Homecoming: Frank Bowling and Lucian Freud

Now showing at IMMA are two of the greatest painters of the 20th century, Frank Bowling and Lucian Freud. We invited Dr Nathan O’Donnell, currently IRC Enterprise Postdoctoral Research Fellow in connection with the IMMA Collection: Freud Project, to write on the relationship between Lucian Freud and Frank Bowling.

When Frank Bowling started out on his career as an artist in London – a recent graduate of the Royal College of Art, originally from British Guiana – he was given early encouragement by the already well-established older painter Lucian Freud. Bowling’s graduating year included David Hockney and R.B. Kitaj, who coined the term ‘the School of London’ to describe the cross-generational milieu of painters and sculptors operating in the city at this time, a network of mostly-figurative artists who, according to Kitaj (and many commentators since), shared much in common. Freud and Bowling would have interacted socially as well as professionally, not least at certain pubs and nightclubs they both frequented, including – for many years a principal haunt of Bowling’s – the King’s Arms on Fulham Road, not far from the RCA, known to all colloquially as ‘Finch’s’.

Bowling’s early work, like Freud’s, was figurative. ‘He’d go out of his way to encourage me’, Bowling said of Freud in a 2012 interview. ‘He’d often drop by – but that didn’t last much past the time I stopped doing figurative painting.’ Encouragement also came from Graham Sutherland and later from Francis Bacon, whose influence can be clearly detected in some of Bowling’s early work, though he had already begun to question aspects of Bacon’s work before leaving London, in 1967, for New York.

Freud may also have been interested in Bowling’s background, an emigrant like himself, from Bartica in British Guiana. Freud had an at least passing connection with the West Indies. He took a long soujourn with the socialite Ann Fleming at her home, Goldeneye, in Jamaica, where her husband Ian wrote the first James Bond novel; Freud also went on to produce a startling frontispiece for The Baths of Absolom (1954), an account by a British travel writer, James Pope-Hennessy, of his journey through the colonial infrastructure of the Windward Islands in the West Indies, taking in Dominica, Saint Lucia, and Martinique.

For both Bowling and Freud, London was a formative early influence. Freud thought of his arrival in the city, at the age of eleven, as a sort of homecoming. He considered England a place of gracious respite, a welcoming haven after his family’s anxious flight from Nazi Berlin. He seems to have felt a lifelong gratitude to the country. He received British citizenship in 1939, but in private he went further, describing himself, not just as British, but as English.

Bowling arrived in London, two decades later, as part of the ‘Windrush Generation’. He was 19 when he arrived, in 1953, to stay with his maternal uncle in West Hampstead. He has described the mesmerising first experience of the Tube from Waterloo Station, the crowds of passengers raucous and euphoric, gripped by ‘coronation fever’. Like Freud, he says that ‘the moment I arrived in London, I knew I was home’.

Though they date mostly from the period after he left London for New York, the traces of his native Guiana in Bowling’s work – in particular the image of his mother’s shop, which becomes almost an ideogram, screen-printed like a large stamp in the background of his work from the 1960s on – would surely have had a particular resonance for Freud, whose relationship with his place of birth was likewise complex and ambivalent. In the early years of his career, Freud was repeatedly referred to by critics and commentators in terms of his ‘Germanness’, an appellation that must have stung, given his commitment to England, his sense of his own Englishness, not to mention his sustained hatred for the Germany of the Third Reich. Nevertheless in his work of the late 1940s he found himself reckoning with the influence of the great German painter, Albrecht Durer, prints of whose work adorned his family’s mantelpiece near the Tiergarten in Berlin when he was growing up. He may have renounced the place of his birth, but this does not entail a straightforward disavowal of his past.

For his part, while his work was often openly and powerfully political, addressing the post-colonial legacies of black experience, Bowling has voiced ambivalence about the ways in which his work and that of his contemporaries has been classified as ‘Black Art’; in 1971 he wrote an important essay, responding to an exhibition of black artists, in which he made clear his reservations about how the specifics of an art work can be flattened or subsumed by the categorisation. Both Freud and Bowling’s work is thus, in different ways, troubled by the politics of identity, and how it plays out within the operations of the canon; both artists were informed by a complicated sense of cultural inheritance, racialised politics, and contested geographies.

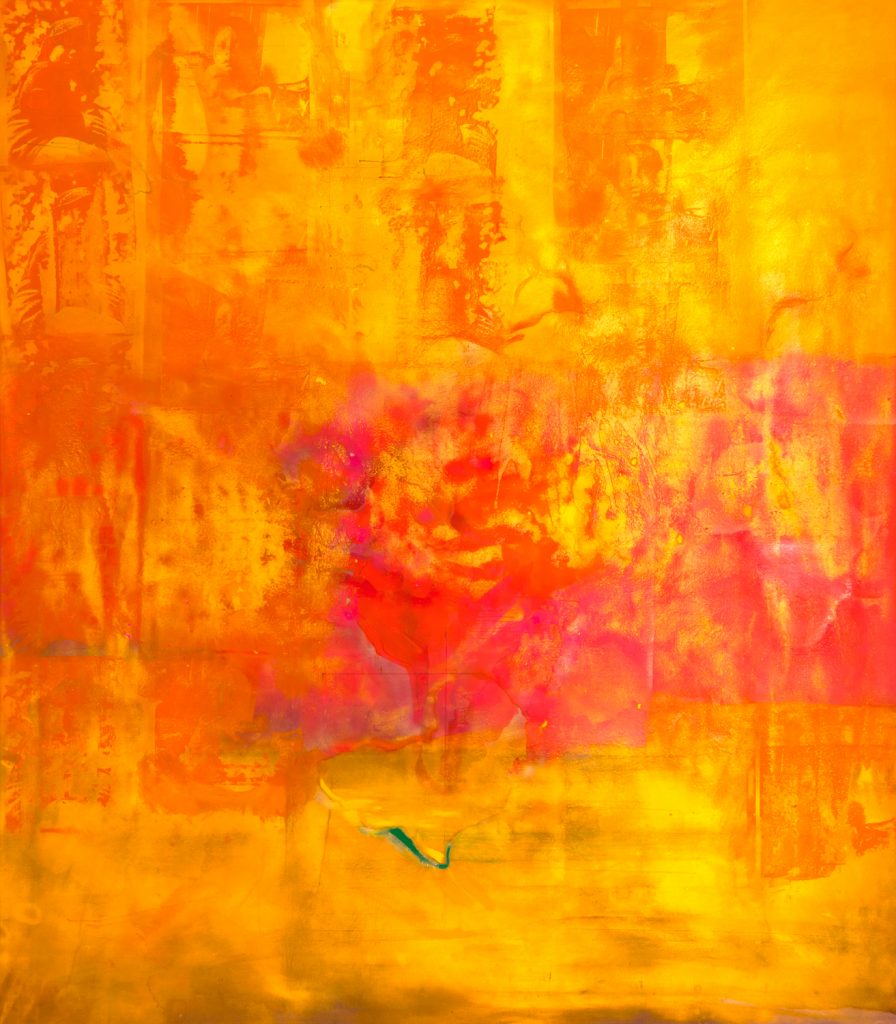

After a brief number of years in the same milieu, Freud and Bowling’s work took different paths, Bowling moving into large scale abstraction (influenced by action painting, colour painting and collage), while Freud remained committed to representation throughout his career. Both artists, however, went on to spend many years painting, in relative obscurity, with single-minded dedication to their work, exploring – in different ways – the complicated interplays of nationhood, time, home, and memory.

Frank Bowling ‘s exhibition Mappa Mundi is on view until 8 July.

Lucian Freud’s work can be seen alongside the work of contemporary artists in the exhibition The Ethics of Scrutiny, curated by Daphne Wright until 2 September.

There is currently a special offer to see both shows for just €10 on the same day. Click here to book now. (discount will automatically be applied in your shopping cart)

Categories

Further Reading

Behind the Blink. Freud Project Advertising Campaign

To celebrate the exhibition IMMA Collection: Freud Project, we asked advertising agency Irish International BBDO to create a 20 second advertisement that would capture the feeling of seeing a Freud work in t...

Landmark Lucian Freud Project and 2016 programme

IMMA announces landmark Lucian Freud Project for Ireland alongside an expanded 2016 programme of new work celebrating the radical thinkers and activists whose vision for courageous social change in Ireland a...

Up Next

IMMA celebrates the ten-year anniversary of The Burial of Patrick Ireland

Mon Jun 18th, 2018