Understanding Hilma. A life dedicated to spirituality in art

By Leda Scully, Visitor Engagement Team, IMMA.

‘But no, she’s abstract, is a

bird

Of sound in the air of air

soaring,

And her soul sings

unencumbered

Because the song’s what

makes her sing.’

Fernando Pessoa

At the time of her death, the Swedish artist and mystic Hilma af Klint (1862 – 1944) left behind a body of work comprising 1,200 paintings, numerous sketchbooks and 26,000 pages of journals. She stipulated in her will that the work should not be seen for twenty years after her death, but in fact it was forty-two years before it was exhibited for the first time, in the 1986 show The Spiritual in Art: Abstract Painting 1890 – 1985, curated by Maurice Tuchman in L.A . Record numbers attended that show and audiences were reportedly stunned by this unheard-of Swedish painter whose work had remained unseen for so long, and who, it transpired, may have painted the first ever abstract paintings in Western art – quite a few years before Kandinsky.

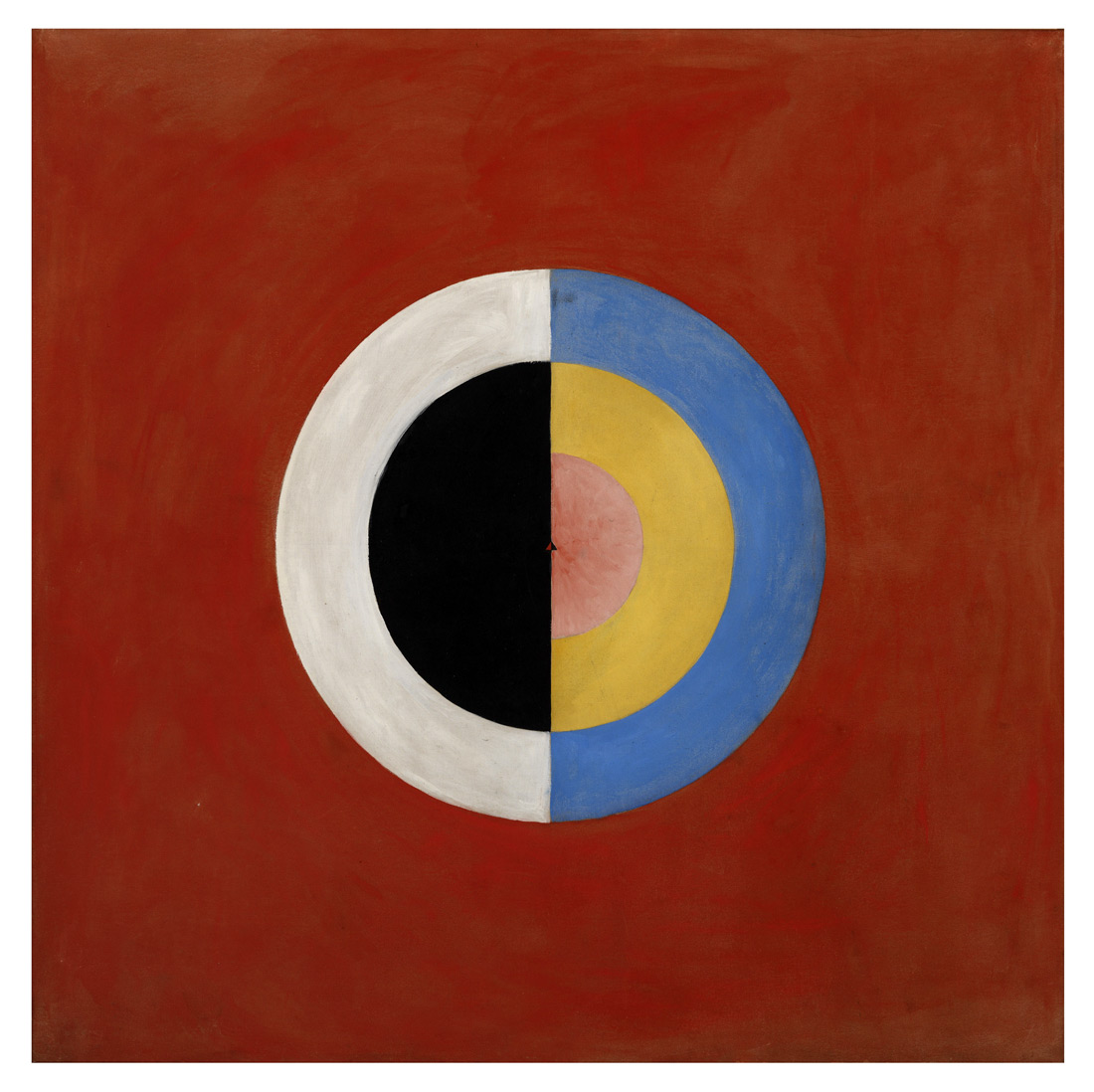

This is the second time Hilma af Klint’s work has been shown in IMMA . The first was in the landmark travelling show ‘3x Abstraction,’ which drew parallels between her and two other key female abstract artists – Emma Kunz and Agnes Martin . In 2005, John Hutchinson also curated a show of her work in Dublin for the Douglas Hyde Gallery, in which the image above (titled ‘The Swan, no 17’, 1914/15) was shown. So who was Hilma af Klint, and how did she discover her style? Born in Stockholm in 1862, her family naval-officer family had a long history of map making, mathematics and science. Fascinated by Spiritualism from an early age, she was thought by her family to have the gift of prophecy. Unusually for a woman of the time, she attended university and received an academic training in painting, even maintaining her own studio for more than a decade in the centre of Stockholm (in the same building that housed the gallery Edvard Munch showed in).

During her university years she met and formed a group of four other women called ‘De Fem’ (the five) who were interested in Spiritualism and and Theosophy. They met once a week to experiment with mediumship and automatic writing (examples of which are included in this show), pre-dating the Surrealist practice by decades. To put this in context, it was much more common – even respectable – for people to experiment with the occult at the turn of the 19th Century. New religions such as Theosophy and Anthroposophy , which blended new Scientific discoveries with a belief in ‘Higher powers,’ arose to fill the place of organised religion, and proved very influential in artistic circles. Yeats, Mondrian and Kandinsky were well-known proponents of these movements. Stockholm too would have seen the leading neo-spiritual figures such as Annie Besant and Rudolph Steiner give lectures which Hilma Af Klint attended. (Later in her career Rudolph Steiner famously snubbed Mondrian to visit Hilmas studio rather than his, where he told her that no one should see her work for fifty years).

Hilma herself was a strong-willed, formidable character with an inquiring mind. Interested in science, mathematics and the natural world, she was vegetarian and a physically small woman of 5 ft (significant when we look at how large some of her paintings are) with piercing blue eyes. In 1904, during a meeting with De Fem, Hilma af Klint received an order from a spiritual entity that she was to create paintings on the astral plane. ‘I was to place myself under the direction of the Guru who produced symmetrical, spontaneous, astral pictures through me. It was not the case that I was to blindly obey the High Lords of the Mysteries but that I was to imagine that they were always by my side.’ She began this work into uncharted spiritual and artistic territory finally in 1906, making thirty-seven paintings.

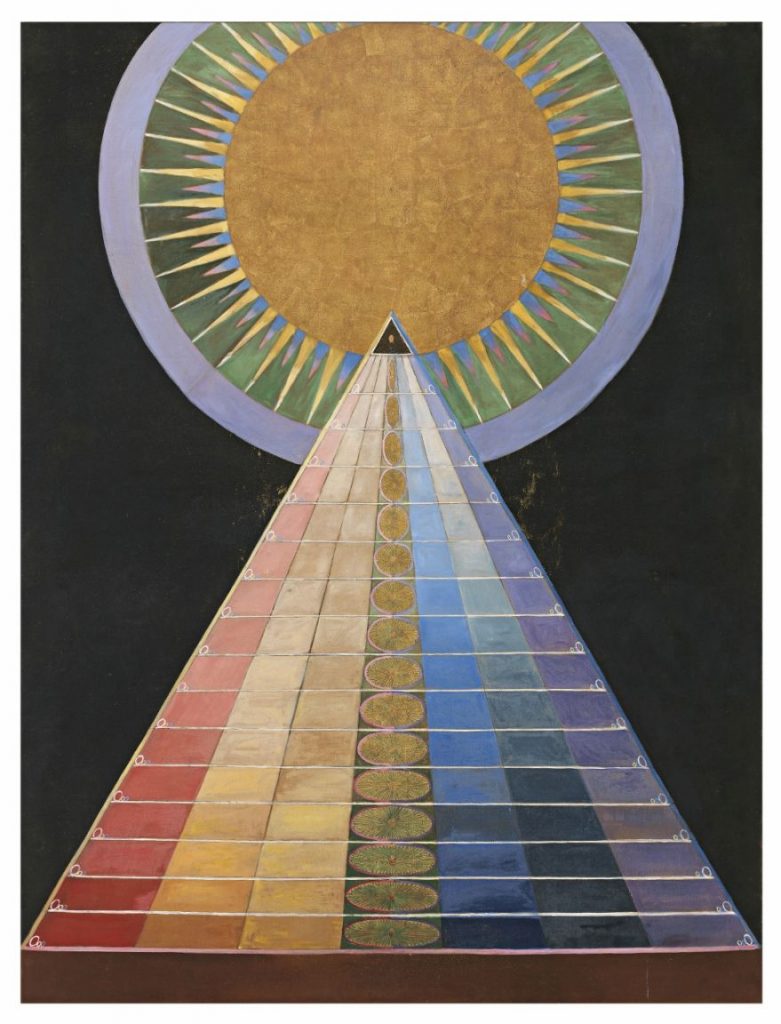

Then, in 1907 she began ‘The paintings for the Temple’, some of her best-known work. Comprising 193 works, these were series within series, numbered and in sequence. 111 of them were painted within a year and a half, which meant she finished one every three days. These were made under total mediumship, whereby she was unaware of what she was doing, working ‘with great force’ and without any corrections. She collapsed from exhaustion at the end of the last one. Following this there was a break of four years where she cared for her dying mother. Then in 1912 she took up the mantle again to complete the series, painting three more huge 11-foot paintings titled ‘Altar paintings’ (pictured above, ‘Altarpiece, no. 1, 1915’, currently on view in IMMA).

For the rest of her life, Hilma Af Klint was to continue working as a conduit for the spiritual in painting. From her work and meticulous notes we can discern a distinct iconography: pink for spiritual love, red for physical love, blue for female and yellow for the male. Green symbolised perfect harmony while overlapping discs were unity. The letters ‘Wu’ symbolised the dual relationship between matter and spirit and ‘ao’ signified spiritual evolution: “The idea is to present a core from which evolution starts in rain and storm, lightning and tempest. ao can also stand for Alpha and Omega: ao the beginning and the end of a day’s journey, ie. a period of development in both climbing down into matter and rising up to fully clear consciousness of life’s content” (Hilma af Klint).

Her ultimate goal was unity for mankind, but in creating this work she sacrificed a career as a professional artist, and a ‘normal’ family life. Aside from the esoteric content of her work the problem of her gender too made the idea of being accepted by her contemporaries impossible. Regardless of a woman’s artistic talent, whatever they produced was regarded in Sweden as ‘mere women’s work’, and so she worked in secret. In doing so she was able to build up this abstract iconography without coming under fire from her contemporaries, and without them being at all aware of her artistic breakthroughs. In a strange quirk of fate that plays out to this day over a hundred years later, Hilma actually exhibited alongside Kandinsky in 1914 in the Baltic Exhibition in Malmo. Here marked her last foray as a professional academic painter, a woman showing figurative work in public, but painting abstracts in private. Kandinsky, the self-proclaimed first abstract artist, had no idea of the existence of this woman who ended up usurping him in his endeavours to be the first abstract painter in history. And now here they are exhibited together again, in ‘As Above, So Below’, on view till August 27th 2017.

Categories

Further Reading

CVLTO DO FVTVRV. ‘Wilder Beings Command!’

Artist Stephan Doitschinoff, currently exhibiting at IMMA as part of As Above, So Below: Portals, Visions, Spirits & Mystics, will return to IMMA this July to present the CVLTO DO FVTVRV.

Out of Body. Susan MacWilliam

Susan MacWilliam was invited by IMMA to respond to their exhibition, As Above, So Below: Portals, Visions, Spirits & Mystics, and to work with Alice Butler and Daniel Fitzpatrick to develop a screening.

Up Next

Ellen Altfest. The Relationship between Artist and Model

Wed Aug 16th, 2017