Karol Radziszewski: Queering the Archive in Eastern Europe

Putting Queer Archives to Creative and Public Use

It can be said that archives act as repositories of collective memory and sites of knowledge production. They propose how we account for the past and provide a framework for understanding and defining contemporary life.

In association with IMMA’s CHROMA programme, on Saturday 1 February 2020, we will present a special series of events, titled Queering the Archive, to look closer at the private and public nature of queer archives and how these can be put to creative and public use. On the day we will uncover the methodologies of archive reclamation, disruption, interrogation and care, that foreground the interpretative work of Irish and international artists and activists.

While certain progress has been made with the legislation of LGBTQ + civil rights in Ireland, structural inequality, the invisibility of certain narratives, and the exercise of political power continues to interfere with the inheritance of our culture and the mediation of our history and identity. In the face of increasing polarised debate surrounding civil rights and liberties of LGBTQ + communities in Eastern Europe and beyond, we invite Nathan O’ Donnell, Research Fellow, IMMA/TCD to introduce the important work of Polish artist Karol Radziszewski. Radziszewski continues to forefront the public use of queer archives in Poland, despite gays, trans and other forms of queer lives and identities are now being highly contested and censored.

Artists can offer us current day reflections on the importance for us all to build international solidarity for a queer future of a global reach, and as O’Donnell’s text explains Radziszewski’s activist project ‘Queer Archive Institute’, demonstrates how archives resonant far beyond the primary function as records of the distant past.

O’Donnell’s article prefaces Karol Radziszewski’s talk at IMMA on 1 February 2020. More programme details here >>>

Sophie Byrne, Talks and Public Programme, IMMA.

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Karol Radziszewski: Queering the Archive in Eastern Europe

I arrived at BWA Gallery in Warsaw on a rainy afternoon in Spring. I was here to meet the artist Karol Radziszewski, who greeted me on the doorstep, under the colonnade on Marszałkowska Street, and showed me inside. The gallery was closed, deinstalling, but a number of his works were still hanging on the walls, from a group exhibition that had just finished (one of a series of city-wide exhibitions as part of a gallery-sharing initiative, Friend of a Friend).

These works, a set of acrylic paintings from his recent series 1989, feature simple line figures that have been copied (and magnified) from his own scribbled childhood drawings, mapping aspects of his own life and memory out onto histories of protest and queerness, the fall of communism, and the emergence of the modern Polish Republic. There are figures in drag, princesses; one canvas features the symbol for Solidarność, the great protest movement that originated in the Gdańsk shipyards in the early 1980s. There is also a figure resembling the leader and ‘hero’ of the protests (and later President of the new Republic), Lech Wałęsa, transfigured, queered – a deeply subversive gesture in contemporary Poland.

These paintings, like other of Radziszewski’s works, draw what are considered ‘dissident’ sexual identities into the conventional domestic sphere. His ‘fag fighters’, for instance, are a fictional band of violent queer guerrilla activists in pink balaclavas, the subject of several films and interventions; in Fag Fighters: Prologue (2007), however, we see the balaclavas being knitted by his grandmother. In his work, Radziszewski brings aspects of queer subculture into the sacrosanct realm of the Polish family. This is not, as it could be, a normative gesture. Radziszewski does not advocate assimilation; the subversive antagonism of queerness is not rendered tasteful or easy to consume. The viewer is simply invited to sit with this disparity.

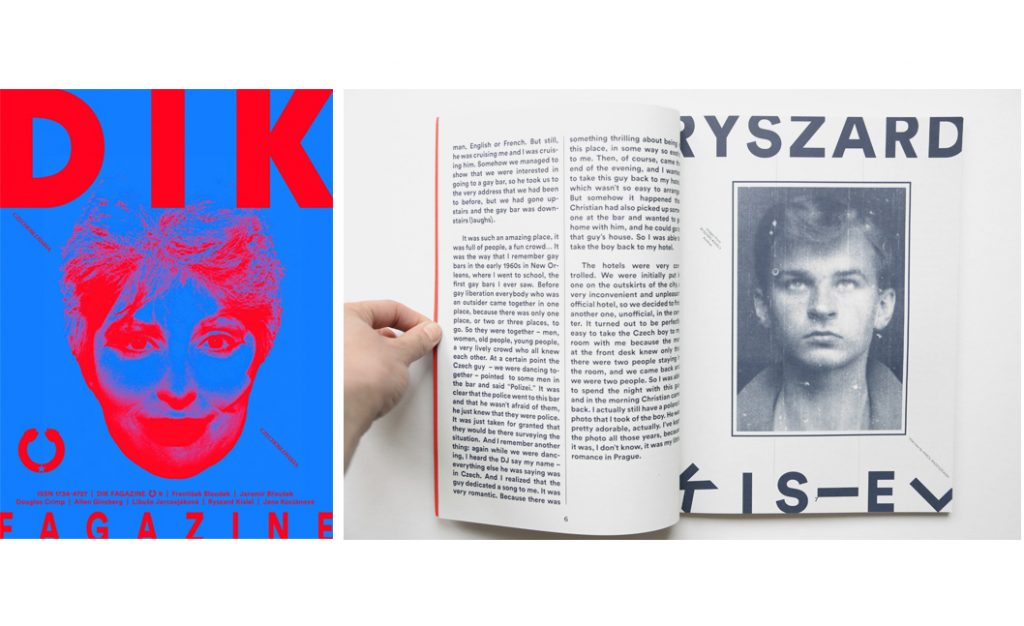

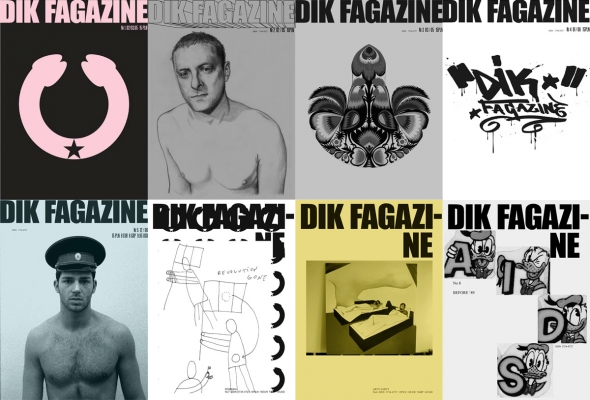

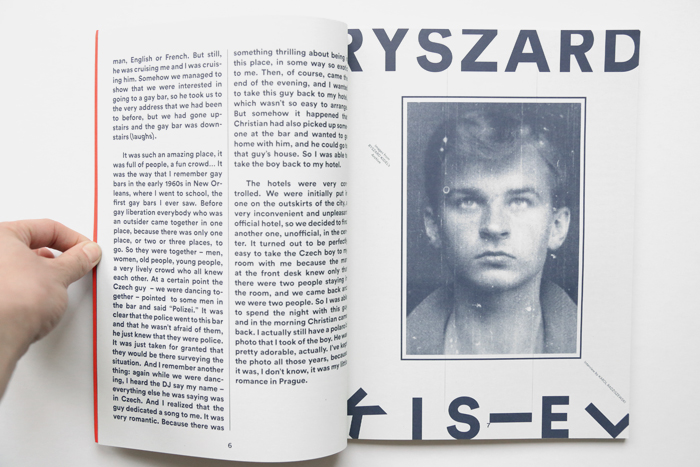

At the time of my visit, Radziszewski was preparing for a solo exhibition (currently showing) at the Ujazdowski Castle Centre for Contemporary Art. On his laptop he showed me documentation of some of the work he planned to exhibit, and we discussed his practice, particularly the serial publication (or ‘fagazine’) he has been producing since 2005, Dik. Originally a serial publication focused on contemporary queer art practices and masculinity, Dik has, over the past few years, evolved to focus more strictly on queer archives across Eastern Europe.

This necessitates a vast amount of dedicated research on his part. In a country like Poland, where gay, bi, trans, and other forms of queer identity are highly contested, such archives are generally unofficial, private, informal collections, assembled by activists and others. They are not open public resources. Where historic publications existed, they tended to be subterranean, circulated through underground networks; likewise clubs and other social centres would have operated clandestinely; questions of personal safety, privacy, discretion are key considerations. Radziszewski’s research in this field places him alongside other queer artists working internationally in this field, such as Sharon Hayes, Ted Kerr, Ulrike Müller, Padraig Robinson, Patrick Staff, Chris E. Vargas, Ed Webb-Ingal, and Emma Wolf-Haugh. In many cases, such artists find themselves generating archives, interacting with older activists, artists, and other participants in the queer subculture of previous decades. The task then is to manage this material sensitively and responsibly, given the duty both to the privacy of the individuals involved and to the wider social context, in which the visibility of these histories is of pressing importance. (Sam Lefebvre has written interestingly on the difficulties involved in archiving and digitising materials originally intended to circulate within these kinds of subterranean queer networks.).

In 2015, Radziszewski formed the Queer Archives Institute (QAI) as a formal mechanism to develop this aspect of his practice. For the tenth issue of Dik, he documented a month-long residency of the QAI at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Zagreb, where he was commissioned to queer the museum’s collection. (Kevin Brazil has recently written a thoroughgoing reflective essay on this imperative to queer art institutions. In Zagreb, Radziszewski set up a temporary office of the QAI in an unused public corridor of the gallery, operating his research in full drag and exploring queer histories he was able to uncover and recount in the publication. He has undertaken related projects elsewhere; the QAI is an ongoing initiative.

Radziszewski has set himself a formidable but important challenge, given how sexual orientation and gender identities have been strategically demonised in parts of post-communist Eastern Europe, as of course in Russia, in recent years. In these places, queerness – in particular male homosexuality – is cast as a western phenomenon, an ‘infectious’ force, threatening to move eastward. This hysterical narrative is reflected both in social attitudes and in legislative developments. The governing Law and Justice Party have blocked all moves to introduce marriage equality; homosexuality is spoken of as a ‘plague’. Across a number of Polish cities, LGBT-free zones have been declared. The government have moved to ban sex education for minors altogether. In Poland, homophobic propaganda has been grafted onto a strain of virulent patriotic nationalism.

This has engendered a new regime of official censorship. Only a few weeks before my visit, in April 2019, the National Museum in Warsaw removed works by feminist contemporary artists deemed too explicit; in particular, the removal of a film work by the major Polish avant-garde feminist artist Natalia LL, Consumer Art (1975), caused an international outcry. Ujazdowski Castle (where Radziszewski is currently showing) has been at the centre of its own controversy in recent months. In Autumn 2019, it was announced that Małgorzata Ludwisiak – who has been director since 2014, establishing a significant international reputation for the institution – was to be replaced by a government appointee, Piotr Bernatowicz, known for his far-right political views. Bernatowicz began earlier this month; Radziszewski’s is the last exhibition programmed by the previous director. The incongruity of this situation – an exhibition of radical queer art overlapping with an institution’s shift to the right – is not lost on Radziszewski, who has been prominent in protesting the appointment. It follows several such ominous personnel changes in the city in recent years. The artists and curators I met in Warsaw seemed wary, but resilient. The official institutions and museums have always been subject to government pressures, and the Polish art world has, in turn, a long history of politicised action and resistance. Still, the scale and nature of the current regime’s hostility seems different, amplified.

In the west, it is customary to view the situation in Poland as a sort of throwback, an example of a nation-state in an ‘earlier’ stage of development; this kind of account posits recent ‘progress’ in parts of the west as a sort of universal arc. Radziszewski rightly resists this idea that the ‘east’ is somehow ‘behind’ the west. In America is Not Ready for This (2011–14), he explored the record of Natalia LL’s visit to New York in 1977, where her work was considered too advanced for contemporary American art audience. Likewise, the resurgence of homophobia and prejudice is not simply a sign of some innate regional retrogression. On his laptop at BWA he showed me images of Hlas sexuální menšiny (Voice of the Sexual Minority) and Nový hlas (New Voice), early Czech magazines about homosexuality from the 1930s.

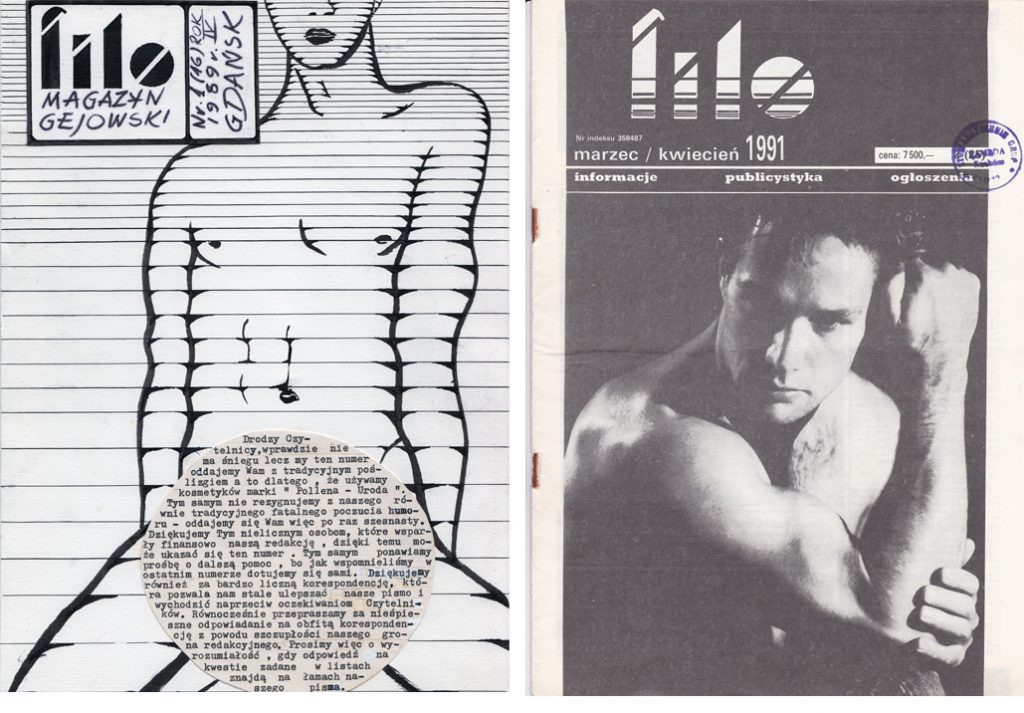

For Radziszewski it is important to explore the underground queer cultures that preceded the end of the Soviet Union, to disentangle the conflation of homosexuality with the ‘west’. This was the subject of the eighth volume of Dik, published in 2011 with the sub-header: ‘Before 89’. Through his work on this publication, he met Ryszard Kisiel, the creater of Filo, the first known queer zine in socialist-era Central Europe, and owner of a vast private archive of photos, mostly of gay men, his friends and acquaintances in the underground queer scene in 1980s Gdańsk, at a time when homosexuality was under intensive official surveillance. Kisiel’s work has been the subject of several of Radziszewski’s projects since, exploring how Gdańsk – the centre of Solidarność – was at the same time a place of progressive attitudes and relative sexual freedoms. A port city, open to the flow of ideas, as well as the flow of promiscuous bodies and desires, Gdańsk was home to a set of interlocking queer and industrial protest histories, a confluence since obscured by the ascendance to power of certain of the original dockyard protesters, many of them now members of the Law and Justice Party, instrumental in Poland’s lurch to the right.

Radziszewski’s work is a clear demonstration that these archives have resonances far beyond their function as records of the past, speaking clearly into and from the present moment. They also speak across national boundaries. Russian art critic Andrey Shental has recently written on the ways in which the ‘east’ – conventionally understood to be peripheral, lagging, ‘behind’ – might in fact be viewed as the genuine ‘avant-garde’. Witness how the superpowers in the west (Trump’s America, Brexit Britain) are adopting the xenophobic tactics and rhetoric of the ‘East’.[1] If the right is learning from these strategies of power, we should surely be paying attention to how they’ve been – are being – resisted.

[1] Andrey Shental, ‘Under Western Eyes’, Paper Visual Art Journal, Vol. 10 (Spring 2019), 11–18.

………………………………………………………………………………

Nathan O’Donnell is a writer, researcher, and one of the co-editors of an Irish journal of contemporary art criticism, Paper Visual Art. He is currently Research Fellow at IMMA in relation to the IMMA Collection: Freud Project. His writing has appeared in The Dublin Review, gorse journal, Apollo Magazine, 3: AM, minor literature[s], The Manchester Review, Southword, Architecture Ireland, and The Tangerine, amongst others, and his first book is forthcoming from Liverpool University Press. He has been awarded bursaries from the Arts Council of Ireland and Dublin City Council, as well as artist’s commissions from the Irish Museum of Modern Art, Dublin City Council, the Arts Council of Ireland, and South Dublin County Council. He lectures on contemporary art at Trinity College Dublin and on the MA Art in the Contemporary World at NCAD, Dublin.

Karol Radziszewski (b. 1980) lives and works in Warsaw (Poland) where he received his MFA from the Academy of Fine Arts in 2004. He works with film, photography, installations and creates interdisciplinary projects. His archive-based methodology, crosses multiple cultural, historical, religious, social and gender references. Since 2005 he is publisher and editor-in-chief of DIK Fagazine. Founder of the Queer Archives Institute.

His work has been presented in institutions such as the National Museum, Museum of Modern Art, Zacheta National Gallery of Art, Warsaw; Whitechapel Gallery, London; Kunsthalle Wien, Vienna; New Museum, New York; VideoBrasil, Sao Paulo; Cobra Museum, Amsterdam; Wroclaw Contemporary Museum, Museum of Contemporary Art in Krakow and Muzeum Sztuki in Lodz. He has participated in several international biennales including PERFORMA 13, New York; 7th Göteborg Biennial; 4th Prague Biennial and 15th WRO Media Art Biennale.

Categories

Up Next

Mark Granier responds to Life Above Everything

Fri Jan 17th, 2020