Paula Rego, a life between Lisbon and London

Patricia Brennan, Visitor Engagement Team at IMMA and PG student at TCD, engages with the art of renowned realist painter Dame Paula Rego, in an introduction to Rego’s solo exhibition Obedience and Defiance currently at IMMA. In this first of a two-part text, there are references to the political context and influences of the artist’s early life and on her works up until the millennium.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………..…

Darkness in Europe

“If you look the devil in the face you’re less frightened of him”.[I]

In Ireland in 1932 de Valera strode to centre stage as Taoiseach and Salazar came to power in Portugal, against the backdrop of fascism in Europe. While Salazar brought greater economic stability to Portugal, it was at the cost of curtailing civil liberties. The Estado Novo would not be toppled until 1974, and over here, de Valera cast a long shadow. The role of women in the home was enshrined in both the Irish and the Portuguese constitutions, and after a long struggle, complete suffrage was finally won in Portugal in 1976. Born three years into the Portuguese dictatorship, Paula Rego has tackled political issues which festered under oppressive regimes, but also her own personal demons, to bare the hidden lives of women. Rego’s works are often disquieting, undeniably powerful, drawing inspiration from newspaper stories, cartoons, and folk tales, as well as the artist’s inner life.

A liberal education

Paula Rego was born in Lisbon and spent most of her early years in Cascais, where now stands the Casa das Historias Paula Rego. From the age of 10, Rego was schooled through English at St. Julian’s, in Carcavelos, which then as now placed great emphasis on the arts in education and was the competitor of the Irish run St. Dominic’s, (where coincidentally, I taught art briefly in the late ’80s). Her father, Jose Figueiroa Rego, was “an immensely kind and liberal man who tried to give me my freedom”. They shared a passion for film and music. Rego’s mother, Mariade São José, is remembered by her daughter as “quite a lady; I learned from her the pleasure of clothes. She had a marvellous eye for painting.”[ii]

The life room

Rego entered the legendary Slade School of Art[iii] at 17 while William Coldstream was director. As a visiting tutor, L.S. Lowry was encouraging of Rego whereas Lucian Freud was occasionally glimpsed slipping in and straight out of the life room, which was at its zenith, with Euan Uglow a fellow student. (If I had a time machine, I’d go straight to that life room with those three great painters of the human form: Freud, Uglow and Rego). The latter remembers at first being shocked at the sight and smell of naked people, but Rego learnt a discipline in drawing which has served her well as a figurative artist. She particularly enjoyed the print room, where she could escape to draw anything she wanted to. In 1954 Rego won the coveted Summer Composition prize. Her piece was titled Under Milk Wood, a reference to Dylan Thomas.

Soul mates

Rego fell in love with a fellow student, the brilliant, charismatic and handsome Victor Willing. When Rego became pregnant with their first child, her beloved father drove all the way to London to talk things over and took his daughter home, stopping in Paris for new clothes. Willing followed after and the young couple settled for some years in her parents’ summer house at Eiriceira.

Defiance

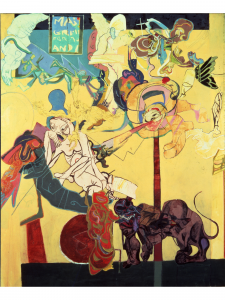

Rego had her first solo show in Lisbon in 1965, at the Galeria de Arte Moderna, with works which satirised the political establishment.[iv] Manifesto for a Lost Cause, 1965, was about her father, and his frustration with the Salazar dictatorship. Rego’s work from the ’60s threw a sidelong glance at Juan Miró, who likewise satirised dictatorship in his Barcelona series and in his marvellous theatrical costumes for Alfred Jarry’s play, Ubu Roi.

Democracy

Freedom came with the almost bloodless Carnation Revolution in 1974, but too late for Rego’s father, who had died in 1966. In the same year Victor Willing was diagnosed with MS. Despite these personal difficulties, Rego managed to get herself into the studio to work, and she continued to exhibit in Lisbon and Porto, and had a solo show in London in 1981, at the AIR Gallery. Her reputation outside Portugal grew; in 1985 Rego had a solo show in London at Edward Totah and another in New York.

Drawing things out

By the late eighties, Victor Willing was very ill indeed. Rego would roll up the large sheets of paper she worked on at the studio and bring them home for his opinion. The artist has acknowledged Willing as her mentor during their life together. Her paintings, especially from those days in the late ‘80s, show the conflicting emotions and dramas of her personal life. Rego has never shied away from the truth, and gives all sides of the power struggles that exist even in the most loving relationships. The Family, 1988, is replete with tension as much as affection, as the girls care for their father even as they seem to overwhelm him in their efforts.

A new life

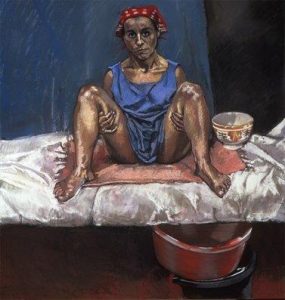

The Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian in Lisbon, a great support to the artist from the sixties onwards, gave Rego a retrospective in 1988, the same year in which Victor Willing passed away. In one of her most extraordinary series, the Dog Women of the early ‘90s, Rego used pastel to great effect, and dealt with her own feelings of loneliness after her husband’s death. Pastel felt more immediate, more like drawing than painting. Rego’s renewed interest and ambition with regard to her drawing seems to intensify from here onwards, and she has worked increasingly from the model, often Lila Nunes, (Willing’s carer). The choice of pastels for many major works in the last 30 years points to this stronger emphasis on drawing over painting, although both elements are there in the work.

Dog Women

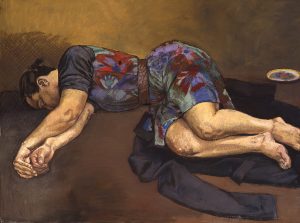

In Sleeper, from Rego’s significant Dog Women series, the girl rests on her man’s coat like a faithful dog seeking comfort. As my colleague Sandra Murphy pointed out to me, Sleeper can be compared to Double Portrait by Lucian Freud, with human and dog entwined and somnolent. Whereas Freud is focused on the unique biology of two living creatures, Rego emphasises character.

Paula Rego depicts the lives of women primarily; her series on abortion in particular bears witness to the pragmatic way that ordinary women deal with a taboo subject and makes us share in their experience, without rhetoric or judgement. Curator of the exhibition Catherine Lampert notes in the catalogue: “the work is born of everyday reality and a constant negotiation with life as it is.” The series began as a personal response by the artist to the defeat of the referendum on the right to choose in Portugal, 1998. As in Ireland, it was a deeply divisive issue in a traditionally Catholic country. Some of Rego’s images were reproduced as part of the pro-choice campaign in 2008, when the referendum was passed to allow limited access to terminations. Later graphic works on the issue of female genital mutilation are equally uncompromising.

Transcendence

Rego’s creative drive is astounding, particularly in the face of personal adversity, and her ability to marry the private with the political makes Rego constantly relevant as an artist. Rego’s courage and integrity is evident in her choice of subject matter and the determination to speak her truth, and in the authority, power and conviction of her draughtsmanship. The artist’s skilled hands sift through the discomfiting truths of her life, and ours. With Lucian Freud and Paula Rego at IMMA this year, we have the male and the female gaze, and two of the greatest British realist painters of this or any century; both born in Europe.

Part 2 of this article will examine several of Rego’s monumental series. Paula Rego: Obedience and Defiance continues at IMMA until 3 January 2021.

[i] Desert Island Discs, BBC Radio 4, 1992 https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p00943vs

[ii] https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2004/jul/17/art.art

[iii] For a great read which addresses an earlier and equally celebrated time at the Slade, I recommend Pat Barker’s novel “Life Class”.

[iv] Paula Rego, Obedience and Defiance, edited by Anthony Spira and Catherine Lampert, pub. by MK Gallery, Milton Keynes, Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin, 2019.

Categories

Further Reading

Exploring Bharti Kher’s Virus Series

The exhibition A Consummate Joy by Bharti Kher was due to open to the public at IMMA on Friday 13th March 2020. This was the day public buildings were closed due to concerns about the spread of COVID-19. Thi...

The artist as flâneuse, a walking cultural commentator

Beth O’Halloran, Visitor Engagement Team at IMMA/lecturer at NCAD, looks at the transgressive role of female artists as cultural ethnographers – in particular the artist as flâneuse. Included are references ...

A Vague Anxiety by Seán Kissane

The exhibition A Vague Anxiety at IMMA invited a range of emerging Irish and international artists to consider the macro and micro anxieties that inform a certain experience of the world today. In this essay...

Up Next

The artist as flâneuse, a walking cultural commentator

Tue Sep 22nd, 2020