Patrick Hennessy and the power of artworks

In the most recent installment of our Curator’s Voice series, IMMA Curator Seán Kissane observes how his own relationship with artworks in the exhibition Patrick Hennessy De Profundis has changed over the course of the show and how conversations with visitors, peers and friends has resulted in some powerful and compelling responses to the emotional subject matter of the paintings.

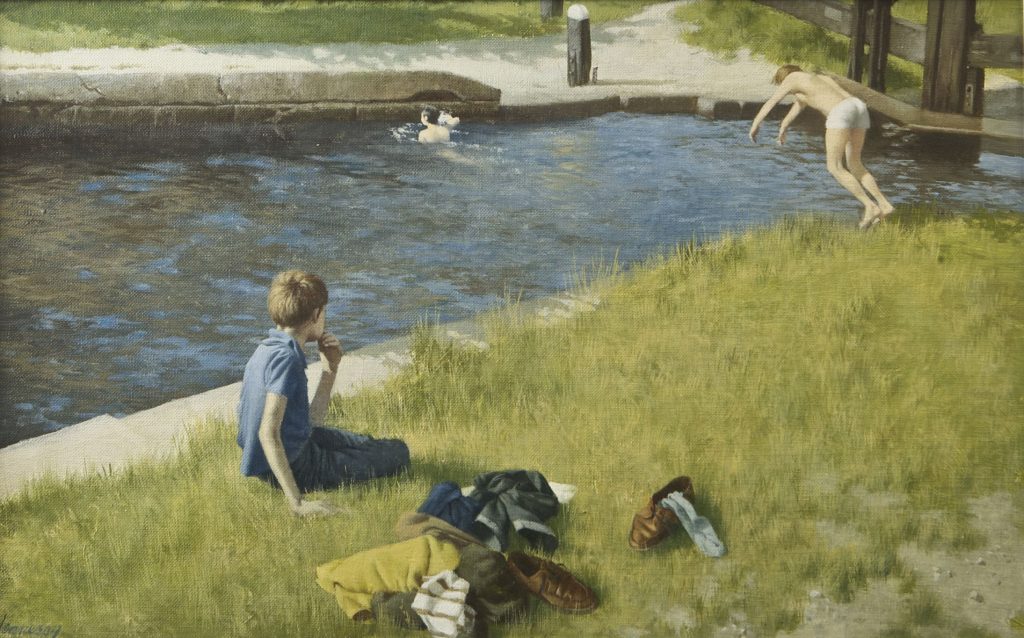

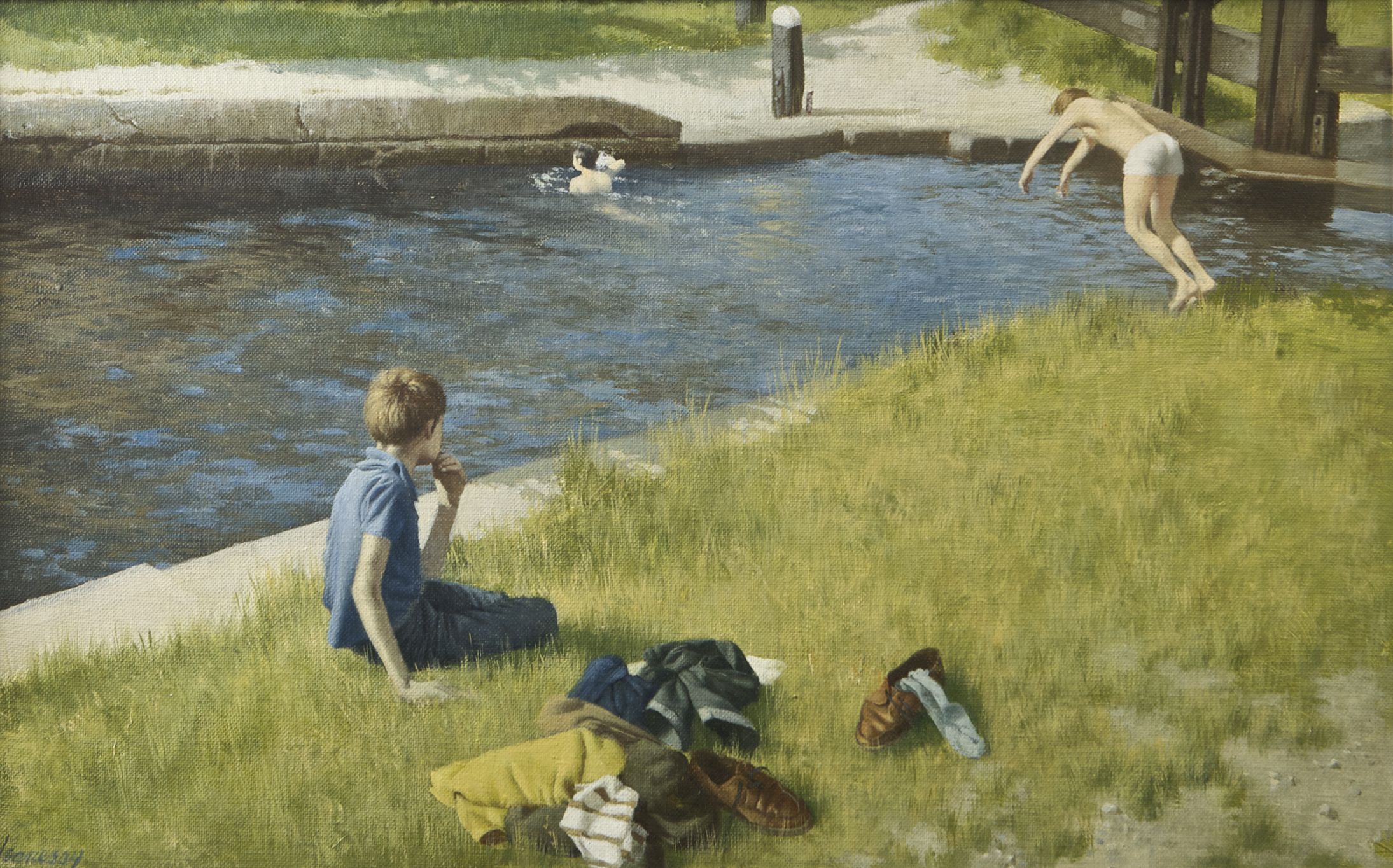

One of the most rewarding aspects of curating an exhibition is observing the ways in which one’s relationship with individual works changes over the course of the show. The conversations one has with visitors, peers and friends constantly challenge and enrich the interpretations that may have been formed in the course of research. The Patrick Hennessy show has been no exception. As it deals with emotional subject matters like sexual orientation, psychological alienation and coming out; some of the responses I’ve heard have been powerful and compelling. One quiet little work in particular has provoked much discussion. By co-incidence it is entitled Seán Alone and Hennessy painted it shortly before he died. It shows an adolescent boy sitting by the side of a canal, looking after a pile of clothes as his friends swim boisterously in the water. I had always seen this image as representing psychological isolation, although he is surrounded by his peers, the title tells us that the protagonist is alone. I imagined Seán’s thought processes, his awareness of his difference and how the weight of that gradually increased over time to that point at which it became unbearable and his journey of coming-out would begin.

During the exhibition other gay men have read the work in more physical and literal ways. They focused on the fact that Seán remains fully-clothed as his friends went swimming. One man said this resonated with him, because as a teenager he didn’t like to take off his clothes. He was attracted to one of his close friends and was ashamed that he couldn’t control the unwelcome responses of his body – added to this his ‘response’ might have had negative consequences. Another man described how as a teenager he was very thin. He didn’t like to show his body because he thought that somehow his ‘weak’ body betrayed him, that his other ‘weakness’ would be revealed. At our recent seminar, Sexuality, Identity and the State some of these ideas were teased out by a number of psychoanalysts who responded to Hennessy’s images. As a reflection of their professional practice, they looked for emotional insights in the faces of his sitters, and in particular their eyes. The analysts saw various things, from pain through to suppressed anger in his portraits. Seán Alone was singled out as although he has his back to the viewer, there is still a palpable sense of exclusion and alienation to be discerned in the way he holds his body.

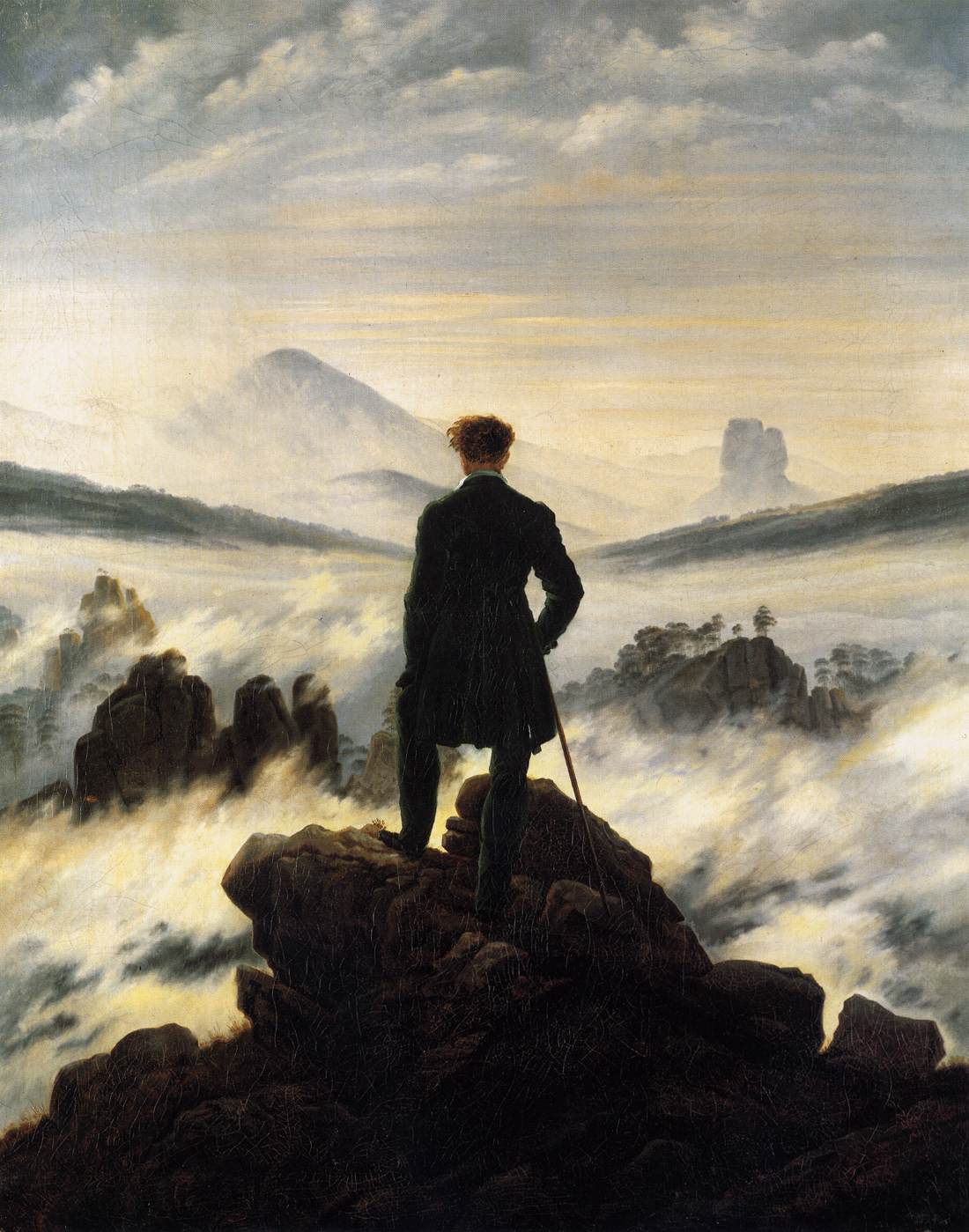

Seeing a figure from behind comes from the German sublime tradition of the Rückenfigur, most familiar from Caspar David Friedrich’s Wanderer above the Sea of Fog (1818). Friedrich was the prime exponent of the German Romantic Style, the foundations of which were laid by Jean-Jacques Rousseau. Essentially a reaction against the pure rationalism of the Enlightenment, they created a philosophy that integrated emotion and sensuality with an awareness of God and his creation. Rousseau argued that ethics emerged from the emotions – not reason or morals. His famous quote ‘Man is born free, but is everywhere in chains’, expresses the idea that man is inherently good and compassionate, but corrupted by society.

Hennessy’s use of this Romantic convention points in two directions. All men are good, all are created in God’s image, and the private beliefs of a citizen do not preclude them from participation in society. The use of the Rückenfigur as a device has the function of activating the viewer; we see the world through the protagonist’s perspective and we empathise with his experience. In many ways Hennessy was ahead of his time. Before the contemporary language around ‘coming out of the closet’ was in general use, he was perceptive and sensitive to the nuances of self-awareness and his characters are shown undergoing a gradual development. He depicts men at different ages in their lives from adolescence to maturity; they are also shown at different stages of their personal development from fear through to acceptance. In a country where young gay men grew up without any visible role-models, Hennessy’s Seán Alone is one of his works that attempted to visualise their lives and emotions for the first time.

The exhibition Patrick Hennessy De Profundis, curated by Seán Kissane, is now in its final two weeks ending on Sunday 24 July. Part of the IMMA Modern Irish Masters series you can access a wealth of information about the artist on our mini site.

Join Seán Kissane for an insightful walk through of the exhibition on Saturday 23 July at 1.15pm. No booking required, meet at main reception. Free. Arrive early to avoid disappointment as numbers are limited.

Categories

Up Next

Memorial Gardens

Tue Jul 5th, 2016