The Last Ferry, for Ruth Libbey O’Halloran

This essay, The Last Ferry, was conceived for The Maternal Gaze series and hinges on the ways Beth O’Halloran’s mother’s ethics and love of nature shaped her practice. The personal essay and accompanying images focus on a road trip O’Halloran shared with her mother, Ruth Libbey O’Halloran. They travelled from Ruth’s native Maine to the island of Nova Scotia. It is a meditation on maternal love, loss and the transference of enduring codes for living.

……………………………………………………………………………

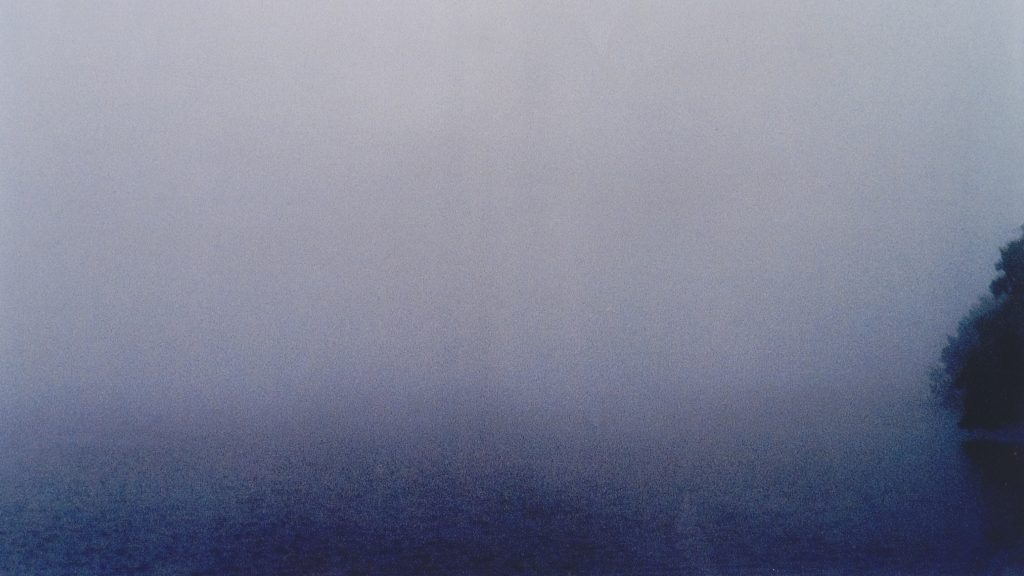

I’m awake before you. Is that a first? I creep out of the motel room as quietly as I can, to feel the air and look through a lens – to gain a little distance. The lake is hidden in a thick, blue-purple fog. I can’t tell where the air stops and the water begins.

It is cool and damp – Canadian cold meeting the last warmth of a New England summer. I am standing on a small wooden dock, wrapped in mist, wishing I had brought the cardigan you gave me. There is a tree to my right – the only solid thing – but even that is slipping from view. The camera makes a click so loud, ducks swim away.

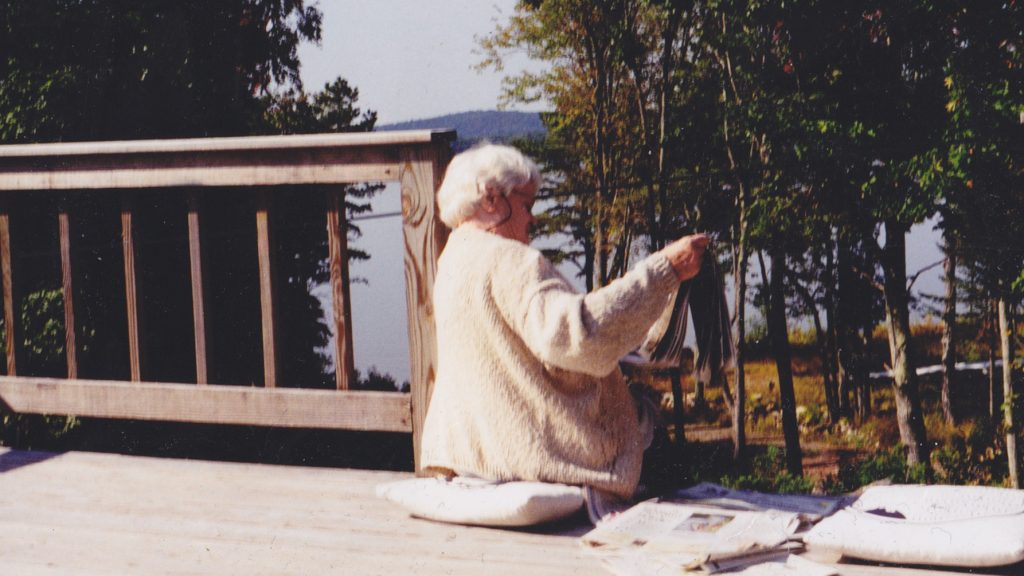

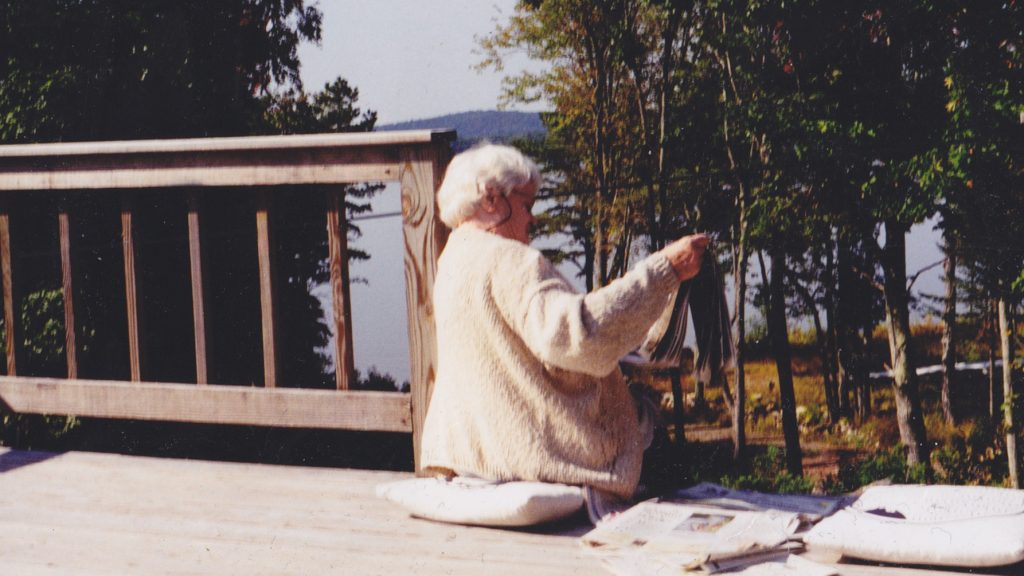

These trees, the birdsong I can match to its sources, the sound of lake water lapping the shore. All these things you led your six children to from the start. You were a girl-scout and can mimic a chickadee’s call so well, he answers you. ‘You never need to get lost in the forest,’ you said. ‘Just look for the lichen on the north side of the tree trunks.’ You catch my arm before I step on a lady’s slipper, then explain why the flower is so rare. You bend to show me the lily of the valley hidden in shadows and your kitchen sink is always, always full of potting soil and clippings. There is an open book on your lap, even as you drive. These things I thought every child knew, until I wasn’t a child anymore.

I know you are tired. We both know that today’s trip is the last you will take and that the sickness in you is what is keeping you dreaming, as milky light bleeds through the screened windows.

I can see your lamp flick on inside as a lone streetlamp glows orange above a blue-grey garden.

By the time I get back in, you are busy packing. The kettle hisses and clicks as you make coffee and open a little milk jigger with a squirt. You hand the coffee to me with a bundle wrapped in a napkin. ‘Found you a muffin.’

Back in the car, we drive towards the ferry port. Today we leave Acadia at Maine’s northern tip to travel to Nova Scotia, so you can visit the first place you and your husband went to be alone together – after having three children in as many years. You are quiet on the drive, except for the high-pitched sound you make when the car dips into pothole after pothole. Your hand clutches your abdomen.

After the diagnosis, you said, ‘No more chemo. No more surgeries. I’m tired of being a pin-cushion.’ Instead, you wanted this trip. I dreaded the idea of being in a car and then the cabin of a boat with you – seeing your pain close up. At every chance, I slip away. On the deck, I take shots of the rising sun – the whole sky pinks and greens above the wide sea. Back in the cabin, you ask to take some. Holding the camera with unsteady hands, you point it through the porthole. ‘That sky sure is showing off,’ you say.

I am not taking any photos of you. It doesn’t feel right, knowing that soon you won’t be able to see the printed images. Instead, I photograph the things you always pointed my chin towards – the skies, the trees.

We go for a meal where you and Dad had gone with a seat right on the bay. You eat a lobster dinner, your chin covered in butter, you lick each finger, grinning.

A few days after we get back to Portland, you get a call from your good friend, the Monsignor. He had been up to Lewiston overseeing a funeral and had wandered around Mount Hope Cemetery. He stopped in his tracks when he came across a headstone with your name engraved on it, already placed on a plot. There was your birthday followed by a dash and a blank space. ‘Eager beavers, aren’t they,’ you said with a chuckle.

And of course, you had to see it. Which is how I am once again the designated driver for this macabre road trip.

We avoid the turnpike and take the scenic route 202 which leads us down Main Street. Passing a cluster of discount stores, you say, ‘Let’s just pop our heads in to Marden’s in case there are any bargains.’ Then back down Main, past the red brick colonial in which you were born and raised. ‘There’s 612. I can’t for the life of me fathom why they pulled up all the lilacs. The place looks as bare as a penitentiary.’

We drive to the bridge, passing the W.S.Libbey Mill where your father made his name. We both look at the red brick mill, hanging over foamy waters. There used to be a rock on each side of the falls – one looked like an Indian profile and the other was the image of George Washington.

I ask you, ‘What tribe was it that lived in this neck of the woods again?’

‘Heavens child, how do you not know that? And you, the daughter of an historian. The Abenaki. But they didn’t last long. Got wiped out by smallpox, courtesy of the colonists. Never stood a chance.’ You look to the other side of the bridge at a huge purple building, ‘My word, look at the godawful colour they’ve gone and painted the bank this time.’

The two rock faces are long gone – worn away by the rapids and the blasting for industry. We drive on and through the gates with Mount Hope Cemetery engraved on slabs of granite either side. When we get to the familiar curve, you break the silence with, ‘You wait in the car, honey. You might get upset.’ I nod and swallow. I watch you walk in your sensible shoes through thin snow. When you get to your plot, you use your foot to clear snow and leaves from your young husband and your eldest daughter’s headstones, before doing the same to your own. Then you turn with a satisfied nod and sit back down beside me. You’re smiling when you say, ‘Let’s go to Sam’s. You look like you could do with a sandwich.’

View this essay here as part of The Maternal Gaze Series.

Categories

Further Reading

The Artist’s Mother: Lucie and Daryll

IMMA's Head of Collections, Christina Kennedy, introduces us to The Artist's Mother, a project created in responses to the Freud Project. Inspired by Lucian Freud’s paintings of his mother, Lucie, the projec...

Photographs Reassembled

Sarah Allen, curator at Tate Modern interviews Jan McCullough, IMMA Residency artist, about the role of photography in her work, what informs her methodology with the artform, how her practice has evolved wi...

The Green Journal: Spring

In this second Green Journal entry, Sandra Murphy from our Visitor and Engagement team , will keep you updated on some of the seasonal changes on the grounds at IMMA. Topics include some tips on how to creat...

Up Next

The Green Journal: Spring

Sun Apr 11th, 2021