Paula Rego: Empathy is a Moral Force

Patricia Brennan, Visitor Engagement Team at IMMA and PG student at TCD, continues to engage with the art of renowned realist painter Dame Paula Rego, in an introduction to Rego’s solo exhibition Obedience and Defiance currently at IMMA. This second of a two-part text, pivots on Rego’s engagement with human rights and gender politics from the millennium to the present day. Serendipitous conjunctions with writers and artists – past and present – are observed.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Tales of mystery and imagination

“The picture begins to tell you what has happened”[I]

This second part of an introduction to Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance, curated by Catherine Lampert, looks at some of the great works from the past twenty years of the artist’s oeuvre. There is, notably, a dramatic increase in scale, while the artist continues the interweaving of gender politics with storytelling, further informed by an awareness of the old masters of European painting.

Rego has followed her own particular research, often closely connected to the Portuguese folktales which she reinvents and upturns with spectacularly unnerving results: “The Portuguese have a culture that lends itself to the most grotesque stories you can imagine”.[ii] Never purely illustrative, the work takes off in a different direction from the point of reference, shaping an alternative vision, whether Rego is reimagining a folktale, a Disney classic, or Jane Eyre.

The documentary film made by her son Nick Willing in 2017 shows his mother’s studio populated by the grotesque fantasy figures made by Rego, sometimes aided by her son-in-law, Ron Mueck. (They appear in works such as The Cake Woman (2004) and The Pillowman (2004)).

Forbidden things

A friend to poets, Rego has referenced literature and nursery rhymes in addition to her beloved Portuguese folktales. In 1997, the painter began a series which was inspired by – yet diverges from – the nineteenth-century Portuguese novel The Crime of Father Amaro by Eça de Queirós. (A story of seduction, love and betrayal, the book became a film in 2002 starring Gael García Bernal). The title, The Company of Women, puts me in mind of John McGahern’s[iii] best known novel, Amongst Women. Rego and McGahern address the dysfunction in Portuguese and Irish societies respectively, and how the damage is handed down through the generations. Just as Rego’s women sometimes punish the men they love, McGahern’s central character, Mahon, finally becomes as tortuously caught as his daughters in a web of co-dependency.

Retribution

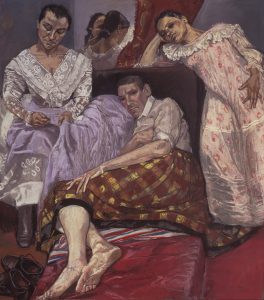

In The Coop (1997), from the same series, a harsh and glaring light illuminates the power struggles between genders and generations in a patriarchal society, including the withholding of love and acceptance as a form of control. Amélia is pregnant, with very few options; deserted by her lover. “Who else has painted the world from a female point of view in the manner described by Paula Rego?” asks the Guardian’s Will Gompertz. These large scale works resemble taut, charged and theatrical tableaux. Amélia does not go unavenged in the painterly finale to the tragic epic. Angel (1998), presents us with an implacable heroine in the mould of Lady Macbeth, armed with a dagger and holding in her other hand a sponge, a traditional symbol of the crucifixion.

“Painting pictures is like being a man”

Continuing the theme of religious iconography in Joseph’s Dream (1990), Mary – standing in for Rego herself – is portrayed as a painter. The artist chose as the other sitter her companion; the writer Rudi Nassauer, in a tender tribute. According to Simone de Beauvoir, the patriarchy reduced Mary to being a mere conduit; a means of silencing women. Alternatively, Joseph’s Dream presents Mary as the autonomous artist and creator. As Marina Warner said “it is pictures and objects that speak loudest”[iv]. In 2002, by request of the Portuguese President, Jorge Sampaio, Rego made a series of paintings on the Life of the Virgin for the chapel of the presidential residence, the “Palácio de Belém” in Lisbon (not in this exhibition). In those scenes Mary is portrayed as never before in European art; a fully corporeal teenager. This is in contrast to the otherworldly portrayals of Mary since Giotto, and particularly the serene Madonnas of Murillo. (In 1991 Rego completed a rather different commission from the National Gallery based on the Life of the Virgin).

Courage in adversity

This show stopping triptych is a complete reworking of Marriage à Mode by William Hogarth, (whose prints are in the IMMA Collection). Hogarth showed professional acumen when he disseminated prints of his paintings to reach a wider audience, and Rego too, is renowned for her accomplished and often discombobulating graphic work. (A selection of Paula Rego prints in the IMMA Collection can be viewed online). Hogarth’s series famously satirises the hypocrisy of polite society with a ribald savagery akin to Rego’s. Hogarth ends his series with the bridegroom shot and the wife left with nothing but unpaid bills. Contrarily, Rego’s final panel shows the husband’s weakened body supported by his resilient wife, in a reversal of traditional gender roles. The Shipwreck has been compared to a traditional Pietà, and was, in part, a way for the artist to come to terms with the loss of her husband to catastrophic illness.

Calling out injustice

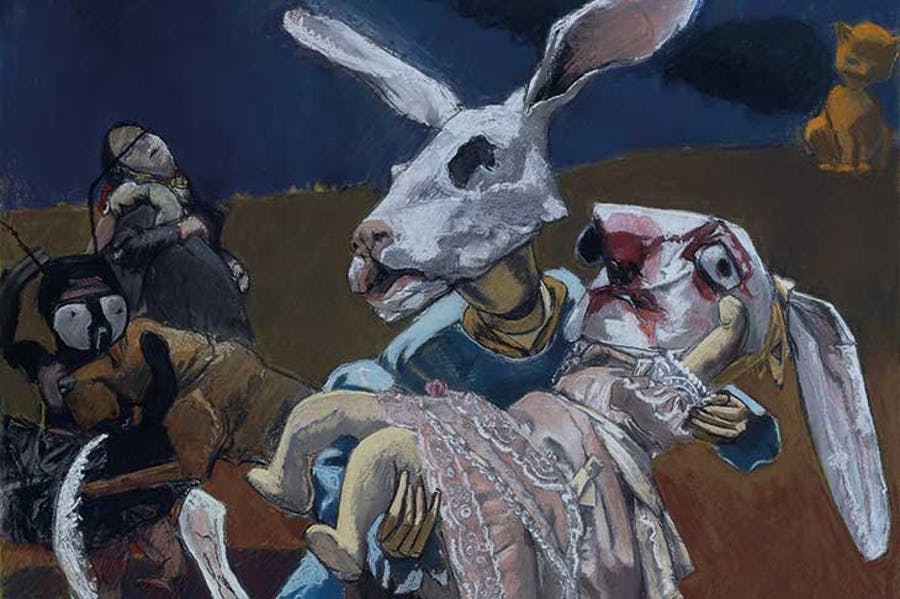

A powerful voice for the poor, Rego’s War (2003) was based on a photograph of a little girl being carried from the rubble in Basra, during the Gulf War. Rego’s use of animal figures underlines the vulnerability of the protagonists and the awful poignancy of civilian deaths in war time.

Upending tradition

Rego’s works mentioned here, recall in their aspirations and scale, the paintings of the past which she admires by Goya, Zurbarán, Murillo, Velásquez and of course Hogarth. Rego confided in Catherine Lampert that going to the Prado gives her courage. Rather than consciously analysing the paintings there, the artist has said that she prefers to be with them, “and that contaminates you; I’ll kind of catch it … Photographs do not have presences like that. These are like people or like humans or animals that are alive, so I do like being with them.” [v] Rego never works from photographs, always from the model or from imagination.[vi]

Subversion

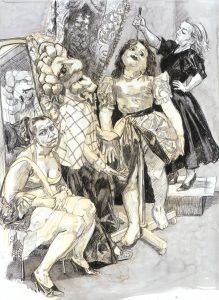

Rego claimed that seeing Martin McDonagh’s play, The Pillowman, changed her life. Subsequently Rego and McDonagh became friends. The playwright’s wickedly dark sense of humour is in tune with Rego’s. In addition, they share a propensity for calling out brutality and hypocrisy within communities and the state. The Pillowman raises questions about art, power, family and religion, according to one review. However, Rego’s huge triptych is not an illustration of the story; there is an echo of her beloved father’s depression in the huge immobile figure of the Pillowman.

“You punish people with drawings”[vii]

In her series on FGM (and in the abortion series) Rego avoids gore. Instead, she makes us imagine another’s experience, polarised by a choice between outward conformity or the truly unthinkable; social ostracism.

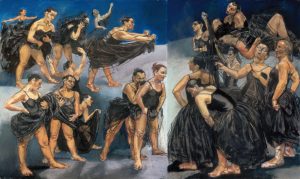

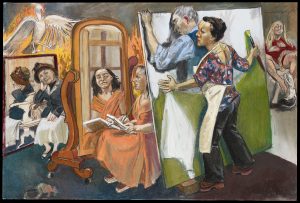

Painting Him Out (2011) is, as Catherine Lampert has pointed out, a playful undermining of the traditional gender roles between painter and model, as the female artist determinedly removes the male presence from her studio. Rego’s creative drive matches any man’s; her breakthrough in the UK came with the 1988 exhibition at the Serpentine. That same year, Rego was nominated for the Turner prize and her largest painting to date, The Dance, was bought by the Tate.

“It isn’t nice in my mind”[viii]

As noted in part 1 of this article, Paula Rego has much in common with Lucian Freud, another great painter of the human condition now at IMMA, yet there are stark contrasts. Freud was a portrait painter; Rego, for the most part, is not. Her work is political; his reflects a private world. Freud (usually) painted individuals, and even his groups and double portraits convey a sense of separate lives. Rego, on the other hand, implies the complex dramas of interdependence which are always personal, always political.

Cometh the hour

At eighty-five, Rego’s output continues to be prodigious. The narrative tension deployed in the work, a sense of time suspended in the moment before the crisis, makes each piece and every series irresistibly compelling. Not long before he died, Victor Willing wrote to Paula Rego: “Trust yourself, and you will be your own best friend”.[ix] Now internationally acknowledged and heaped with honours, Rego is bravely and defiantly herself; a woman who will not be silenced.

[i] Catherine Lampert, p. 14, “This Dark Corridor it Begins to Light Up”, in Paula Rego, Obedience and Defiance, ed. A. Spira and C. Lampert, pub. by MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, 2019.

[ii] https://www.theartstory.org/artist/rego-paula/life-and-legacy/

[iii] A haunting pencil portrait of McGahern by the painter Patrick Swift and the story of their friendship can be accessed at http://painterpatrickswift.blogspot.com/1970/03/bird-swift-john-mcgahern-writer.html

[iv] Kathryn Hughes: “Rereading “Alone of All Her Sex” by Marina Warner, The Guardian, 23rd March, 2013. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/mar/23/rereading-alone-of-all-her-sex

[v] Paula Rego interviewed by Catherine Lampert, 18th September, 2017.

[vi] Rego spoke about the challenges of portrait painting when Germaine Greer sat for her (a commission from the National Portrait Gallery). https://www.bl.uk/collection-items/paula-rego-on-her-struggle-to-paint-a-portrait-of-germaine-greer The square format and informal pose of the Greer portrait share a similar approach to Lucian Freud’s canvases from the ’60s through the ’80s, for example some of his portraits of The Big Man, 1976-77.

[vii] https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2009/aug/22/paula-rego-art-interview

[viii] https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/nov/11/paula-rego-it-isnt-nice-in-my-mind

[ix] Paula Rego, Secrets and Stories, directed by Nick Willing, produced for the BBC by Kismet Film Company, 2017.

Categories

Up Next

Paula Rego, a life between Lisbon and London

Sun Oct 18th, 2020