Thinking of the Network by Rebecca O’ Dwyer

A while back, in Lidl, the cashier was so fast in scanning my things I barely had time to open my wallet before she was done. I have never seen anything like it. Unnaturally quick, it was obvious her hands far exceeded the demands of any computer tick-ticking behind the scenes. Was it enjoyable for her, I wondered, to move quite so fast? My body was pushed into reciprocal action, and it was anything but.

Lately, I have been thinking a lot about speed. Everyday occurrences like this one give the impression that, mediated and monitored by technology, daily life is becoming much faster. Nearly all of us now participate in this acceleration — most visibly, through incessant smartphone use. Emails and messages should be replied to immediately, when earlier they only could. Goods and services can be accessed instantaneously; previously, we needed the time to go somewhere else. The human body has not changed. But, thinking of the Lidl cashier — along with, for example, Amazon warehouse workers and Uber drivers — our bodies are clearly being brought instep with a new pace. However technological progress involves increasing automation, meaning some of us will likely struggle to keep up.

Evan Roth, Red Lines, Commissioned and produced by Artangel, Supported by Creative Capital, Web Source

This process of acceleration, as Wolfgang Tillmans’ audio work I Want to Make a Film (2018) makes clear, is largely incomprehensible. Presented at IMMA, the aim of the work lays the ground for another one: a visualisation — a film — detailing how we reached a point in which we cede power to smartphones (read: technology) to do just about everything. Tillmans is astounded at this situation: now, he observes, we hold super-computers in our hands, a prospect unthinkable back when the first hulking PCs came along in the 80s. But the film never gets made; instead, Tillman’s leaves a set of unanswered questions. What does technological change do to the brain, he asks or to photography? How have chips gotten smaller, as technological processes grow lightning fast? How is that even possible? Most listeners will share in his confusion. While created and used by humans, it seems technology represents a technological complexity unthinkable, and arguably even indifferent, to us.

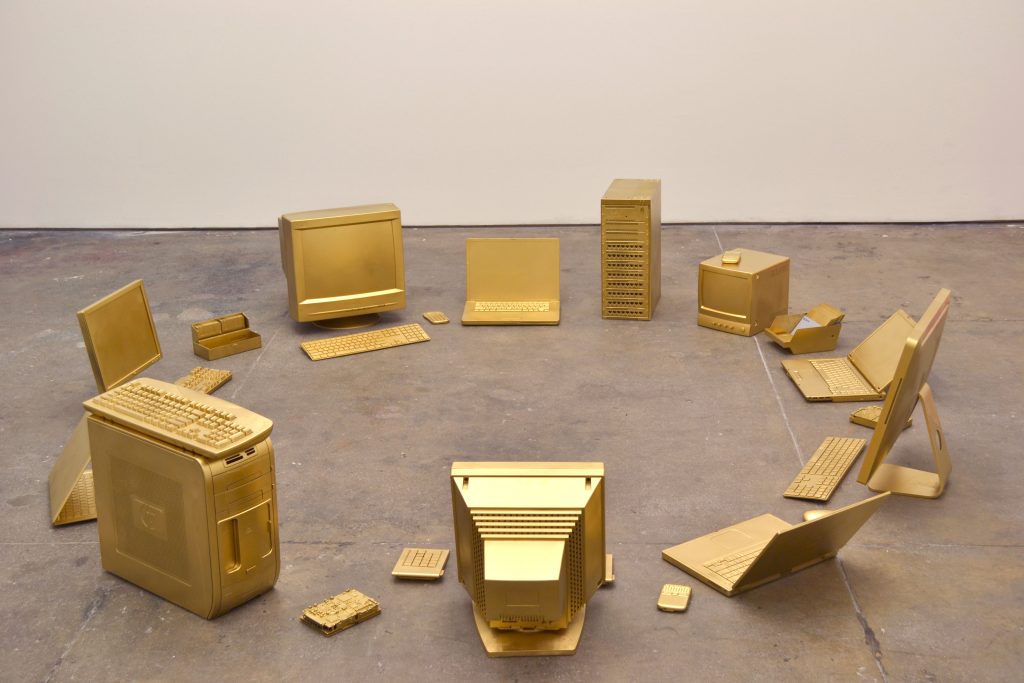

Contemporary art, like all other fields, has shifted in line with technological change, taking place as much online as off. Dependent on worldwide communication and visibility, this is probably par for the course. Artists’ Instagram feeds draw gallerists and curators, while more and more art is being made and commissioned for online viewing alone. The recently opened Dublin gallery Berlin Opticians, for example, is not a physical space, but instead displays and promotes its artists online (after exhibiting it for a brief period in a traditional gallery space). In this, the gallery navigates the enduring problem of Dublin’s sky-high rents — explainable, at least partially, by Dublin’s status as the Silicon Valley of Western Europe — while also ceding to a more opaque drift online. Now, all art is ‘post-internet’ as the artist media theorist Maria Olson put it; all contemporary art in some way shaped as an afterimage of global, networked thought. Against this shift, it is then hardly surprising that making sense of technology has become a noticeable feature of recent art. Tracking and making visible the diffuse flows of networked techno-capitalism — what theorists Jeff Kindle and Alberto Toscano have described as an ‘asethetic problem’ in their book, Cartographies of the Absolute 2015 — is a preoccupation shared by artists including Forensic Architecture, John Gerrard, Trevor Paglen and Yuri Pattison – whose work was recently acquired by the IMMA Collection. Another example here is the artist, Evan Roth, whose Artangel-commissioned project, Red Lines works to re-materialise the internet, showing us and indeed inviting us to live with the actual preconditions of its use.

Just before the web was invented, and years before it became the mainstay of everyday life that it is today, theorist Fredric Jameson claimed that the complexity of post-modern life created a challenge for human thought. The task of gaining traction and situating oneself with the broader capitalist system — a process he named ‘cognitive mapping’ had become arduous to the point of impossible. As with the work of the aforementioned artists – it is likewise impossible to cognitively map the networked system in which smartphones participate: impossible, at least for most of us, to visualise the sequence of actions and conditions that allow them to do so much. For the smartphone to function, we need to factor in — among innumerable other things — undersea cables, industrial labour, data packets and mining, along with storage and cooling facilities the size of small towns. Probably, if were able to grasp the totality of this scenario, we would not permit it the uncontested power that it now holds.

In his recent, fairly terrifying book, New Dark Age: Technology and the End of the Future (2018), the artist and writer James Bridle examines some of the many issues stemming from a limited view of networked technology. Particularly unnerving is the idea of automation bias, which describes the human tendency to prioritise technological knowledge over human observation. One example Bridle refers to, is tourists’ tendency to follow Google navigation — even when that involves contradicting their own real-world observations. Though we cannot fully understand how it works, such a bias means we lay more and more faith in technology. This blind assumption of infallibility has been known to lead some people to follow technological navigation even as they drive into lakes.

Watch James Bridle, Dark Age, New Dark Age Colonial Cables, Verso Books, Web Source.

Using smartphones involves an implicit acceptance of their suitability as a means of navigating the world; as a means of taking, looking at and sharing images; as a means of creating, displaying and exhibiting art; as a mode of consumption, and as a device that monitors and regulates the speed of life. It means to accept the exploitative and ecologically-ruinous conditions of their production and — whether we do so consciously or not — to accede to more and more of the same. This breeds even more complexity, rather than less. To wrest some control over the situation, we all have to be able to answer the questions Tillmans asks himself, and then to act. But, as Bridle makes clear: “Any strategy other than mindful, thoughtful cooperation is a form of disengagement: a retreat that cannot hold.” Luddite refusal will not suffice; instead, technology needs to be told that human hands can only move so fast.

Dr Rebecca O’ Dwyer is an art critic. Her writing has been published in Paper Visual Art Journal, Source Photographic Review, Art Review, Real Life, Enclave Review, Fallow Media, Spike, 032c, The White Review, Apollo, The Stinging Fly, The Tangerine, and elsewhere. From 2016-2018, she edited the online art writing publication, Response to a Request. She holds a PhD from the department of Visual Culture at the National College of Art & Design in Dublin, where she wrote about art criticism and capitalist realism.

This essay was commissioned by IMMA for The Edit #002, post digital e/Affect edited by Sophie Byrne. Read Editors Welcome – here. Also see the other articles featured by Jessica Foley and Charles Melvin Ess.

Further reading suggested by the Editor to accompany this piece:

To read more about Maria Olson’s coined term ‘post internet’ in her article, Post Internet, Art after the internet.

Download a text explaining Fredric Jameson’s ideas on Cognitive Mapping.

Categories

Further Reading

Existentialism in the (Post-) Digital Era by Charles Melvin Ess

Media theorist and philosopher Charles Melvin Ess of Oslo University, inserts the debate of ethics into the traditions of existential thinking for the IMMA Edit #002.

post digital e/AFFECT – Editors Welcome by Sophie Byrne

EDIT #002 by Sophie Byrne invites contributors to unravel some of the most pertinent issues to arise out the paradigm of the network. Recognised challenges and possibilities are set against the backdrop of D...

Obedient City, Smart City by Jessica Foley

Writer and researcher Jessica Foley, who works between worlds of art, network engineering and urban geography, plays with modes of art blogging and creative criticism in this piece for the IMMA Edit #002, us...

Up Next

Existentialism in the (Post-) Digital Era by Charles Melvin Ess

Fri Mar 1st, 2019