Fergus Martin, Then and Now

The purpose of IMMA’s newly initiated Then and Now series is to set significant early works by artists represented in the museum’s collection within the context of their current practice. Ideally, this may cast a retrospective light on the earlier work, while also highlighting an artist’s enduring concerns, as well as illuminating more recent innovations or modulations that have yet to run their course. In this spirit it seems useful to open this essay by revisiting an account I wrote more than twenty years ago of Fergus Martin’s Six Paintings for Le Confort Moderne, Poitiers, 1996, shortly after that series was completed. I do so in light of the fact that the first painting in the series was subsequently acquired by IMMA and may be seen as the cornerstone of the inventive configuration of old and new works presented on this occasion.

Back then it seemed evident that Martin’s painting in general – his prime pre-occupation at the time – was, in common with that of certain of his peers, beholden to two historically influential strains of non-objective art. The first of these was the tradition of the abstract sublime, with its roots in nineteenth-century European Romanticism and its implicit yearning for transcendence. The other, more splintered tradition was that composed of all those critical reactions to the abstract sublime that had sought in some way to clip its wings and bring it back down to earth. The individual painting that best exemplified the tension between these two contrasting inclinations in 1996, conjuring a kind of suspension between heaven and earth, was the painting in question, which also supplied the point of departure for the Confort Moderne suite as a whole, as indicated by the title it bore at the time: Untitled 1, 1996.

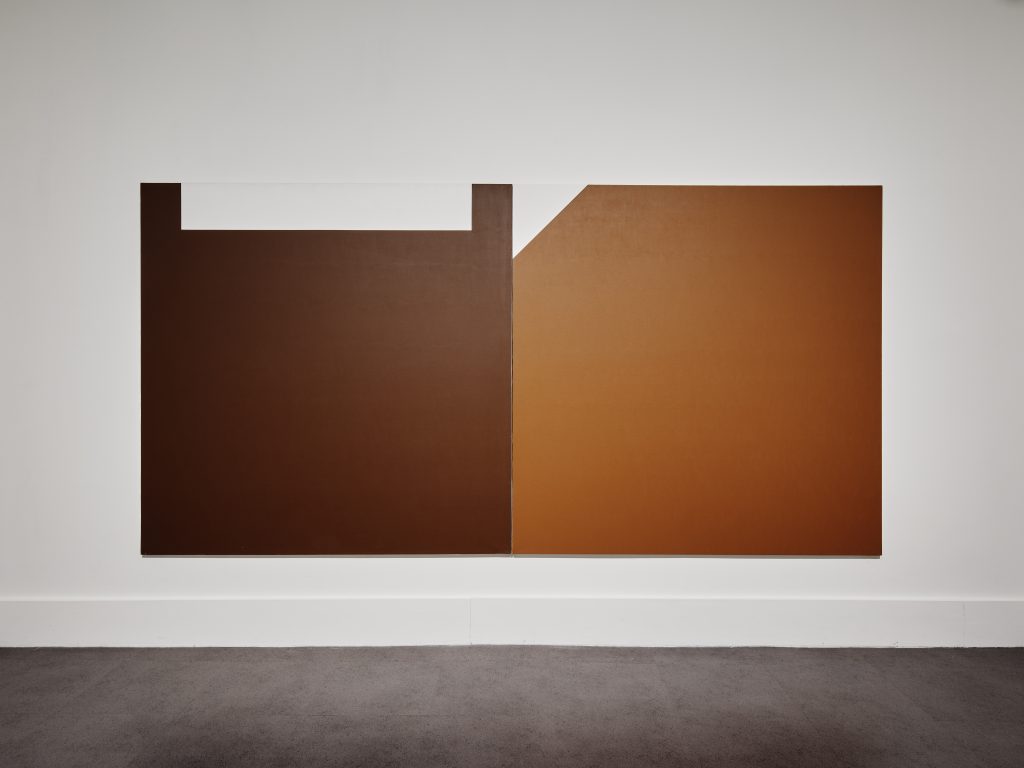

This is a large, square painting in acrylic on canvas whose entire surface is a more or less evenly painted raw sienna, apart from a small triangle in the top left-hand corner, which is painted white. Standing in front of the work back then, the heavy expanse of its brown field appeared to ground the flighty motif, preventing it from soaring into the heavens. At six-foot square the work was, I felt, ‘substantial, but not enormous’ and ‘powerful, but not over-powering’, largely due to the fact that it was ‘reassuringly human-sized.’ The other five paintings in the series, painted in subtly differing shades of brown, shared the same format but with one signal difference. All of these canvases were variously elongated on their horizontal axis to the right. So, while the largest of them was still six-foot tall and emblazoned with an identical white triangle in its upper-left-hand corner, it was exactly twice as wide. Its effect on the viewer was thus crucially different. In contrast to the initiatory painting, it seemed to me that the

[the] human proportions have been distorted. The ideal has given way to the unexpected; reason has been invaded by unreason. In fact, the word ‘unreasonable’ is one which crops up frequently in Martin’s diffident, down-to-earth account of his intentions as a painter. While he is refreshingly unembarrassed by the thought of producing a painting that is beautiful, he is equally unabashed by the notion of producing a painting that is awkward. Yet there is no sense that he is straining to produce either merely for effect.

This revisiting of a twenty-year-old commentary is motivated, not by self-indulgent nostalgia, but by the fact that this anchoring canvas from the Confort Moderne series has now come to anchor an ensemble of a very different kind. On this occasion it has been paired – in one of the exhibition’s four discreet spaces, including a stretch of corridor – with a matching Untitled painting, from 1998, of the same dimensions, but featuring a darker acrylic ground of burnt umber. In lieu of a white triangle in an upper corner, this later painting features a long, narrow, centred rectangle of white that runs along most of the canvas’s upper edge.

It is at once reassuring and disconcerting to realise that Martin’s tendency toward the productively ‘unreasonable’ remains undiminished in 2019. The latter reaction derives from our realization that both of these self-sufficient paintings, executed two years apart, are perfectly capable of holding their own, and might easily have commanded one wall each in the room they now share. Yet the artist has chosen to abut them unexpectedly, allowing the manifest tension between their distinct colouring and geometric composition, when viewed in close quarters, to testify to their disparate provenance and, by implication, the passing of time between their moment of origin. Sparks fly between these two paintings, courtesy of the audacious juxtaposition – which the artist himself likens to rubbing a match along the side of a matchbox – a gesture that is followed through in the exhibition’s other three pairings of art works whose underlying morphological similarities are far less evident.

The first of these also invites a brief historical excursus. In 2008 IMMA unveiled a sculpture by Martin, Steel, commissioned by the Office of Public Works (OPW) for the museum’s East Gate entrance. This comprised three polished stainless steel cylinders placed horizontally on top of each of the entrance-way’s three imposing stone pillars. The work remained there until 2011 when it was removed due to damage caused by a motor accident. Eight years later, this work is being imaginatively reconstructed by the artist. It is intended that a new work reflecting the original will be placed within the grounds of IMMA. In the meantime, however, Barrel, 2019, a free-standing, flat-topped stainless steel cylinder of comparable scale to Steel, shares gallery space here in notably close proximity with one of Martin’s recent paintings, in acrylic on an aluminium support, which is two-and-a-half-metres tall and a little over one metre wide. Featuring a light-blue isoceles triangle stretching from top to bottom against a white ground, the work’s title is Sky, 2016, its airy aspirations complemented by the liquescent reflections of Barrel‘s mirrored surface.

If, in 1996, Fergus Martin’s energies were devoted almost entirely to painting, he has branched out considerably in the years since. For some time he was engaged in a productive collaboration with the photographer Anthony Hobbs, their work often addressing the representation of the human figure caught in the throes of some obscurely ritualistic physical performance. (A multi-panel work, Frieze, 2003 – not exhibited here – is in IMMA’s permanent collection). In contrast to these collaborative photographic works, Martin views the photographs of which he is the sole author as unburdened by intimations of narrative, at least to the degree that that is possible in non-abstract photography. In fact, while Martin’s account of his paintings’ intended effect on the viewer recalls the critic Michael Fried’s classic description of the ‘presentness’ of late modernist painting, his commentary on his photographs similarly suggests Fried’s related concept of ‘facingness’ in his account of contemporary large-scale, wall-hung photography. In both cases what is envisaged is an instantaneous giving to perception of the work as a whole.

Certainly, the idea of a photograph as a captured sliver of time’s continuum is alien to the striking conjunction of two radically dissimilar archival pigment print photos presented here. Depicted in splendid isolation, a tall ash tree’s incongruity is enhanced by its uncanny hue, a wholly unnatural shade of green that is the end-product of meticulous digital enhancement. The indefinite article in the work’s title – A Tree, 2014 – belies the entirely unrepresentative nature of its surreal subject. Ostensibly from the other side of the nature-culture divide is the suggestively titled Oedipus, 2008, a cropped photo of the coldly gleaming headlights of a sleekly-designed and well-maintained automobile. The abrasive dynamic of the abutting frames amplifies the contrast between their respective ‘landscape’ and ‘portrait formats’, as well as that between the grisaille of Oedipus versus the amped-up colour of A Tree.

This exhibition’s final pairing – though the first to be encountered by visitors on entering the corridor of IMMA’s West Wing – is between two wall-mounted sculptures in highly polished plastic, Screw Protruding Tubes (2019) and Nero Profondo (2019). Both works derive much of their power from the sense of contained density and stored energy exuded by their thin cylinders of darkly gleaming, non-traditional sculptural material with convex ends, which hug the gallery walls. Unlike the other three pairings, these two works are set some distance apart, accentuating their disparity and suggesting the passage of time and a process of gradual elaboration such as might be deemed fitting for an exhibition presented under the aegis of Then and Now. And yet, this preliminary perception is undermined by the works’ dates – both 2019, fresh from the studio – as well as the suggestion of temporal reversal in the fact that the modular Screw Protruding Tubes is effectively composed of fifteen closely aligned clones of the singular Nero Profondo. Rather than imagine the first of these works as an expansion of the second, what is evoked is a process of ultimate concentration. This intimation is apt. In spite of the considerable diversification of Fergus Martin’s interests in an expanding range of media over the past quarter of a century, this sense of concentration seems absolutely true to his work’s underlying and animating aesthetic.

Caoimhín Mac Giolla Léith, 2019.

Categories

Up Next

post digital e/AFFECT - Editors Welcome by Sophie Byrne

Fri Mar 1st, 2019