Helen Cammock: The Long Note at IMMA by Eva Kenny

In association with IMMA’s 2019 programme – featuring exhibitions by Wolfgang Tillmans, Les Levine, Helen Cammock and Doris Salcedo – Dublin based writer and researcher Eva Kenny explores overlapping themes of borders; Northern Ireland, Brexit and the Civil Rights Movement, that comes to the fore in Helen Cammock’s current exhibition The Long Note presented in the Projects Spaces. Cammock’s seminal film strikes a chord with Kenny’s wider interests in the cultural specificity of language and the importance of capturing the female voice within Ireland’s history; offering an emotive testimony to ‘remembering’ historical events in more precarious times.

In recent months, Irish art venues have hosted an unprecedented number of exhibitions on the themes of borders, Brexit and Northern Ireland. These cross-border initiatives are generating welcome attention for the North, indicating that at the level of culture, there is a public desire to understand the impact of the vote for Brexit and to revisit the early years of the civil rights movement in the North, before the Troubles began, to avert a return to those terrible days. Among the exhibitions that explore these themes was Wolfgang Tillmans’ Rebuilding the Future, earlier this year at IMMA, which characterised the postwar European period of globalisation and free travel as a romantic, expansive period now threatened by Brexit and the increase in right-wing politics in Europe.

At IMMA this month, two exhibitions mount two distinct international responses to the Troubles; American artist Les Levine’s photographs of the Troubles: An Artist’s Document of Ulster from the early 1970s, and British artist Helen Cammock’s The Long Note.

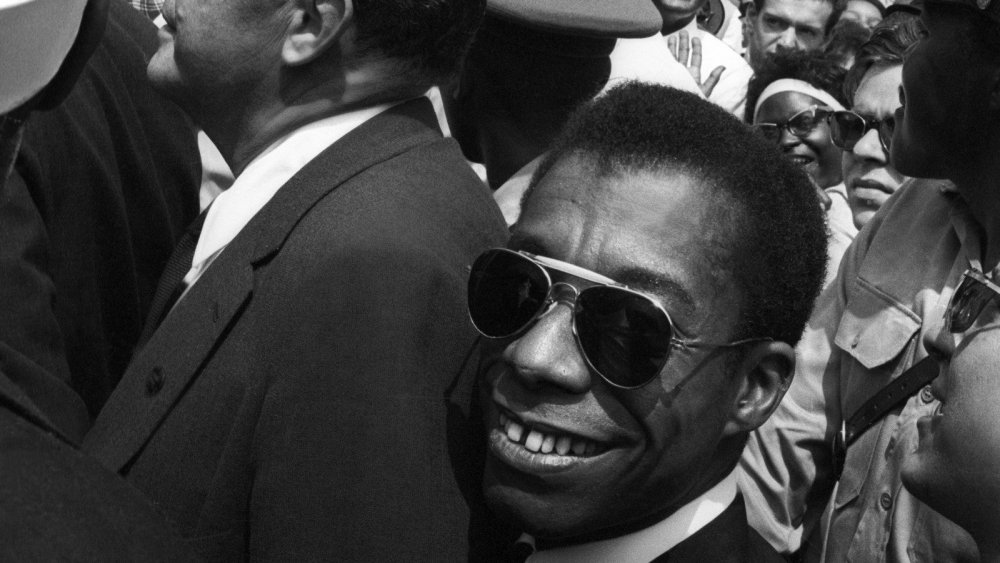

In The Long Note, a film commissioned by the Derry art space Void in 2018, the artist demonstrates a more sustained interest in Northern Ireland than most members of the House of Commons have done in the years since the Brexit vote. In the film, the artist listens carefully to the local women that she interviews, weaving their voices together with clips from archival footage of the 1968 march in Derry and the Bloody Sunday march in 1972, interspersed and overlaid with her own voice reading their stories, as well as extended pieces of text and song by Nina Simone and James Baldwin. In the words of these luminaries of the American civil rights movement, are refracted the politics from which the protesters in Northern Ireland drew inspiration, in looking West to the United States rather than East to the students’ movements in France or the Czech Republic for instruction.

Language in Northern Ireland is a combination of extremely indirect speech and extremely direct speech; full of allusions, shibboleths, winks and details that the outsider may not appreciate, on the one hand, and outright demands to spell a name, say “H” or sing “The Sash” on the other. In this regard, it presents both a rich opportunity and a particular challenge for an artist whose material is the voice. Perhaps it is for this reason the film ended up an hour and twenty minutes longer than originally intended. The film gives the floor to both types of speech, as the artist reconstructs a largely unfamiliar account of the role of women in the early days of the civil rights movement and the Troubles that followed.

Speech rarely comes more directly than in the form of Bernadette Devlin, the Derry activist and, at the time, youngest ever Member of Parliament in Westminster, who went to prison for agitation against police violence in Northern Ireland and the military occupation that followed. In the film Devlin describes her own status as the poster girl for the civil rights movement to the exclusion of other women’s voices, as “the exception that becomes the rule”. She is not named in the film for this reason, and nor are any of the other women, as Cammock introduces each voice as both exceptional and unexceptional.

The domestic detail in the stories is often heartbreaking, like that of the woman who made her son wear clean underpants to the Bloody Sunday march in 1972 so that if he was killed — which he was — the soldiers would know that someone cared about him. The observations are also wry and hilarious, as when Nell McCafferty describes women joining the armed protests in Derry:

“My mother and the other women in the street, all of whom had worked in the shirt factories and had experience with assembly line management took over the petrol bomb station down there… and because they were all used to cooking, the exact amount of ingredients were put in—the petrol, the sugar, the flour, and they made very good wicks. And when I watched those women making the petrol bombs, I knew that the revolution had come.”

These scenes go straight to the heart of the sexual politics of the civil rights movement. If the first mother had not let her son participate in the protest, she would have made “a mammy’s boy out of him”. If the second group of women excelled at factory-line bomb production it was because they had retained their jobs, while Derry men had largely been put out of work as a way to undermine their ability to provide. The film reminds us that as much as the civil rights movement was a function of the depressed economic situation across the North as manufacturing contracted, and housing and voting rights were withheld from Catholics, there are complicated questions to be asked about gender equality within the movement. It builds a picture of domestic violence that, as part of the gentrification of the political struggles of the 1960s, has been smoothed out of history.

Why, Devlin asks, would Northern Irish women take from their husbands what they wouldn’t take from British army soldiers? Why were the women who stepped forward to lead the movement, when internship began in 1971, returned to the kitchen when the men got out of prison? Why would one accept that the various forms of inequality suffered in the North would be ordered according to importance, with women’s social and reproductive rights deemed secondary at best?

The study of the contradictions and complications of power, particularly in relation to race, gender and class, was named “intersectionality” by the Black feminist scholar and civil rights advocate Kimberlé Crenshaw in 1989. In conservative art discourse, however, intersectionality is often treated like a trendy process of addition, disparaged as something that has to be put into artworks for the sake of political correctness. In fact, it is just the way things are. Removing these contradictions from history or art for the purposes of editing is a subtractive method that takes more effort than just allowing peoples’ voices to be heard. Cammock, in The Long Note, elicits and shapes the testimonies most abundantly suggestive of these competing claims for political attention and representation.

In Devlin’s interview, for example, the impoverishing effects of a politics devoid of these contradictions are clear when she describes her introduction to feminism in the US in 1969, having “skipped the two pages” on the subject in working class Derry. Feminists, she thought, were white professional women who simply outsourced domestic labour to women of colour, until she started to work with Black feminist organisers in the American civil rights movement. Even now, she notes, post-Peace Process Northern Ireland is too exclusive of support for cross-cultural movements, too committed to nativist politics to care about civil rights for overlapping interest groups.

Part of the current rush to capture the 1960s before they disappear forever is a desire to understand how political formations, as well as memories, are produced or suppressed. The 2017 film I Am Not Your Negro recentred James Baldwin as a hero of the American civil rights movement, a position long denied to him because he was openly gay. What else has been excluded from our stories about the civil rights movement in Northern Ireland, and how do these exclusions contribute to today’s political deadlock? Underlying the current cluster of exhibitions around the border and civil rights is therefore the need to go back for these stories, as Devlin puts it, in order to understand how they intersect with the present.

About Author

Eva Kenny is a scholar and critic based in Dublin, Ireland. She has just finished her PhD in Comparative Literature at Princeton University, writing a doctoral dissertation on Samuel Beckett’s legacy amongst American Minimal and Conceptual artists of the 1960s and 1970s, and is at work on a book manuscript on Beckett’s art of dispossession. She has published widely on the art and literature of the postwar period in the US and Europe.

About the Exhibition

Continuing until Sunday 12 May 2019, the exhibition Helen Cammock, The Long Note at IMMA comprises of the film work The Long Note, Shouting in Whispers (2017) and research material. Co-curated by IMMA curators Janice Hough, Residency and Artists’ Programmes and Sophie Byrne, Talks and Public Programmes. Admission is free.

Forthcoming Roundtable Discussion: Sat 25 May 2019

Exploring change and challenges pertaining to the role of women, civil rights and politics today. Speakers include Susan Mckay, Kitty Holland, Pat Murphy and others.

Acknowledgements

Text Commissioned by IMMA 2019.

Editor: Sophie Byrne, IMMA Talks and Public Programmes.

Images: Courtesy of the artist Helen Cammock and photographer Ross Kavanagh.

Further Reading and Resources suggested by editor to accompany this piece

Further Reading and Resources suggested by editor to accompany this piece

Additional Resources

Additional Resources

Categories

Up Next

Fergus Martin, Then and Now

Tue Mar 19th, 2019