Radiating Shadows – James Merrigan interviews Brian Teeling

In this magazine article, James Merrigan interviews Brian Teeling about what inspires and fuels his multidisciplinary practice.

Brian Teeling is an invited IMMA artist working in one of the four studios generously gifted to IMMA by the Dean Art Studios on Chatham Row in Dublin’s City Centre. Joining this dynamic creative community is an exciting opportunity for both the artists and for IMMA.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

JAMES MERRIGAN: I scrolled through close to 1500 posts on your Instagram account. Over that 7 years of photographic documentation of a life lived, loved, and experienced, I discovered the mirrored self-portrait as a perennial haunting presence as early as your fourth Instagram post-dated 13 December 2015. Can you elaborate on the photographic self in your work, specifically as a photographer, which manifests in a panoply of mirrored objects, from the car mirror, elevator mirror, bedroom/bathroom mirror, and TV screen?

BRIAN TEELING: I’d love to be able to say something delectable about them, like “I’m cruising my reflection”, but the reality is that the self-portraits began as primarily thoughtless photos, used to fill frames at the end of a roll of film.

When I look back at them now, I can register that I’m recognizing myself at that moment in time, in the event. It makes me think of what Slavoj Žižek has to say about the ‘event’: “…event is not something that occurs within the world but is a change of the very frame through which we perceive the world and engage in it. Such a frame can sometimes be directly presented as a fiction which nonetheless enables us to tell the truth in an indirect way.” These self-portraits can be situational, being present to the power of a kind of political energy of the body in space and time. I can see flesh and blood, I can determine how I was feeling. There’s also a weird balance between slight narcissism and an emotional register for a life previously lived. I wish I could reach into these photos and reassure myself sometimes, but other times I think “Oh my god, my arm looks great there.”

Recently, I’ve been thinking of them as diffractions, and maybe these are diffracted versions of myself. Radiating shadows that have their reality in the past, somehow stuck in some unremitting universe. Generally, I like to think of photos as pathways to other realities.

JM: You said in casual conversation before, that you felt that knowing you personally led to knowing your work. Can you talk about the photograph Shower-Time (Southend) October 2018 in relation to this knowing you, knowing your work thesis?

BT: There’s this interview with Félix González-Torres from Flash Art by the critic and curator Bob Nickas. In the interview, Bob asks Félix about his audience and posits a lovely idea that has stuck with me. “I believe art is made for no more than five or six people you know, and anyone else who gets something out of it, it’s just extra.” I love this idea from Bob. For me, it reaffirms this idea of “to know me is to know the work”. If you didn’t know me and you saw the Shower-Time photo, you could read it in a certain way in terms of a contemporary domestic scene, but if you knew me better you would understand what my relationship with my ex-boyfriend Scottee was like, who really crystallised ideas around the working-class experience for me in art. Scottee is an incredible artist, performer, activist and he helped enshrine the belief in vocality, but also presence and embodiment just through the process of making work. It’s really important to me.

This photo comes from us waking up in the morning — I think we just had sex — and getting ready to head out into Southend where Scottee was living at the time. It was an uncanny situation for me, primarily because it’s something that I’ve never had in any of my previous relationships. I’ve never had this domestic scene, just doing unexciting things, like brushing our teeth and having a shower. This was included as part of A Vague Anxiety (2019) at IMMA and is one of my favourite works I’ve made. Much like Scottee, it means a lot to me.

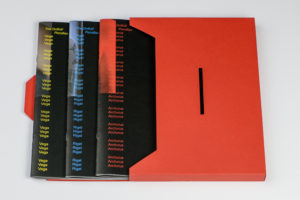

JM: Your most recent print publication The Drift /// Parallax, what you describe as a “triptych of publications based on the stars Arcturus, Rigel and Vega”, is an experience of chromatic and lyrical elegance. Why has text become more than an element within your photography, but a supplementary excess outside your photography?

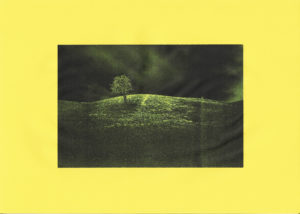

BT: At the beginning of the lockdown in 2020, I was feeling ‘uncentered’. I believed I had this enormous burden that I should be taking advantage of all that free time, but I was just burned out. I was working two jobs, full-time in retail and full-time with my practice. After a period of not doing much other than going for long walks and re-watching The X-Files in its entirety, I started looking through my archives, to see if I could find patterns, resonances, or anything that would lead me somewhere. I collated all the images that had a sonorous quality and began to print with them. There’s an easy connection between memory and photography, and I wanted to address the fallibility of our memories by purposefully and inadvertently degrading the photos through printing, scanning, and reprinting. Three bodies of work emerged from this process of retrospection, and what is called “anamnesis”, when you confront the fallibility of memory and recall. The Disintegration works, which I exhibited as part of Speech Sounds (2022) at Visual, Carlow, were large-scale text works, comprising multiple sheets of paper, intended to disintegrate over time. Lastly was my book The Drift /// Parallax, which is a combination of text and image.

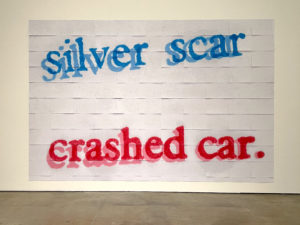

Text work has been present since I started captioning photos. It feels right that it’s more visual in my work now, less of a shadow aspect, and more pronounced. The combination of the image and text is where I feel there is a power, where there’s an explosion of meaning. I could feel that when I was assembling ‘The Drift /// Parallax’. There was so much more I could infer, or obfuscate behind the ‘lyrics’ combined with the photos.

JM: The experience of sexuality and class are continually repeated in the literature that accompanies your exhibitions and printed projects. When I think of these two experiences, I think of the working-class philosopher Pierre Bourdieu, and what he defined as “Habitus”. Can you elaborate on the experiences of masculinity and queer working-class identity within your work? Not just as embedded content, but how it manifests as colour (such as red)?

BT: Sometimes, I want to disregard those labels, as I feel discomfort in being pigeonholed. But in art, you have to be able to demonstrate who you are, and the best way to do that is to be truthful to your lived experience because it’s what you embody when you make work. My work is inherently masculine, queer, and working-class because that’s who I am.

I feel that identity is too often elevated over lived experience. Ornamentation is in a higher regard, simply because people believe in the truth of aesthetics, rather than the reality of ‘habitus’. What I mean by this is that identity is something that can be commandeered, purchased, and presented as reality, rather than something gained through a lived experience. This is an implosion of meaning. We see this all the time in fragile men dressing like CEOs or ‘tender-queers’ policing others online (while working for arms manufacturers).

Everyone has a personal relationship with colour. Red for me, is personal. I can trace it throughout my life. The colour of Eric Cantona’s Manchester United jersey, the brake-lights of every car that went through my Dad’s garage, the colour of the light emanating from my bedside lamp, the supposed enemy of every photographer.

JM: Your ongoing “c-space” installation in the toilets of The Dean Art Studios Dublin is (to my mind) one of the most visceral and sympathetic off-site artworks I have experienced in recent times. It’s site-specific, intimating a cruising space for casual sex, with the formal suggestions of glory holes and voyeuristic car mirrors under heavy red lights. It invokes the words of the artist Luis Camnitzer, in his text work This is a Mirror, You are a Written Sentence…

BT: I’ve had this idea around cruising for quite a while, where I’m overlooking the transactional part, and trying to think more romantically about it. Maybe this is a result of being single for so long, but I think the idea of connecting with someone on a greater intimate level, even for a moment, is appealing. And that connection doesn’t inherently have to be just sexual, maybe there’s something deeper, emotionally, spiritually. This was the entry point for that work, which allowed me to collide with other aspects into one space. The car, the text, the colour red, the mirrors, the cosmos, the glory holes.

The works present in that space all address looking, observing, location & distance. Car mirrors, vinyl, light-fixtures, and song lyrics, they all have a familiarity. I like the idea of taking these standard objects and shifting them slightly, into a new realm of thought. You’re forced to address your relationship with these items, establish a new meaning, and reinforce an old one. It kind of mirrors what I want to do with cruising. Shift the meaning.

There’s one work I wanted to include in that space but didn’t have time to realise it. It was a hidden speaker within a cistern, which would have a playlist of 100 ambient songs and film soundtracks, all without lyrics (except ‘Outside’ by George Michael as a kind of Easter Egg). The idea being that every time you enter the space to cruise, it’s likely you’ll hear a different song, and you’ll have a different experience. I like the idea of this being shared by people who visit the space, unaware of its intent, or inherent possibilities. This unrealized work would have been called ‘River Fragments’ after Heraclitus. “No man steps into the same river twice, because the river has changed, and so has the man.”

JM: Recently you brought up Roland Barthes’ A Lover’s Discourse. I searched for my copy at home and came across a segment I underlined twenty years ago, at a time when I was trying to find images to suit my desire:

“It has taken many accidents, many surprising coincidences (and perhaps many efforts), for me to find the Image which, out of a thousand, suits my desire. Herein a great enigma, to which I shall never possess the key: Why is it that I desire So-and-so? Why is it that I desire So-and-so lastingly, longingly? Is it the whole of So-and-so I desire (a silhouette, a shape, a mood? And, in that case, what is it in this loved body which has the vocation of a fetish for me?”

What do you think about when you read this?

BT: The ‘Image’ for me is a person who you are in love with. Deep, romantic love. Swimming in their lake.

That passage really speaks to me. I think about an ex I was once in love with, and the amount of self-reflection I had done over that period of my life. Why did I desire him? Was I in love with the idea of him, rather than the actual person? I love that this passage invokes ideas around photography, snapshots, visuals, and framing. I think that’s why I’m drawn to Barthes’ work so much.

JM: When I think about your work in relation to love, and then Félix González-Torres’ work in relation to his lover Ross, I wonder if Félix’s work was doing two things at once: one, it was made out of the love he felt for Ross, and two, it was motivated by the anxiety of losing that love while Ross was dying of AIDS? So perhaps the haunting love references and sensations in your work are about the absence and yearning for love, which makes it all the more present?

BT: Félix’s work Untitled (Portrait of Ross in LA) is incredibly powerful and my favourite example of love in his work. You can feel it, it’s real. The power of it, how he memorialises him, the personal aspects of Ross’ sweetness, and the tragedy of AIDS. He puts so much meaning into it, it’s transformative and heavy with emotion.

In my work, I feel the absence. I yearn for that love, for someone to memorialise, to be vulnerable with. Those ideas can be channelled into other works, without necessarily being about love. Like absence. I focussed on that for Declan Flynn in Dublin where I made ten different aspects of Declan and his life. Each aspect was a distillation of a part of his life. His absence is present, his presence is absent. This in portraiture I find interesting because you can still tell a story about someone, and visualise part of who they are, without photographing them directly.

JM: You used the word “hauntology“ in reference to your own work recently. But when I look at your work I don’t see the ghosts of the past, but the ghosts of the present reality. Can you name anything you are haunted by in choosing, taking, and curating your work?

BT: When I talk about hauntology, I’m considering it in the same way that Mark Fisher did, in terms of being haunted by a future that will never come to pass. That future was having my father present in my life. He is the haunting presence. He’s a mechanic. You can see that reflected in the cars that keep appearing in my work. When I was younger, I felt I would become a mechanic or involved in cars in some way. I spent a lot of time in my Dad’s garage. The memories from that space are tinged with the scent of new car smell fresheners and exhaust fumes, his blue oil-stained overalls, and the endless supply of broken cars in need of repair that came into that garage. We don’t speak anymore, which is tragic, but it’s something I’ve come to accept. I idolised him growing up, and would look forward to being collected by him after school. Every day he would arrive in a different car. I remember one time he picked me up in a huge Volvo estate that was painted white with big leopard spots on it. It was so bizarre, but I remember him being totally unfazed by it. He’s his own person, and unconcerned with the opinion of others. We’re quite similar, so that’s probably why we clash.

JM: Before we get to my final question about love in your work, could you describe the body of work you are currently developing entitled “Black Mesa”. My initial response to the images you shared of self-portraits, car crashes and Audi rings graphics is that they register as spectres for something much darker, something much emptier?

BT: Black Mesa is a collision of photographic work that addresses ideas around depression, poles of inaccessibility (Point Nemo), the International Space Station, and car crashes. These collisions are made from instant film photos, found images, and graphics. This work exists as digitally printed flags, large-scale vinyl, clothing, aluminium and framed c-type prints, and some text work.

There’s a truth at the core of this work. It uses a mix of the personal with the fictional in order to express a desire to be rid of depression. To crash and relocate a depressive state of being into an inaccessible point, and submerge it with the broken decommissioned satellites beneath the Pacific Ocean, to both extend and subvert its weight and claustrophobia.

JM: The question of love was something I had planned as a final question (for now), but somehow love is the thing that seems to keep coming to the surface, especially in your references to the love behind Félix González-Torres’ work, and the absence but search for love in your own work. Any last words on love in your work?

BT: Love for me in my work is represented by meaning. Love is the meaning, the meaning is love. I don’t think I can make work without it, or can make meaningful work (to me) without it.

Find out more about Brian’s work through his website or at imma.ie

Find out more about James’ work here

Brian Teeling – @brianteeling

James Merrigan – @james__merrigan

Banner Image Credit: Brian Teeling, Self-Portrait, Karim’s, November 2022, Photograph

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

About James Merrigan

James Merrigan began writing critically on art in 2008 on the advent of the global financial crisis. The title of his first online writing moniker Billion Journal was a statement of his belief that money is the opposite of culture. For over a decade he has continued to make critical statements via different online and self-print entities, the most recent being Small Night, which works with artists on antagonistic and subversive image and text publications and exhibitions, screen-printed in his independent studio based in Waterford City.

Categories

Up Next

Witnessing 'Yellow' by Paola Catizone

Sun Jan 15th, 2023