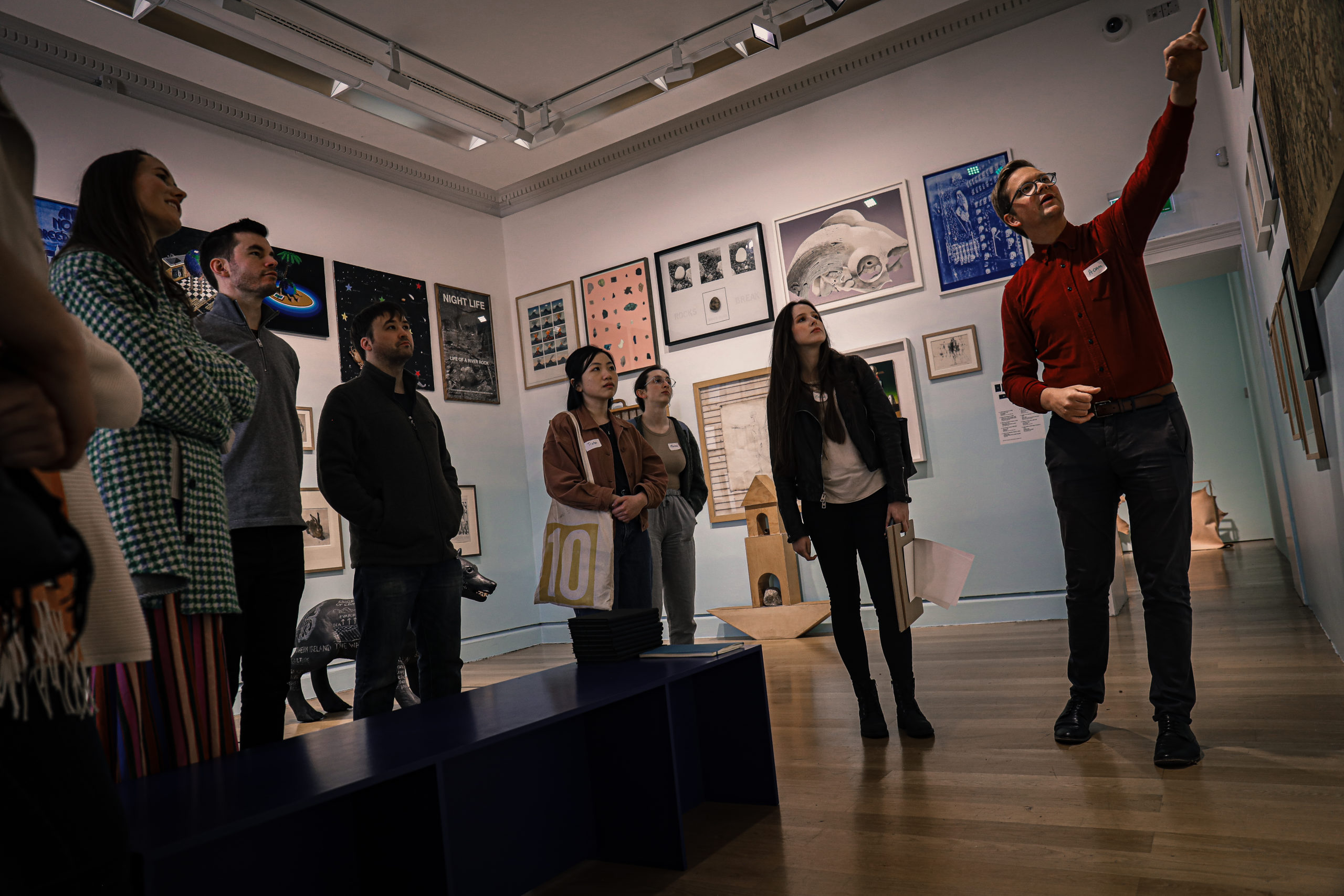

Caroline Carlsmith participated in Dr. Brian Castriota’s 2021 seminar on the conservation documentation of time-based media (TBM) art at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Facilitated by Castriota’s work with IMMA as TBM Conservator, students created documentation for a TBM artwork held in IMMA’s collection.

TBM is a capacious category that encompasses any artform which unfolds to the viewer over time, including growing collections in contemporary art museums such as moving images, interactive art, kinetic sculpture, performance, and installation. This text describes Carlsmith’s personal experience of documenting Dennis McNulty’s installation artwork ‘I reached inside myself through time’ (2015) in the context of her practices as both a conservator and an artist. Her engagement with the work relates to ideas of authorship and authenticity within contemporary art conservation.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

More than one maker

This book has two authors – Olaf Stapledon, Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future

Olaf Stapledon’s 1930 science fiction novel Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future details a history of the future of humankind over tens of millions of years. Part of its conceit is that the book was apparently written by two authors, each occupying a different historical time. One author is “contemporary with [the book’s] readers” who are themselves contemporaries of Einstein. [1] The other is “an inhabitant of an age they would call the distant future.” [2]

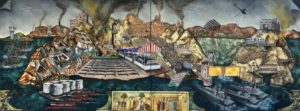

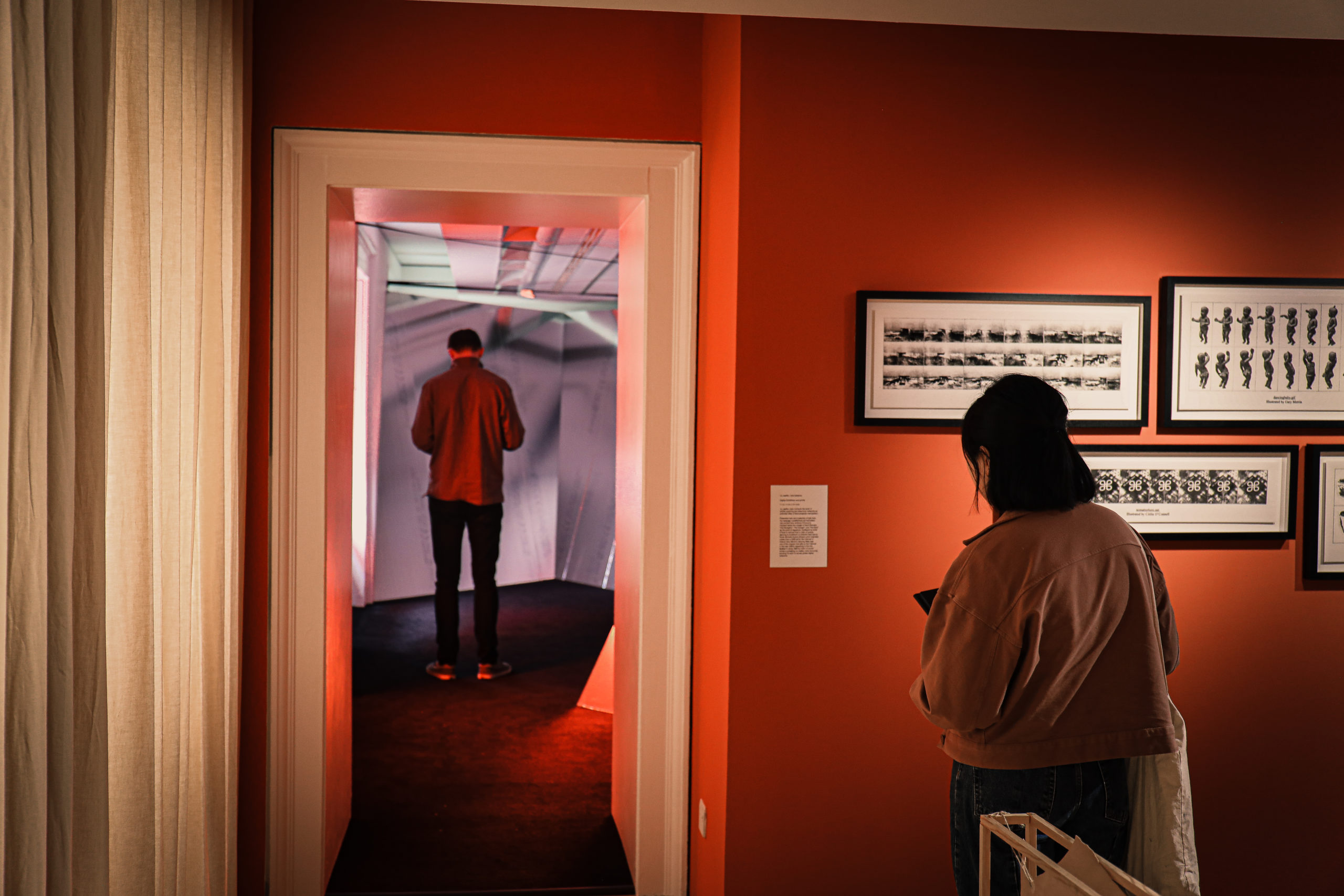

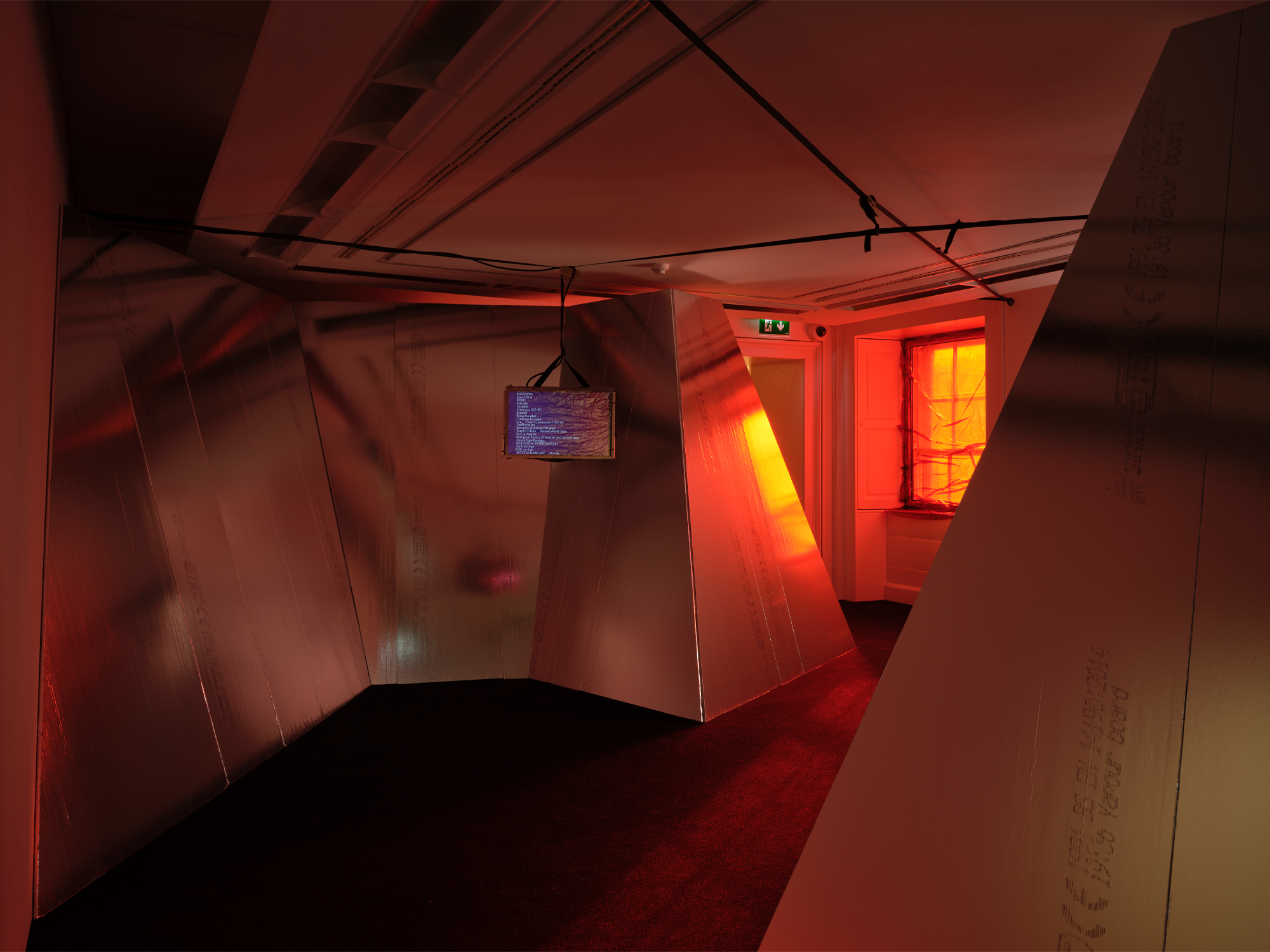

To write a text, as to make an artwork, is always to reach across time and space. Stapledon’s novel and its sprawling timeline are referenced within Dennis McNulty’s installation artwork, I reached inside myself through time (2015), part of the collection of the Irish Museum of Modern Art. Entering a room filled with reddened daylight and reflective, tilting structures, viewers of McNulty’s work encounter a suite of sounds and moving images that seem to come from both the past and the future. On a modified LCD screen suspended on ratchet straps from the ceiling, events and eras from Stapledon’s two-billion-year timeline scroll bilaterally from the horizon of the near-present. Simultaneously, an edited acapella recording of Norwegian pop band A-ha’s 1985 hit The Sun Always Shines on T.V. emanates from rigid architectural elements transformed through vibration into speakers. “I reached inside myself through time,” the voice sings. “Give all your drifting distant mirrors, all your love, inside my mind. / Believe me, / the mirror’s sending me through time.”[3]

Like the last men of Stapledon’s novel reaching to the first, the figure of A-ha lead singer Morten Harket is also reaching from one world to another. On a small screen attached to the reverse of the larger one, a flickering drawing of Harket glows through the metallic film of an anti-static bag, giving the animation a subtle mirrored quality. The shifting image, run by a microcontroller called an Arduino Uno, resembles the famous 1985 Take On Me music video (another A-ha hit) animated by tracing individual frames of a film or video using a technique called rotoscoping. In the music video, Harket moves between photographic reality and an animated, monochrome world, reaching through the drawn windows of a comic strip to travel between it and the three dimensions that his beloved inhabits.[4]

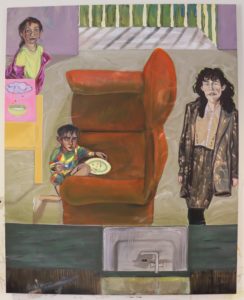

Kavanagh

I have not experienced the installation in person, so I reached through my own windows towards this work. As a graduate student focused on the conservation of contemporary art and time-based media (TBM) art, I studied and documented McNulty’s piece as part of a partnership between my university and the Irish Museum of Modern Art (IMMA) facilitated by TBM Conservator Dr. Brian Castriota. I know the work remotely and asynchronously: as the initial installation in Lofoten, Norway in 2015; as it was installed on two different occasions at IMMA, in 2016 and 2021; and as an installation in the future, to be potentially created even after McNulty is gone. Without knowing the work experientially, I know it intimately: I know the source material, the file formats, the parameters which the artist considers important and the ones that might shift, which aspects of the experience are intrinsic to the work and which are incidental. Or, I think I do.

In addition to my conservation studies, I am also a practicing artist. I make artworks of the type that I am most drawn to conserving – complex installations with interactive, performative, sculptural elements, often including electronic media. One thing I am drawn to in these types of artworks is the way in which they are “dormant” when not on view. Such “dormant” works may only take a physical form when they are on view, and this makes them uniquely vulnerable among artworks. To understand what makes these works special, consider an oil painting or bronze sculpture in a museum storeroom. These artworks remain physically intact both on and off display, whereas an installation artwork is disassembled when the exhibition is over, and only parts of it might be retained. Thus, documenting the work thoroughly is imperative for its conservation, for its existence in the future.

To the extent that I have experience conceiving of and producing such artworks, I hope I am well equipped to conserve them. Yet, as I documented McNulty’s artwork, I also wondered how my own habits of making might become hazardous to the works I conserve through the blurring of my own aesthetic preferences with those of the artist whose work I am caring for.

Conserving TBM artworks

The practice of art restoration is probably as old as artmaking, but the relationship – and growing distinction – between artists and conservators has shifted over time. While historically artists often restored their own works or the works of others, current conventions in the field distinguish between the “creative” work of artmaking and the “scientific” work of conservation. This distinction attempts to reassure the public (not to mention the artist and the conservator) that the artist will remain the sole author of the work, and that the conservator will protect it without making changes that would produce a meaningfully different artwork. Ideally, contemporary conservators are “objective” in their interventions, faithfully reproducing the artist’s intended effect through no “artistic” work of their own.

Yet as forms of what is publicly understood as art shift, so too do the responsibilities of the conservator, and this shift is particularly evident in the conservation of TBM art. TBM artworks are works that include duration as a dimension, revealing themselves to the viewer over time. This seemingly simple definition applies to a diverse range of forms, including film and video, performance, installation, internet-based art, software-based art, sound art, bio art, interactive art, and artworks that incorporate material change into their conceptual structure. These new artforms require new conservation frameworks, particularly because they often necessitate partial or full re-creation to be seen. I will refer to such (re)creation events as “instantiations.”

Increasingly, conservators like myself understand our work, not as scientifically objective, but from a situated perspective that attempts to account for our own identities and biases. Laying aside supposed universality or neutrality, many now see conservation as what conservator Hélia Marçal has called a “knowledge-making, situated, practice.”[5] Understanding our positions as specific to place, time, race, class, gender, education, belief system, and other intersectional identities requires a conservator to relinquish any claim we might have made to objectivity. But if we are not objective, how do we avoid being creative? How do we avoid acting as an artist?

Documentation, authorship, and authenticity

Documentation of an artwork can take a wide variety of forms. It might be textual, photographic, audiovisual, three-dimensional, anecdotal, embodied, crowd-sourced, schematic, thick or thin. It is, at best, ongoing, polyvocal, and self-reflexive. The aim of documentation is to gather instructions and other key information for installing artworks in the future and ensuring their preservation across time. Often times these may be manuals, sketches, reports, questionnaires, photographs or videos stored in museum archives and offices. Regardless of form, careful documentation is crucial for institutions like IMMA that are collecting artworks that do not carry their own material record. For Castriota, “an object or entity is safe-guarded not by discovering and protecting its ‘true’ essence, but rather by investigating and documenting how significances are negotiated and vary among diverse audiences, in different settings, and through time.”[6]

Many arguments about whether an artwork has been authentically instantiated hinge on the idea of artistic intent: a slippery concept predicated upon the assumption that an artist’s intentions are static, knowable, and paramount. Yet as has been widely documented, many artists change their described intentions for their works over time, with a particular trend towards greater openness to conservation interventions later in an artist’s career. With TBM artworks, the artist sometimes makes changes when a work is re-installed, as has been the case with I reached inside myself through time. Such changes can highlight the properties of the work which are unalterable, and which are variable, making the essential qualities of the artwork clearer.

McNulty has made a variety of changes to I reached inside myself through time from instantiation to instantiation. Some of the most noticeable of these include the installation architecture, which was covered with Easygrow Eco Silver White Lightite film in the first instantiation (Lofoten, 2015) but made of metallic plasterboard in subsequent instantiations (IMMA, Dublin, 2016 and 2021-22). Similarly, the windows were painted with red oil paint in Lofoten but later covered with red plastic film at IMMA. These differences reflect both site-specificity and a certain mutability in the work, which is not uncommon for installation art.

Questions about artistic intention and authority are complicated further when more than one author is concerned. For example, a work may have been produced collaboratively by an artistic pair or collective, and the artists might have different ideas about what the work is and how it should move forward into the future. Even when artworks are produced within the studio of a single artist, studio managers, studio assistants, and contracted fabricators might all have a substantial hand in the production of the work and may well have made aesthetic decisions that strongly influenced the work’s direction. When the work has left the studio and entered an institution like IMMA, conservators, who are often tasked with direct interventions into artworks as a part of their caretaking, must remain wary of how their interpretations and actions impact the way it will be experienced and understood.

The authenticity of an artwork can be called into question when there is a loss of material components and it is recreated with new materials (as with many TBM artworks), particularly when this is done without the direct involvement of the artist. In some instances, changes imposed by a curator or conservator might cause a work to be poorly instantiated or even fail to instantiate it completely, but at other times aesthetic interventions into artworks by other agents might even cause the instantiation to be an artwork of its own with new or dual authorship, rather than an instantiation of the original artist’s work alone. It was this trap I was hoping to sidestep as I worked to document I reached inside myself through time.

Documenting I reached inside myself through time

When I began documenting I reached inside myself through time, I noticed that, rather than beginning by exploring what information I could initially access about the work itself, I chose to start with the text which had been sampled in the work: Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future. This move felt natural to me, but I was also suspicious of how natural it felt. When I make installations in my own practice, there is always a text, if not several, buried in the project. It seemed to me that McNulty, through his quotation of Last and First Men and The Sun Always Shines on T.V., had, at least in this work, made a similar move. Another conservator might not have decided that the best way to approach this documentation was to begin by spending weeks reading a dense and potentially irrelevant science fiction novel written nearly a century prior. Particularly since it is only the Stapledon’s timelines that are actually quoted in McNulty’s work. There was no obvious reason to begin with that text – one might have begun with a survey of A-ha’s discography, or with a video walk-through, or a 3D rendering, or a wiring diagram, all of which would have resulted in very different documentation, potentially influencing future instantiations of the piece.

After I had made my initial attempts to document the installation, I had the opportunity to interview McNulty about aspects of his work I did not yet understand. Artist interviews are an important tool for conservators of contemporary art, and the interview helped me mitigate the influence of my personal biases in my documentation. I told McNulty I had read Stapledon’s novel, and he laughed and said I had gone “beyond the call of duty.”[7] In my own artistic practice, many of my works have dealt with literary figures – for years I made artwork about the nineteenth-century American poet Walt Whitman, who also reaches through time in his poetry. In this way, it was natural for me to document the installation as a text. McNulty, however, comes from an audio engineering background. He was making moves with sound I did not initially understand, nor would I necessarily have done so if he had not explained them to me when I interviewed him. McNulty was using impulse response recordings, which he described as “like a sonic fingerprint of a particular space.”[8] To do so, one makes a loud bang like a popping balloon and records the sound. This activates the resonances in the space, and the resulting impulse recording can then be processed by a piece of software called a convolution reverb plugin. Play another sound through the plugin, and it will apply the reverb of that particular space. As a part of I reached inside myself through time, McNulty had made impulse recordings in different spaces around Lofoten, including a concrete bunker formerly occupied by Nazis, traffic tunnels through mountains, an underground sports hall, a dry dock, and a community space.

In the audio component of the installation, Harket’s voice is processed to sound as though he is passing through these spaces. As McNulty readily acknowledged, for most people these audio qualities are subtle enough to work on a subliminal level, but the differences in reverberations would be evident to the trained ears of anyone who recorded music, which I do not. Knowing that this information was present in the work prompted me to wonder how a sound engineer might have approached documentation – no doubt quite differently than I had.

When I interviewed McNulty about I reached inside myself through time, we were joined on the Zoom call by Castriota, along with Claire Walsh, an Assistant Curator in IMMA’s Collections department. After McNulty finished patiently answering my questions about obsolete operating systems and configurations of ratchet straps, he took a moment to thank Castriota for a talk he had recently given, which McNulty had accessed as a recording. McNulty was excited about Castriota’s thoughts on the conservation of TBM artworks, which had prompted McNulty to recast his own work as a performance rather than an object. Listening, I was reminded that there were many ways an artist and a conservator might influence one another, and the works in both of their pasts and futures.

Conservation without objectivity

Regardless of how much we might deny it in deference to the fantasy of scientific objectivity, conservation documentation is a creative act. While artists and conservators may have been separated by academic systems and the current understanding in European and European-dominated cultures of what is appropriate conservation intervention, we are not as separate as we might appear, just as I am not separate from myself.

Categorical titles such as ‘author’ or ‘artist’ disguise a distributed network of actors with a variety of goals who, through their various forms of labor or influence, together give rise to an instantiation of an artwork. Given that an artist might be separated from a conservator blurrily if at all, and that artistic authorship is commonly more decentralized than is broadly acknowledged, any of us – wearing any hat – who hope to care for an artwork should try to remain cognizant of how our actions might shape the futurity of that artwork. But, as objectivity and perfect knowledge are idealizations unavailable to us, we also cannot allow ourselves to be paralyzed by the imperfections of our attempts to reach through time. All we can do at this time is give ourselves permission to try, and to certainly fall short, and to try again, to assist in the continuous co-creating that is care.

……………………………………………………….

References

[1] Olaf Stapledon, Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future & Star Maker, (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1968), 13.

[2] Stapledon, Olaf. Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future. New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1968.

[3] Dennis McNulty, I reached inside myself through time, 2015, Texts from Olaf Stapledon’s timeline for Last and First Men: A Story of the Near and Far Future, an acapella recording of Morten Harket’s vocals for The sun always shines on TV sourced on-line, True Type (digital) rendering of the Futura font by Paul Renner, high resolution impulse response recordings made in various spaces in the Lofoten islands, Reaper DAW with convolution reverb plug-in, Feonic audio-actuators, stereo amplifier, 2 Raspberry-Pi computers running Raspbian, openFrameworks open source toolkit, programming, modified LCD screen, Arduino Uno with 2.8″ TFT display, anti-static bag, aluminium profiles, cables, cable glands, nuts, bolts, screws, wood, webbing, ratchet-straps, plasterboard, plastic window film, black carpet and adhesive, Dublin, Irish Museum of Modern Art.

[4] A-ha, “a-ha – Take On Me (Official Video) [Remastered in 4K],” YouTube, January 6, 2010, Video, 4:04. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=djV11Xbc914.

[5] Hélia Marçal, “Situated Knowledges and Materiality in the Conservation of Performance Art,” ArtMatters International Journal for Technical Art History, Special Issue 1 (2021): 56.

[6] Brian Castriota, “Variants of Concern: Authenticity, Conservation, and the Type-Token Distinction.” Studies in Conservation (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2021.1974237. pe-Token Distinction.” Studies in Conservation (2021): 9, https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2021.1974237.

[7] Dennis McNulty, Artist Interview, December 1, 2021.

[8] Dennis McNulty, Artist Interview, December 1, 2021.