Marguerite O'Molloy: Installing One Foot in the Real World

I am really honoured to have the enviable job of curating the forthcoming exhibition from the IMMA collection. Someone once asked me if curating from the collection was like being a kid in a sweetshop; in some ways it is. You are spoilt for choice with over three and a half thousand works to select from; but that number does not reflect the variety and complexity of the works. So where to start?

The idea for the exhibition One Foot in the Real World developed over some time, I was looking at themes thrown up by the temporary exhibitions that we are going to be showing come our major relaunch in October. What piqued my interest was Eileen Gray’s fascination with transformation; Leonora Carrington’s depictions of surreal domestic interiors and Klara Liden’s subversion of public space.

I started to plan an exhibition which was an exploration of scale and the body and the psychology of space and included lots of basic everyday objects – like tables, doors, windows, keyholes, bricks and mortar!

I was particularly excited that we were building a large brick structure to house Mark Manders Reduced Summer Garden Night Scene, 2002. Manders had made a number of versions of this night-time landscape, and this version was shown twice previously at IMMA – first in Mark’s solo show Parallel Occurrence accompanied by a gorgeous full colour catalogue and again in I’m always touched by your Presence Dear.

I had never directly worked on installing this work, so during my research I needed to do a bit of digging to find out how the piece was constructed. The practicalities of making installations or demanding sculpture had always been a hook for me as a curator; I love seeing first-hand the lengths artists go to in order to create unique experiences.

My interest was piqued by this installation shot at Documenta in Kassel in 2002 where the piece was first installed.

Sand, porcelain, wood, iron, cat-skin, rope, glass, 202 x 470 x 200 cm. Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, Purchase, 2005. Courtesy: Zeno X Gallery Antwerp, photographer: Geert Goiris

I noticed the walls housing the piece were originally brick. It could also be installed with plain plastered walls, which was how IMMA had done it to date, but for me in the context of this particular group exhibition the brick was important – it changed the palette of the work, and added lines of perspective. It also created a very different psychological impact in the space.

Brick was definitely a more complex option and involved a lot more work and planning – building a brick wall was not a difficult thing in itself, but building a brick wall using wet mortar in a museum environment was!

We were very fortunate to have generous support in the supply of materials and labour from Quinn-lite who manufactured the aircrete blocks that the artist specified for the piece. A team of bricklayers built the wall working to a very exact measurement of 2010mm wide for the glass wall at either end of the enclosed landscape.

They were allowed a variance of 3mm each side.

A credit to them, it’s a very tight fit!

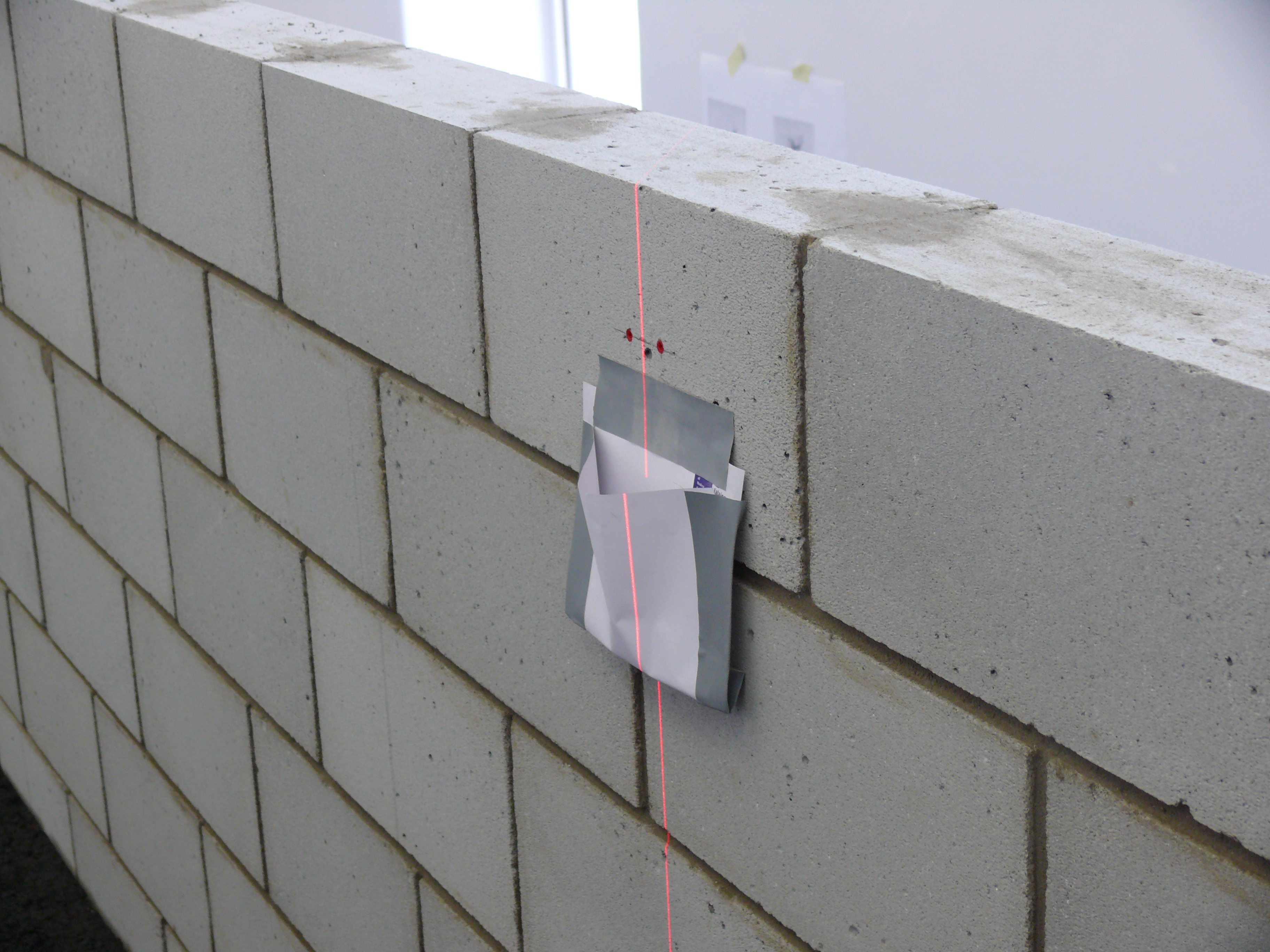

Art-handling know how, a pocket is hung just below the drill point to catch any falling dust. Crew use laser to get the measurement bang-on.

Our colleagues at National Gallery Ireland kindly lent suction grips for lifting the glass into place.

Basic doorstops hold the glass in its final position

The work was carefully planned to take place before any other artworks were installed in the area, as the risk from dust and moisture was significant. The newly laid floor and freshly painted walls were wrapped to avoid any marks from cement. Dehumidifiers were on max to help reduce the moisture content in the air too.

The landscape part of the sculpture was made from 4 distinct pieces which slot together; these are crated for transport and storage, and the glass sheets that frame the piece were separately crated. The installation needed to be choreographed quite precisely and its construction was theatrical at times; at one stage two of our art handlers had to limbo-dance beneath the sculpture.

During the first installation of this piece at IMMA, Manders took off his shoes and walked across the landscape to carefully position one of the freestanding objects. And now that the piece was in a national collection, we were treading more carefully having to work out a way to position objects without placing pressure on the surface of the work; but our team of art handlers loved a good challenge.

A conservation grade low suction vacuum is used to dust the surface

All of these small details disappeared in the final installation. Installing sculptures of this scale was a kind of theatre and involved a moment of alchemy that never fails to amaze.

I was thinking of installing a tiny steel keyhole by Iran do Espirito Santo on a wall next to this work, but the final positioning of works can change at the last minute if something is not working in the space.

8 x 3.6 x 1.8 cm, Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, Donation, Artist, 2010

At 8cm high Iran’s piece sits in the hand and can be easily moved about and held in place to try out different positions. So do make sure to check back in in October when we reopen, and see whether one of the largest works in the collection ends up next to one of the smallest.

-MO

@marguerite_o_my

One Foot in the Real World curated by Marguerite O’Molloy, Assistant Curator of Collections.

Opening 12 October 2013