‘Dance of Life’ – West Tallaght Women’s Textile Collective

Artist Wendy Cowan’s work and teaching practices are firmly rooted in the processes of making and collaboration where care, labour, power, women’s and young people’s relationship to the state are made tangible through a variety of texts (film, textiles, works on paper, installations, and street happenings). Cowan now lives and works in Mparntwe-Alice Springs, central Australia on Arrernte Country and is the co-founder and co-director of Stick Mob Studio.

In this article, educator and artist Wendy Cowan diffractively reads the story and impact of ‘The Dance of Life, Shamiana Panel’ textile work made almost thirty years ago, that was brought together with women of both Irish and South Asian descent at the West Tallaght Women’s Textile Group, to explore cross-cultural understanding. ‘The Dance of Life, Shamiana Panel’ (1993) was selected by Curator Georgie Thompson for Chapter Three- Social Fabric, of the current/recent museum wide exhibition drawing from IMMA’s Collection -The Narrow Gate of the Here and Now-IMMA 30 Years of the Global Contemporary.

In her curatorial introduction Thompson says, ‘With a rich history, global reach and fundamental relationship with human existence, textiles and their production are a powerful lens through which to view some of the concerns of the last thirty years, and to read the museum’s collection and history.’ (page 136) Museum catalogue

Helen O’Donoghue, previously IMMA Senior Curator, Head of Engagement & Learning Programmes, describes the impact of bringing the panel into the IMMA exhibition space for the Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now: Social Fabric;

“I witnessed their reappraisal of their work which has been in storage and out of sight. This revisiting of the work reawakened the sense of personal and collective agency and empowerment that being involved in the process had for them. The last thirty years has seen unprecedented changes in Irish society, with changes in the demographic makeup of its population, and the role that Museums and galleries play in people’s lives. This work is one of many artworks in IMMA’s Collection that has been an outcome of our outreach policy which has been to create meaningful access to the cultural assets of this museum and is a demonstration of how art can be experienced as transformative, and museums can become significant in people’s lives. Through our programming, we have worked to build local and global connections that engage with social, political, and cultural concerns of our time.”

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Entangled exhibitions: Returning, remembering more just pasts

What I am about to talk about has gone before – here-and-now, there-and-then – which is to get a felt sense of entangled states through creative threads that trace past-present-future, intra-actions [1], across hemispheres, times, and matter/s [2]. These threads include: the textile Dance of Life created in 1993-1994 by the West Tallaght Women’s Textile Collective which was featured in the exhibition The Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now, Social Fabric (2021-2022) [3]; the launch of Stick Mob Studio’s graphic novels (2021), which threads Indigenous cultural stories and speculative fiction through every day, not-so-ordinary, desert life in central Australia; and finally the hastily written notes taken during an online talk from Karan Barad entitled ‘Re-memberings Times/s, for the Time-Being’ hosted by IMMA in 2022.

The exhibition title Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now was taken from the text Comrades of Time by Boris Groys (2009). This exhibition worked as an apparatus or weaving loom through which this paper is threaded across hemispheres, times, and matter/s. The art projects and notes work not as a succession of events, as in one follows the other, rather as the experience of pasts-presents-futures existing simultaneously. For Arrernte [4], Indigenist scholarship from central Australia and Barad’s take on quantum field theory – agential realism – time, space and matter/s are inseparable (Stuart & Georgiadis, 2015; Turner & McDonald, 2010). In my work as artist-teacher-researcher, I respect the distinctive and entangled nature of these scholarships.

The artworks and photographs in this paper are not static representations of times past, they radically remember and rethread entangled relationships. In this way they do not provide clarity to the words, nor do they represent static moments stored on film, paper, or cloth as antiquated matter/s.

Art – weaving/drawing acts of resistance

The Social Fabric exhibition guide notes, ‘This chapter considers themes of globalisation, technology, labour, community and agency through artworks that engage with textile as commodity, material and craft. These ideas form pathways across the exhibition, from feminist work to heirlooms, woven acts of resistance’. The Dance of Life textile work was created in 1993 by women living and/or working in Jobstown [4], West Tallaght, Dublin. I retell their tale with permission from the women who create far-reaching, intra-connected ‘act[s] of resistance’.

Priest with a missive [5]

In 1992, I worked one morning a week as a teacher in a women’s centre in Jobstown that was affiliated to the Catholic church. During the recruitment process the centre’s manager outlined the importance of ‘getting women out of their suburban homes so that they can participate in social learning activities that build confidence along with their personal and families well-being. Considering this, the plan was to start with watercolours and then to see what happens next. As we painted landscapes from postcards, we shared stories of what was going on in our lives. Several months later these stories materialised into an art installation, shown at the centre’s end of year community open day. The installation consisted of life-size figurative models that told stories of how it felt to live in this ‘new town’ on the edges of Dublin. During this event, I sensed that the installation took up too much space, was too controversial, and that too much interest was given to it by family and community visitors. Nothing was said until a few days later when the manager went to great lengths to pick me up to attend the staff Christmas party. In the car we talked about the open day while avoiding any mention of the installation. She told me that the women were becoming demanding, wanting a say in the type of knitting wool purchased, the choice of recipes for the cooking class. She told me, as she pulled into the venue, that I was to ‘treat the women as children’. Shocked, I fumbled a response along the lines that several women were grandmothers, all were mothers, all of whom I treated with respect.

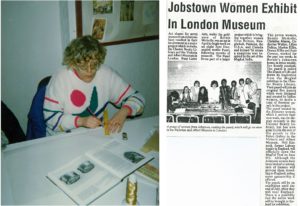

In the New Year we were invited by the Victoria & Albert Museum’s (V&A) Head of Adult and Community Education to create a textile as part of the Shamiana: Moghul Tent Project [6]. The brief was to draw from our experiences of home and displacement. Between 1994-2001, the Dance of Life textile, which made up one of over sixty Shamiana panels, was exhibited as part of a ceremonial tent in galleries across Europe, South Asia, America, and the Middle East. In the exhibition catalogue the V&A’s exhibition curator, Shireen Akbar states ‘the panels depict narrative scenes relating to home, refuge and dispossession’ .

As suburbs across Tallaght were being built, medical professionals from South Asia were beginning to arrive to provide essential services. During our weekly sessions, as we talked about our personal everyday lives within wider political and social issues, we put out an invitation through the local health centre for South Asian women to join for a visit to Chester Beatty Library and the National Museum of Ireland to meet curators and to sketch the Moghul Collection of miniature paintings and early Irish artefacts. A week later, the manager arrived unexpectedly to inform me that my role was no longer required. The conversation ended when there was a knock on the door – I was called back to the art room. The manager drove off, leaving us in deep conversation. I heard stories about how the manager was becoming agitated when the women requested to be involved in the running of the centre. As I rode my bike back across Dublin, I thought about the initial conversation when I was told that the centre was established to ‘get women out of their suburban homes so that they could participate in social learning activities that build confidence as well as their personal and families well-being’.

What to do? I was shaken and vulnerable. Working as an artist I needed the money; it was winter in an economically depressed country and the project could fold under the weight of the manager’s anxiety. I called a meeting to ask for an explanation and hopefully to negotiate a way forward. At the end of the following art session a Jobstown parish priest arrived handing me a white envelope. He could barely make eye contact. I read the letter out loud. My contract had ended. Unanimously and automatically, we packed up and moved to Bernie’s kitchen three doors down. To cover basic materials, we applied for funding from the Tallaght County Council. Our existence – a collective of creative women separate from church and state institutions – was treated with suspicion as we were going ‘against the grain’ of social life.

Bernie’s kitchen became our home and refuge: where we drank cups of tea, kept an eye on the children, talked about our fears and strengths – usually with raucous humour. In a crowded domestic space we threaded, stitched, and patterned our thoughts, stories, and relationships into the fabric.

We captured our personal stories of strength and vulnerability in miniature paintings that surrounded the central panel where an Irish and Indian woman are dancing, inspired by Moghul paintings and Celtic manuscript illustrations. The textile was manifesting a fledging shift in Irish identity from monocultural to pluralistic – through telling and materialising stories that didn’t fit to the repetitive norms of what it means to be Irish.

Image 2: June O’Connor, Wendy Cowan, Lilian Dalton, Catherine Walker, Christine Mason, Promilla Shaw, Jilloo Rajan, Marion Kilbey, Bernie McCarville.

This is significant because while we were stitching and embroidering a textile that tell stories of women’s prophetic intelligences, a mother, an academic, a barrister and member of the Seanad Éireann, Mary Robinson was elected as President of Ireland. In her Inaugural Speech in Dublin Castle, she pledged:

“As President I will seek to the best of my abilities to promote this growing sense of local participatory democracy, this emerging movement of self–development and self-expression which is surfacing more and more at a grassroots level. This is the face of modern Ireland” (Robinson, 1990).

I met President Mary Robinson at several exhibitions where she mapped points of political and social connections through artwork that would otherwise remain dormant, unrealised, and avoided. I cried often when Mary Robinson spoke, her words resonated with ‘stepping out’ of the women’s centre where our voices and actions, in their fragility, were dangerous. The words of the Irish poet Eavan Boland continues to ring in my ears and my heart, ‘[o]nly when the danger was plain in the music could you know their true measure of rejoicing in finding a voice where they found a vision’ (1994, p. 3).

As we stitched, we talked about our messy feelings around the loss of project funding, lack of wool for knitting projects (it was winter) our growing disbelief in ideologies wrapped up in phrases such as ‘for your own good’ and ‘in your best interests’. Refuting these ideologies meant that the textile work and the women’s collective became the problem to be expelled, not the set of behaviours and structures within the church that upheld the ideology.

Walking out of the women’s centre into Bernie’s kitchen on a cold skull grey February morning, sharp winds off the Dublin mountains dislodged calcified, risk-averse ideologies, it felt safer to be vandalized by art and wind, to be rendered in/determinate and dangerous. The icy wind hitting our backs as we sought refuge was surely haunted. Hauntings that trouble the divide between absence/presence, not merely in the sense of holding memories of the dead nor the lingering of violent passing events (Barad, 2022). These hauntings – us, a group of women seeking refuge, the textile in it’s making – ‘are the eliminable materials of existing conditions’ (Barad, 2022).

In Bernie’s kitchen, we in/directly asked ourselves if the cost was too high, did we have the resolve, the courage, the skill to resist the threat of annihilation through our blatant audacity to challenge acts of cruel retribution (priest with a letter, a missive ushered to ensure compliance).

The Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now, Social Fabric

Image 2: Narrow Gate of Here and Now: Social Fabric, 2022, ‘Dance of Life’ exhibition label

The Dance of Life was acquired by IMMA in 1993 and first exhibited in 2000 as part of the Shamiana Mughal Tent, after an international tour organised by the V&A. It was exhibited again from 2021-2022 in the exhibition The Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now. In returning, reconnecting, remembering through the present as ‘existing conditions’, these matters/moments in their entanglement bring an embodied material sense of the here-now: not as a succession of moments but as materially co-existing, a superposition of times in this thick now (Barad, 2017, 2022).

The Dance of Life isn’t about going back to past times, but rather the material re(con)figuring of space time mattering so as to hold account the subjection wrought by the church and state over women’s bodies while manifesting and exhibiting different possible, more ‘just’ histories for ‘stepping out’.

Stick Mob Studio storytellers, central Australia and Northern Territory

Published in partnership with the Indigenous Literacy Foundation, Gestalt Publishing and Pan Macmillan. 1, Mixed Feelings – written, illustrated and coloured by Declan Miller. 2, Exo-Dimensions – written and illustrated by Seraphina Newberry and coloured by Justin Randall. 3, Storm Warning – written by Lauren Boyle, illustrated by Alyssa Mason.

In Australia – while the Dance of Life was exhibited at IMMA in 2021, Stick Mob Studio, a collective of Arrernte storytellers launch their graphic novels to a packed venue in Mparntwe – Alice Springs. In a different time-zone, surrounded by desert matters, Stick Mob authors and illustrators disrupt the sedimenting logics of colonial linear time as they jump time. In their speculative stories, Arrernte Country, remorphs and reimagines past-futures where Indigenous young people are not required to catch-up on colonial progressive time, serve time, or do time, which resets the colonial project to roll out successive interventions (Mellor & Corrigan, 2004), such as the Northern Territory National Emergency Response [7].

When Stick Mob and I publish creative work we are troubling institutional education systems where Indigenous young people are positioned as problems to be fixed. Stick Mob’s graphic novels, along with this paper and the Dance of Life textile, testify that it is possible to move through the narrow gate of the here-and now – to pull, stitch and cut different threads in social fabrics to make spaces for radical political creative imaginaries where difference is made possible rather than its destruction (Barad, 2022).

At the end, I return to the Narrow Gate, to a thick now – to listen with cloth touched by women and children, institutions and exhibitions, to the wind blowing off the Dublin mountains, to the sound of more just histories told through touchy threaded matter/s.

Footnotes

[1] In Barad’s words, ‘The usual notion of interaction assumes that there are individual independently existing entities or agents that preexist their acting upon one another. By contrast, the notion of ‘intra-action’ disrupts the familiar sense of causality (where one or more causal agents precede and produce an effect), and more generally unsettles the metaphysics of individualism (the belief that there are individually constituted agents or entities, as well as times and places)’(Juelskjær & Schwennesen, 2012).

[2] The slash in matter/s indicates that matter, as a verb (matters of care and concern) is inseparable to matter as a noun (art, wind, threads). This inseparability comes from Arrernte Indigenist theories of rationality (Stuart & Georgiadis, 2015; Turner & McDonald, 2010) and Barad’s quantum theory ‘agential realism’ (2007). In this instance matter/s include – art, home, refuge, dispossession, resilience, friendship, and storytelling.

[3] Social Fabric is the third chapter of a four-chapter exhibition at IMMA, The Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now, a museum wide exhibition serving to celebrate IMMA’s thirtieth birthday by showcasing works from their collection and to reference IMMA’s role in Irish society since 1991 (Thompson, 2022).

[4] I acknowledge Arrernte Country, central Australia where I write this paper and the country where I was born, Ireland. I pay my respects to elders who assist me in the work I do, which is embodied in relationality and justice. This paper is not easy to write, nor to reread – there are many hauntings to grapple with.

[5] Arrernte Country is in the centre of Australia. Eastern and Central Arrernte and Western Arrarnta peoples live in this region which ‘holds very important ancestral journeys that have travelled in and around the Central Australian landscape in many forms from when time began’ (Riley).

[6] In 1992, Jobstown was one of many newly built housing estates on the far edges of Dublin consisting of a web of narrow roads, lined by identical working-class two-story houses. These ‘newly built’ and ‘monotonous’ housing estates were built to accommodate families moving from their homes in the ‘older’ suburbs located closer to the inner city (MacLaran & Punch, 2004, p. 37). Code words for inner city gentrification.

[7] The missive enacted the control of the catholic church in Ireland – from Pope John Paul’s visit in 1979 to the unmarked graves of over a hundred ‘fallen women’ (unmarried mothers) instutionalised in the Magdalene Laundries (Asylums) run by the catholic church throughout the 18th, 19th, and 20th centuries (300 years of slavery of over 30,000 women). See the documentary – ‘Sex in a Cold Climate’ (Humphries, 1998) and Caelainn Hogan’s book Republic of shame: stories from Ireland’s institutions for ‘fallen women’ (2019). The Magdalene Laundries was located on Sean McDermott Street, South Dublin, which is named after Seán Mac Diarmada, an executed (by the British for high treason) Irish Republican leader of the 1916 Easter Rising. This military uprising is mentioned in the Preface. I worked on an arts project in a women’s centre on Sean McDermott Street in the 1990’s, without knowing that a few doors down women were held captive to a moral problem that the church and state created and imprinted on female bodies.

[8] The Northern Territory National Emergency Response, also known as ‘The Intervention’, was a package of measures enforced by legislation affecting Indigenous Australians in the Northern Territory of Australia, which lasted from 2007 until 2012. The measures were numerous and included restrictions on the delivery and management of education, employment, and health services in the Territory. The measures proved controversial, being criticised by the Northern Territory Labor government, the Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission and several Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander leaders. The Act was amended by successive Federal governments, finally repealed in July 2012 by the Gillard government, which later replaced it with the Stronger Futures in the Northern Territory Act 2012

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2022). Corrective Services, Australia. ABS.

Akbar, S. (1999). Shamiana: The Mughal Tent. London: Victoria & Albert Museum.

Barad, K. (2022). Re-memberings Times/s, for the Time-Being. Paper presented at the IMMA Talks Online

Beard, A. (2013). Mary Robinson: Leadership. Harvard Business Review, online. Retrieved from tps://hbr.org/2013/03/mary-robinson

Boland, E. (1994). In a Time of Violence. New York: Norton.

Cowan, W. (2000). A tent of ideas, visions and actions. In Shamiana: Mughal Textiles 2000-2001. Dublin: IMMA.

Groys, B. (2009). Comrades of Time. e-flux Journal, (#11).

Hogan, C. (2019). Republic of Shame: Stories from Ireland’s Institutions for “Fallen Women”. London: Penguin.

Humphries, S. (Director). (1998). Sex in a Cold Climate. Dublin, Ireland: Testimony Films.

MacLaran, A., & Punch, M. (2004). Tallaght: The Planning and Development of an Irish New Town. Dublin.

Robinson, M. (1990). Inaugural Speech given by Her Excellency Mary Robinson, President of Ireland. Paper presented at the Stanford Presidential Lectures in the Humanities and Arts. Robinson, M. (2013). Mary Robinson: Everybody Matters – A Memoir. St Ives: Hodder & Stoughton.

Thompson, G. (2021). Curator’s Talk Series: The Narrow Gate of the Here-and-Now, Social Fabric. IMMA.

Categories

Up Next

IMMAxDean Artist Spotlight with Thaís Muniz

Sun Dec 11th, 2022