Obedient City, Smart City by Jessica Foley

Reflections on an EPIC conversation with artist Michelle Doyle

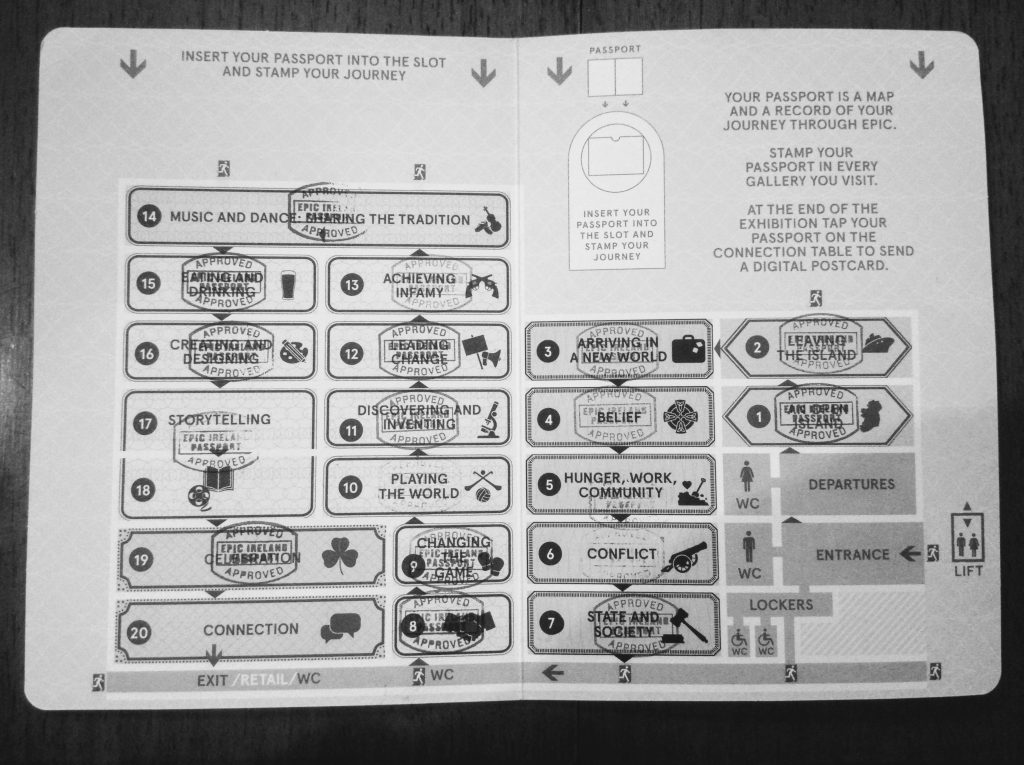

She took me to EPIC, The Irish Emigration Museum in Georges Dock, on the North Side of Dublin City. We said we were researching to start a language school called Language Connect and we got a courtesy pass, down into the brick arched basement of the 19th century Custom House Quay building. At the entrance we were given passports. We stamped them in each themed room we passed through. The museum was filled with audio and screens and projections. We counted 88 screens and 44 projections. It felt like we were inside the internet inside a city pretending to be a computer.

Afterwards, we had lunch upstairs amongst the galleries of shops and restaurants. We ate vegetarian burritos and buddha bowls. I drank San Pellegrino and she called me a “Lad”. I asked her to tell me about the Obedient City. The Obedient City, she said, is a Visitor Centre, where neighbours tell on each other and new museums spring up to sell experiences and data. It’s motto is splashed across the skin of the city, like pebble-dash. She pronounced the Latin with mock seriousness, as if introducing a royal, or a pope: ‘Obedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas,’ telling me it translates as: ‘The obedience of the citizens produces a happy city‘. I thought of our recent obedience in EPIC museum; stamping our passports, working to take in all the information, though it was at times overwhelming, intriguing and tiring. It’s like walking through a computer, she said, going through these “Museums of the Future” . (The words of poet Paula Meehan came to mind then, who says that a Museum is place where you put things to please the Muses. Amongst all the screens and passport terminals, I wondered what Muse we were appealing to.) Then she spoke about the idea of obedience, espoused by the architectural theorist John Ruskin in his book ‘The Seven Lamps of Architecture‘. He considered obedience to be “the crowning grace of all the rest”; the one “to which Polity owes its stability, life its happiness, faith its acceptance, creation its continuance.” According to Ruskin, this principle was the foundation of the City itself. As a delicate balance of freedom and restraint, obedience was a recipe for civic wellbeing: Freedom + Restraint = Happiness. As I chewed my lunch, I ruminated on how this equation plays out in the city, wondering how architecture could claim to do so much with apparently so little…

Over lunch, I learned that the politics of obedience has been emblazoned on the skin of Dublin city for four hundred years, on its Coat-of-Arms. She told me, “There’s really well painted ones outside St. Patricks Cathedral. And then there’s ones that are acid-rainy-melted everywhere else… It has the crown on it as well. Which is so insane. It’s definitely pre-state, and it has a sword as well. It was so strange and colonial. Just the fact that it was obviously a motto that was chosen by the English for Dublin.” She began to really notice these Coat-of-Arms while she was on a residency with A4 Sounds, a participative socially engaged arts and education centre in the North Inner City. This was late summer, autumn time and there were growing movements advocating the right to housing, with activists calling people to ‘take back the city’ by occupying vacant properties on Summerhill and Frederick street: “All the stuff to do with Frederick street was happening all around, all the occupations, it just felt like everyone was being very disobedient. And everyone was really happy. So it’s clearly not true,” she said. It’s clearly not true that the Obedient City is a happy city.

“A museum is just as algorithmic,” she said, “as Netflix. And the way that you make a museum is based on the information people want to hear. They’re like User Persona’s. I wouldn’t be surprised if that [the EPIC Museum] was designed in the same way that you would design an app. You would sit down and you would say, ‘John. Age: 49. Canadian. His likes and dislikes. Things he finds easy or difficult. And then, his User Journey and his Character Traits.’” As she spoke, I marvelled at the idea that the city was becoming just as algorithmic as Netflix. I began to see Dublin enmeshed in a global historical trend to produce well connected, agile and obedient citizens with the appetites of tourists. As I listened to her speak, images of pebble-dashed visitor centres and museums of the future merged with online entertainment distributors into a composite model of the ‘Smart City,’ and Dublin was marked to be the most obedient, most smart of them all. Now the city is full of networked openings; digital pores and eyes and ears sensing and computing all the goings on of every moving body. The obedient city is glitching between the wildest dreams of imperialism, capitalism and democracy, crystallizing a new datafied kind of tourist trade. Calling me back from my daydream she asked me; “So how would they have gotten that information in the first place? How would they have known? Would they have had to buy that off someone else to figure out where all the tourists are coming from?” I don’t know, I thought, the internet is just everywhere now isn’t it? Not long after this awakening, she told me that she was learning to code in JAVA so that she could build her own dashboard, equipping herself with the tools and literacy to navigate the ‘Obedient City‘ in her own way. Then she left me with my recording devices, heading off to buy a gel-pack to soothe her eyes, sore from the screen-time teaching english to children in faraway cities.

Michelle Doyle’s generous and performative narration of the themes and materials at play in her ongoing work as an artist and teacher of EFL, during our EPIC adventure, tells of the complex ways that artists are negotiating a ‘post-internet’ world and a globalized Ireland. In her recent exhibition Obedient City, Doyle makes a trope of the Visitor Centre and in so doing casts a strange light on Dublin City. Her off-register mimetic approach calls into question larger realities of civic life, but with a buoyancy that does not leave one feeling depleted or despondent. Instead, her work piques critical attention towards the unfolding realities of city life in Dublin by estranging the powerful, implicit metaphor of obedience inscribed in it’s motto. To my mind, Doyle sets up a tension between the old logic of Dublin’s gatekeepers and the contemporary ambitions of Dublin City Council to establish the ‘Smartness’ of the City. Reflecting on Michelle Doyle’s Obedient City as a foil to the Smart City, I wonder if the living, breathing City’s unsung motto might better be written as: Inobedientia Civium Urbis Felicitas.

About the Author/Artist

Jessica Foley writes prose and poetry, and works as a trandsdisciplinary researcher and teacher. Her artistic practice involves transdisciplinary collaborations exploring fiction, technology and the human condition through writing and multi-media. She is currently an Irish Research Council Postdoctoral Fellow at the Social Sciences Institute, Maynooth University, (2018-20) where she is exploring the function of fiction in parsing the worlds of ‘smart’ technologies. She is a co-founding member of the Orthogonal Methods Group and writer-at-large with CONNECT, Trinity College Dublin.

Michelle Doyle lives and works in Dublin. She attended the National College of Art and Design where she received a Bachelor of Fine Art Media in 2013 and completed her Masters in Art and Research Collaboration in Dún Laoghaire Institute of Art, Design and Technology, Dublin in 2016. She was recently awarded the A4 Sounds Artist in Residence Award (2018) and the Sirius Residency Award (2019). Recent group exhibitions include Athrá Titim Gach Rud, Repeater, Galway (2018); Yoga ForThe Eyes I, Open Ear (2018) and Yoga For The Eyes II, Dublin (2018). Michelle’s solo exhibition, entitled Obedient City (2018) was shown in A4 Sounds and relaunched for Culture Night. She also plays in punk band Sissy and solo as Rising Damp.

This text was commissioned by IMMA for The Edit #002, post digital e/Affect Edited by Sophie Byrne. Read Editors Welcome – here. Also see the other articles featured by Rebecca O’ Dwyer and Charles Melvin Ess.

Further reading suggested by the Editor to accompany this piece:

To read more about Irish artists working in Dublin city, see Johanna Walsh’s article digital desire lines.

Categories

Further Reading

post digital e/AFFECT – Editors Welcome by Sophie Byrne

EDIT #002 by Sophie Byrne invites contributors to unravel some of the most pertinent issues to arise out the paradigm of the network. Recognised challenges and possibilities are set against the backdrop of D...

Existentialism in the (Post-) Digital Era by Charles Melvin Ess

Media theorist and philosopher Charles Melvin Ess of Oslo University, inserts the debate of ethics into the traditions of existential thinking for the IMMA Edit #002.

Thinking of the Network by Rebecca O’ Dwyer

For the IMMA Edit #002, Berlin based art critic Dr. Rebecca O' Dwyer points to how the ‘physicality’ of the network, or lack thereof, preoccupies the work of game changing artists.

Up Next

Introducing the new IMMA Magazine

Mon Nov 26th, 2018