Helio-a-go-go: Sarah Hayden reflects on Dennis McNulty’s installation ‘I reached inside myself through time’

Sarah Hayden is a writer and academic who is currently researching voice in art. Here she reflects on Dennis McNulty’s installation I reached inside myself through time, a work from IMMA’s collection that draws on a diversity of materials, media and pop-cultural references to create a space that bends light, sound and time.

………………………………………………………………………………………..

I Reached Inside Myself Through Time

pleats/places

A lone voice sings out, bare and bright; it sings as though it has never known a mortal mouth. The song it sings is familiar, but as heard inside I Reached Inside Myself Through Time, is heard transformed. The recognisable is remade. Sketch of a long-known painting, radio tune reduced to scantest essence (ether-ealized), the audio is emptied of all that might distract from the fact of vocality itself. Phrases recur in proper pop-style, but each time a line repeats, its sound is slightly, near-indiscernibly altered—as though being received via differently constituted sensory processors, situated in differently structured environments. A voice sings out from elsewheres (plural).

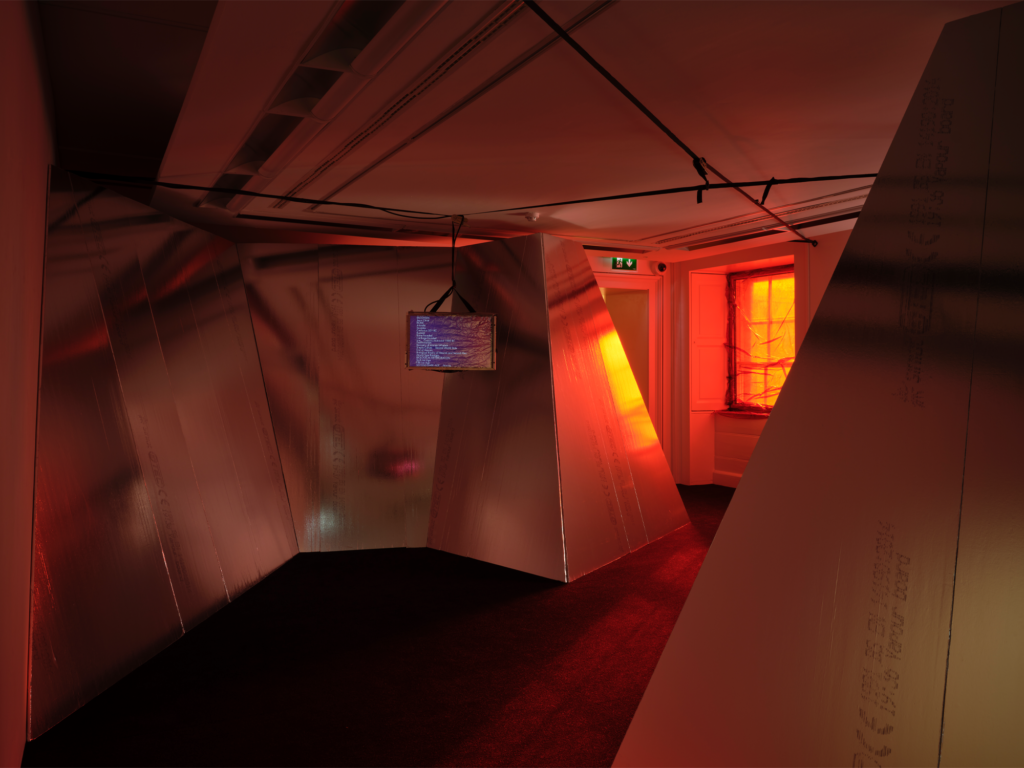

Light, within reach of this voice, behaves strangely—or has been made strange. Most of what passes into the installation space by the windows picks up a redness it owes to paint (in Lofoten) or film (in Dublin).[1] Only the lower portion of each pane is uncoated. But even what enters untinted is, like the rest, set ajangle. For inside, metallic surfaces—sometimes sheer, sometimes crunchy—interact hectically with the light. Silver makes sunlight reverberate, bouncing all-round. Light is made a chaos of distorting, disorienting sunechoes.

As a result, no body can traverse this environment without registering in the surrounding surfaces, and no viewer-listener can move through it without registering this registration of their passage in turn. At IMMA, the foil-backing of vapour-resistant plasterboard panels returns blurred reflections. Ambiguous likenesses that match blurred form for form, blurred gesture for gesture; what these return to the room are impressions with all of the detail diffused. At LIAF, peaks of craggy foil send the sun every which way at once. Rays refract, splitting forth as infinitely various light-vectors.

A temporally bounded microclimate is instantiated, warming the bodies of those who enter. Precious metal(lic)s derived from no earthly seam are deployed against their given purpose. A loud and lavish wastage of solar power is performed by materials manufactured to maximise spilled sunlight. At the infrathin site of each encounter between red ray and silver stuff: a stage-show, a sweet wrapper, a star suit. Abstraction of ‘80s space-future fantasies, these chromatic interactions singe the retina, ring metallic on the tongue. Helio-a-go-go.

I Reached Inside Myself Through Time was commissioned in 2015 for LIAF: a contemporary art festival that takes place biannually on the Norwegian islands of Lofoten, above the Arctic Circle. In the island locations it sonically cites, the materials used, the sensory effects it generates, and the circadian confusion it incites, McNulty’s installation invokes the remoteness and extreme opticality of the site that prompted its construction.

To enter IRIMTT is to invite temporal disorientation. To pass inside—as to traverse lines of latitude en route to the north—is to incite diurnal derangement. No chance [here][2] of reading shadows to chrono-locate oneself. But notwithstanding all ensuing destabilization, what enclosure there is [here] is self-consciously incomplete. And beyond the part-permeable envelope of the installation, things proceed manifestly as before, as ever. Though disappropriated of their bearings, each temporary, temporally-mithered inhabitant can yet see a way out, back to a world never altogether cut off. Alternate versions of reality, two dimensions like two notes sustained in synch. To enter [here] is to slip into a pleat. It is to occupy a fold—a context within which everything looks, feels, sounds the-same-but-different.

Inside this fold in the spacetime fabric, the voice that sings sounds the surrounds of mutually irreconcilable places. It carries into this space the echo-effects of an impossible multiplicity of different (differently constituted, differently community-convening) places.[3] Its every note is sure and steady, but the words of the song slide wild of those supplied by memory. This audible evidence of impossible translocations and transformations implies capacities—whether celestial or extra-terrestrial— that exceed those known. And so it is the confidence of the listener-viewer that is made to waver—to doubt at a level below consciousness the sensory percepts they receive.

screens/times

Meanwhile, from a strap-suspended, wrapped LCD optical interface, a curious chronology spills forth in two directions at once from a seam at its centre. Text rolls out against a background of lapis blue transitioning through the spectrum into red — rolls out in vertical counterflows.[4] What it displays is McNulty’s chronologically-sequenced listing of entries drawn from a vertiginous timeline: a huge, hand-drawn, exponentially ordered schematic prepared by the science fiction writer Olaf Stapledon as the basis for the comically vast two billion year span of his 1930 novel, First and Last Men. Up the screen flows Stapledon’s selection of significant events from the formation of this planet to 2000AD. The author’s edit of all the world’s history is idiosyncratic, ideologically constrained and inevitably culturally-myopic. Down the screen streams the pre-chronicle of what he prophesies will come next. Because of how both timestreams emerge from the same central point, distant past and still-distanter future events come into fleeting juxtaposition. Unlikely proximities result: a line that reads “FIRST MEN” is momentarily succeeded by “First Supra Temporals”, “ROME” abuts “Atomic Catastrophe” and “Cnossus, zenith” meets “FIRST MARTIAN INFLUX”.

Eschewing comment on its contents, the timeline text presents itself as authorless official record; citing no source, it draws authority from anonymity. All that can be read appears in Futura-form.[5] Issuing forth from the screen, the preternatural knowledge to which it lays claim reads as though it has not arisen from human knowledge production at all. Recalling, in its blank hyper-legibility, a text-only messaging board display,[6] it insinuates an ambivalent urgency. Its faintly milky near-translucent membrane intimates a non-specified need for protection: as though an emergency protocol has been left to loop out of time, anticipating its continued looping long into a fraught future.

A second, smaller screen shadows the timeline TV—manifesting either as dangling interface-appendage (at Lofoten) or as semi-secreted retinal after-image attached to its reverse (at IMMA). What shimmers upon this tiny monitor is the face of Morten Harket of A-ha: a portrait no more definitive than anything else in [here]. Juddering infinitesimally and constantly, it is less moving image than a reminder of mutability. And it is Harket’s voice—or a vocal track rendered down from out of Harket’s voice—that permeates IRIMTT. But just as the voice that sounds in the installation is light years from the original acapella audio-track, so the portrait of the singer is the furthest thing from a raw photo-portrait. Viewer-listeners who recognise the base of that voice are likely also familiar with Harket’s rotoscoped likeness, made famous by the once-and-forever ubiquitously played music video for A-ha’s bigger hit, Take On Me.[7] Pulled from the annals of music TV and not-quite-frozen here, Harket’s portrait summons the impossible transmutations and transpositions of its A/V source material.

In the Take On Me video, a rotoscope-drawn representation of the chiselled popstar cuts a cheeky transversal from two-to-three dimensional space. Reaching through a comic-book page. Harkett’s rotoscoped image pulls a winsome comic-reader from the live-action diner in which she mopes, into his flat, flickering, rotoscoped dimension. Like the monitor to which it is attached, this screen too is seen through a filmy membrane: viewable via the metallized PET of an anti-static bag. McNulty is an artist emphatically concerned with infrastructure, one given to giving prominence to what is crucial and structural but not ordinarily centred. If these materials summon the logistics of space-travel and other technoscientific marvels it is not because the artist makes use of any showily high-sci substances. Instead, the materials and objects McNulty puts on display are examples of inventions that have passed (as though across dimensions) from the realm of innovation to that of everyday consumer affordability—from space-bound vessels into distinctly terrestrial consumer goods. All the while, ricocheting between film-wrapped TVs, red-wrapped windows and silver surrounds, there is the song…

lyrics/ lines

Because the lyrics are so spare, and no instrumental track strings across the silences between beads/units of vocalized sound, the gaps between separately sung phonemes are exposed. The voice is made to sound especially alone—even vulnerable. Reverb tails stretch elastically and ambitiously between separately enunciated notes, but snap before ceding to the sounds that succeed them. This sustain-and-snap sequence incites in the listener-viewer a kind of sympathetic yearning. Over and over, it seems as if the note might just reach (be held) all the way across the chasm of non-sound. And every time, it fails—just. The processed voice artificially extends, then falls short. This tantalizing sequence of distinct sounds and intermitting silences can be received/read as sonic representation of the unreliability of voice as guarantor of presence. McNulty’s impulse-response processing of the vocal track produces two contrary effects. It points up the sonorous idiosyncrasies of the unique voice laid bare over the semantic import of the words it sings. And, conversely, it centres those lyrics (unobscured by any surrounding music) on a bare stage. There [here], in the space of the installation, they stand out proud in the sound-space, making themselves amply available for aural reading. [8]

McNulty’s manipulation of the audio source he mines for IRIMTT makes new lines of the modular units that constitute Harket’s sung words. Melodic enunciations have been taken apart, moved about and snapped into new phrases. Transposed into the vicinity of the song-protagonist’s “drifting mirrored mind”, lyrics that would elsewhere seem banal (“Give all your love, all your time, all your heart”) acquire new valence. Time dilates from the days and weeks of pop convention to encompass aeons. In this context of quasi-reflective surfaces, the (now “drifting, distant”) mirrors into which a classic pop protagonist might morosely gaze, amass new powers. Harket grew up in Norway (even if rather further south of the sun-slanting pole) and knowledge of his formation at this latitude lends to the lines, “The sun always shines inside myself”, and “thinking there’s got to be some way to touch the sun” an enhanced, extended plaintiveness. At the same time, the voice’s fractally reverberant tone-tails—the effects that make it sound so much on-the-move—pull against the sentiment of its invocations to “Touch me […] Hold me”. This voice that is heard to traverse diverse terrains within a single verse, denying meanwhile its origins within any tangible (touchable) body, forecloses the satisfaction of the pleas it wails. This effect is, in part, produced by the isolation of the vocal track: its presentation without the drums and keyboards that so emphatically mark beats—and so time—in the release. Set loose from the need to synch, and set about its curious, retrospective roaming, the solo voice is made temporally as well as geographically transcendent. In the original release, the line “Believe me” is followed by the wistful, “The sun always shines on TV”. When IRIMTT’s echo-enriched, ultra-transcendent Harket-voice is heard to sing “Believe me”, what comes next is one of two equally unsettling alternatives: either “the mirror’s sending me through time”, or “I reached inside myself through time”. Neither image can be comfortably envisioned. These new lines resonate with an import infinitely more epic than any found in the raw sonic/lyric material.

There’s a permutational logic to the lyrics of most pop songs, a dependence upon a narrowly delimited corpus, from which are generated repetitions with variations. Something of a similar system—albeit on a very different scale—discloses itself in the timeline that rolls out in its double/split flow on the main TV. Here, as in the course of human history, events repeat, or near-recur. By turning the contents of Stapledon’s fractally pleated tabular timeline into a list, McNulty makes apparent a cyclicality not discernible in the original document. The neat symmetries that snap into legibility when that multiscalar topology is made linear are tidy as pop-lyric rhymes. As the text unfurls from its screen-seam, Ice Ages (from the first to the sixth) recur like unevenly placed choruses. With the inevitability of a sad song that starts with a major meet-cute and then slips into a minor key, “Cnossus, zenith” is succeeded by “Cnossus destroyed”.[9] “Decline” repeatedly precedes “Recovery” and conflict is a given: the “Sino Russian War”, seeds the “Sino American War”. Like a chord resolving, the entry “Prediction of First Solar Catastrophe”, is followed, three entries later, by the realisation of that prophesy.

As today’s AI realists are already painfully aware, the future is destined to be as grim and unjust as the prejudices of those building and built into its ideological infrastructure (dataset). Equally emblematic of its era, Stapledon’s timeline text presumes upon the persistence of humanity’s predilections for violence, imperialism and war-making. Extrapolating from a colonial mentality, it predicts interplanetary invasions (“Second Martian Influx”), oppressive settlement policies (“Migration to VENUS”) and biopolitical reproductive mandates (“Breeding for Neptune)”.[10] Extending dubious fantasies of perfectibility, it predicts mutations (“Atavist Type Emerges”) and upgrades (“Abolition of Natural Death”) of the human species.

More surprisingly, the timeline is also deeply attentive to the catalytic valences of energy and extraction. While for Stapledon in 1930, the sun (“SECOND SOLAR CATASTROPHE”) looked the likeliest instigator of earth’s end, today, the vast scope of humanity’s ecocidal mission obviously presents the more clear and present danger. And yet, it is in this anticipation of energy crisis that the novelist’s projections most successfully escape his own time, and address ours. Three entries featured in McNulty’s list are headed “Power”. These record relative percentage distributions of energy generated (in future) via particular sources. According to these reckonings, the percentage of earth’s fuel-usage attributable to coal will first reduce from 50% to 10% of the entire energy supply. Then, in the wake of the predicted “End of Coal”, an enviable reliance on renewables will be instated, ultimately settling (according to the third “Power” entry) at a ratio comprising “10% Water/ 60% Tidal/ 30% Photo”.[11] Amid so much that is either horrifying or just hard to imagine, this particular prophesy of the future cannot dawn fast enough.

Watching notifications of past and future events being broadcast with equal conviction on the timeline TV, the reader-viewer-listener might be forgiven for feeling a momentary, destabilizing doubt.[12] Or, indeed, for stumbling out of the red zone, less sure than ever before of what time (hour, day, century, epoch) it is, carrying with them a residual un-ease.

Meanwhile, a lone, hyper-reverberant voice resonates in redness. Voice, like light, glances off ultra-echoic silver: sonorous singularity against transtemporal totalities. The words it sings tangle with those of two timelines that unspool in un-synced concert. A likeness twitches in unarrested animacy. A stage is set for something/s. Time runs both ways at once.

Footnotes

[1] The original proposal for LIAF had specified the use of red windowfilm, but logistical constraints on-site (off-shore) necessitated the substitution of red oil-paint, typically used to paint Lofoten fishing boats. When IRIMTT was later installed at IMMA, McNulty reverted to his original material solution. Similarly, the anti-condensation plasterboard used at IMMA also returns the work to the material state initially anticipated. Besides amplifying the work’s capacity to manifest in various forms, these substitutions also point up McNulty’s privileging of the phenomenological experience of the installation.

[2] Throughout what follows, the contingency of the temporary, geographically unfixed and temporally disorienting installation will be referred to, with square brackets, as ‘[here]’.

[3] Sites in Lofoten from which reverberations have been transferred include a dry dock, a sports hall, a tunnel, and a Nazi bunker enduring from the time of German occupation.

[4] The difference in the relative speeds of these two text litanies is (like so much else [here]) barely, subliminally perceptible—a minute variation in velocity that snags the eye, keeping the viewer-listener watching.

[5] While the Futura font’s ubiquity might make it (for some) near-invisible, other reader-listener-viewers will apprehend in the history of that typeface a polarised complex of associations. On its serif-less strokes, Futura carries myriad, mutually irreconcilable legacy-taints of its use: in the branding of NASA missions, the leaflets of diametrically opposed political parties, Bauhaus-era Utopian design features, IKEA’s proliferant production. Futura was, too, the site of an aesthetic conflict among the Nazis — its fortunes determined by the about-face on the Fraktura/German blackletter type aesthetic cast as its opposite. Having first been deemed solidly Germanic, Fraktura was later ostracised when it came to be seen as derived from Hebrew. Nearly too neatly nominally-determinist, Futura stands for what is to come, the next thing, the new world; but the same future has been envisioned in terms antipodal as night and day in temperate parts.

[6] Visual messaging boards were also used (in combination with song lyrics) in McNulty’s VMB (Keeping Up), installed in the park beside Limerick City Gallery of Art (2014).

[7] The rotoscope aesthetic was reprised, to lesser degree, in the opening frames of the video for The Sun Always Shines on TV. One further curious cross-reference: in the Take On Me video, the rotoscoped motorcycle race is triggered by the firing of a starter pistol. The same device was used by McNulty in the larger of these spaces to produce the reverb tails then applied to the audio.

[8] Featured prominently across McNulty’s back-catalogue, song lyrics are also used as material in Maybe everything that dies… (2013), VMB (Keepin’ up) (2014), Running up that building (2015).

[9] On the meet cute trope and some of its early uses, see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Meet_cute

[10] In Stapledon’s timeline, as in the less speculative chronicles of human history, it’s a man’s man’s man’s man’s world. This wholly predictable gender bias manifests not just in the use of the collective noun as standard but equally in the naming of individuals: a cast of hoary regulars: Greek philosophers, Shakespeare, Newton, Kant, Darwin, as well as Confucius, and Jesus Christ.

[11] The Lofoten archipelago has historically been fuelled by its fishing (and more recently, tourism) industry and has to date been protected from oil and gas extraction. However, the endurance of this protected status is the subject of considerable, politically fraught debate. IRIMTT was first installed at Lofoten in 2015. In the same place, two years later, a manifesto for fossil fuel divestment and an end to hydrocarbon exploration was written and opened to signatories the world over. The Lofoten Declaration has since been signed by over 600 organisations in 76 countries. Temporal incongruities and spatial coincidences continue to thicken the atmosphere of the work.

[12] In Stapledon’s chart, and as McNulty faithfully re-presents it on-screen, an interrogative uncertainty is ascribed to certain events of the deep past (“First Reptiles?”, “First Mammals?”), but no such typographical indicator of dubiety attaches to projections post-2000 AD.

Categories

Further Reading

Exhibition Design

The Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now: The Anthropocene

Design plays an intricate and emotive role throughout the galleries of the museum-wide exhibition The Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now. From raw red tones and icy cold blues to the textured surface of the han...

Up Next

'Reflections on a Radical Plot', Charlotte Salter-Townshend in conversation with Clodagh Emoe

Tue May 31st, 2022