Sam Jury on 'All Things Being Equal'

The exhibition of Sam Jury’s film work All Things Being Equal in the IMMA Project Spaces coincides with a talk by Derval Tubridy entitled The unthought and the harrowing: Samuel Beckett’s Necessary Art. Johanne Mullan, National Programmer at IMMA, spoke with Sam Jury about how the work of Samuel Beckett has influenced her practice.

All Things Being Equal was edited and completed during your residency at IMMA in 2009/2010 and is now part of the IMMA Collection. Did the time spent in Ireland influence the direction of the work?

When I went to IMMA, I’d just started making moving image works. In fact, that’s why I wanted to do a residency, because I needed time to explore this shift in practice, which was naturally also an ideological shift. Structurally I was thinking about these first video works as simply ‘non linear’ or ‘non narrative’, which is not exactly right – it’s probably more accurate to call them circular, because they all ran continuously without seams or punctuation – a repetition of acts. I initially picked the IMMA residency because the emphasis is more on process (rather than completed work or projects). Alongside this (although I say it more in hindsight), there is something about Irish culture, specifically as it relates to literature, that was both a draw and a slow-burn influence. I believe it was this, along with the open-ended approach to ideas and creativity at IMMA, that had an impact on the direction of my work.

You reference Samuel Beckett in your work, how early in your practice did this interest develop?

It’s hard to pinpoint when/where the Beckett reference began. Maybe it’s too obvious to claim a kind of synergy. But up until about 6 years ago, I hadn’t read or seen a huge amount of Beckett –more than a lot of people perhaps, but I can’t say he was a conscious influence. These last few years, working with choreographer Luca Veggetti and composer Paolo Aralla, on the film For Lengths, which is much more specifically related to Beckett (in this case the stage directions and sketches), I am much more immersed – so it’s hard to remember how things overlapped. What I can say with confidence is that whenever I experience Beckett, I understand a little more about what it means to exist. Many people seem to find Beckett’s work dark, or joyless, often obscure, but I find his work full of life – extremely real and honest, and often with great humour – albeit a kind of tragic one. There’s something about the physicality of the words, when performed (even in one’s head) that moves the work beyond representation into something more visceral and essential. For instance, Not I (by Neil Jordan, IMMA Collection) conveys no obvious narrative sense, and yet the meaning is so present, so emotive. For me, this is really interesting to think about in terms of abstract languages – how to convey existence, through all the details and seeming white noise, of being human – without ‘representing’ it.

These ideas, I think, are something I have long been interested in exploring through my work, but they only really started to make sense as time-based practice. One of my first videos of this nature was Over for the Day, a short looped work depicting the endless repetition of a tragi-comic figure blowing around in an oppressive landscape. At the time, I was exploring an oblique, performative, approach to life’s rituals – the things we cleave to as a way of making us believe we have some control, when we are generally in the throes of a much larger force. Beckett was a kind of tangential reference here – like Act Without Words – where there is some force off-stage controlling the central figure. How we act in the face of things we cannot control is central to humanity. So there is definitely something about moving image’s ability to convey repetition and how this can serve as a way to focus on and/or scrutinise the detail, that I am responding to. Of course, this is a recurring element in Beckett, but also in life – repetition, ritual, frustrated acts… and the poetry of it all.

The positioning of the camera and framing of the image, echoes a similar working practice to Beckett. Is this deliberate or coincidental? I am also interested to hear about the exploration of the intrusive camera in your work.

I do tend to frame my work to deny specific context – to remove the ‘clutter’ that can mediate the reading – and so make time and place unknown. To me, this does correlate with a kind of Beckett vision, but it’s not a deliberate reference – I have always had a fairly ‘pared back’ aesthetic.

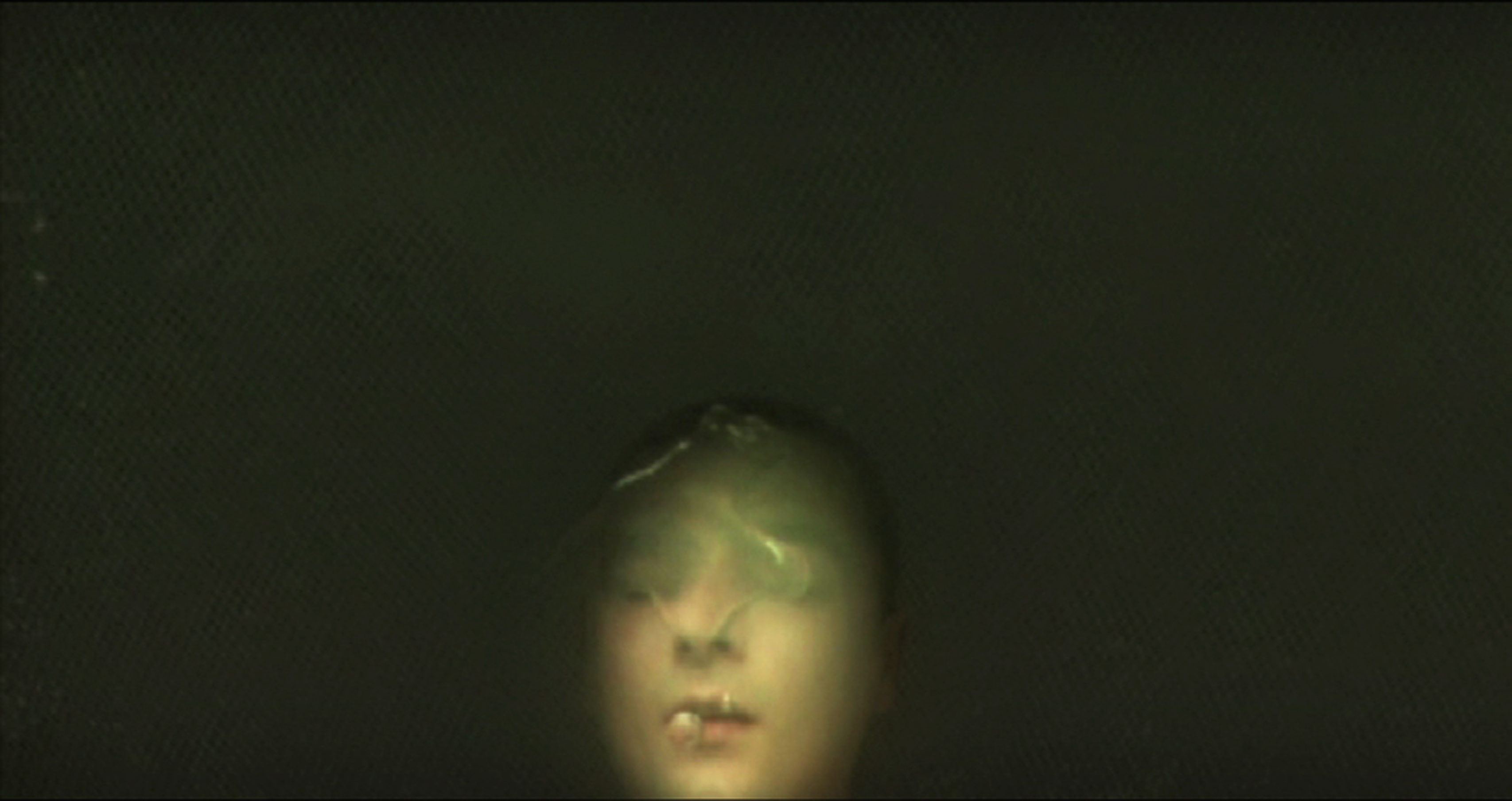

The intrusive camera is another such vehicle for this ‘denial of context’ because of its relenting fixation on the subject. This is definitely part of much of my work, including All Things Being Equal. It combines both the frustrated act (less overt – but there is a sense of purpose unknowable) and the symbolic plaguing of a material force (the water) which is neither part of nor separate to the figure. The camera is the fixed ‘intrusive’ eye, something I continued to explore whilst in Dublin, specifically with works like About Nowhere and So Let It Go. When thinking about this body of work, I’m often pulled back to Beckett’s comment on his work Film where he talks about the flight from ‘perceivedness’. I think this is so resonant for the age we live in now, where there is no escape from the camera or the screen that reflects us. The use of mass media and digital technologies, specifically its role in shaping perceptions of the self and society, is something I have been interested in for many years.

Could you discuss the parallels, if any, to trauma and repetitive memory?

Yes, I think this follows on from this idea of ‘escaping’ the reflection and the ever morphing role of the viewer/maker/camera as omnipotent author of perception and memory. I think this is one of the developments from my residency at IMMA. An on-going examination of what I have been terming ‘suspended trauma’ – an exploration of our tendency to revisit traumatic or dramatic events of our past and how this is perpetuated, distorted, made unrelenting by the camera and screen technologies. These records, these events are omnipresent, yet always set adrift from the original moment and place. Visually, and perhaps viscerally, we keep reliving them through the repetition. The suspension is created through this denial of conclusion, because these events simply restart all over again.

Derval Tubridy’s talk entitled The unthought and the harrowing: Samuel Beckett’s Necessary Art will take place on Wednesday 12 August 2015, 1 – 2pm, Johnston Suite, IMMA, in collaboration with the Samuel Beckett Summer School, TCD. Visit the event page for further information and took book a seat.

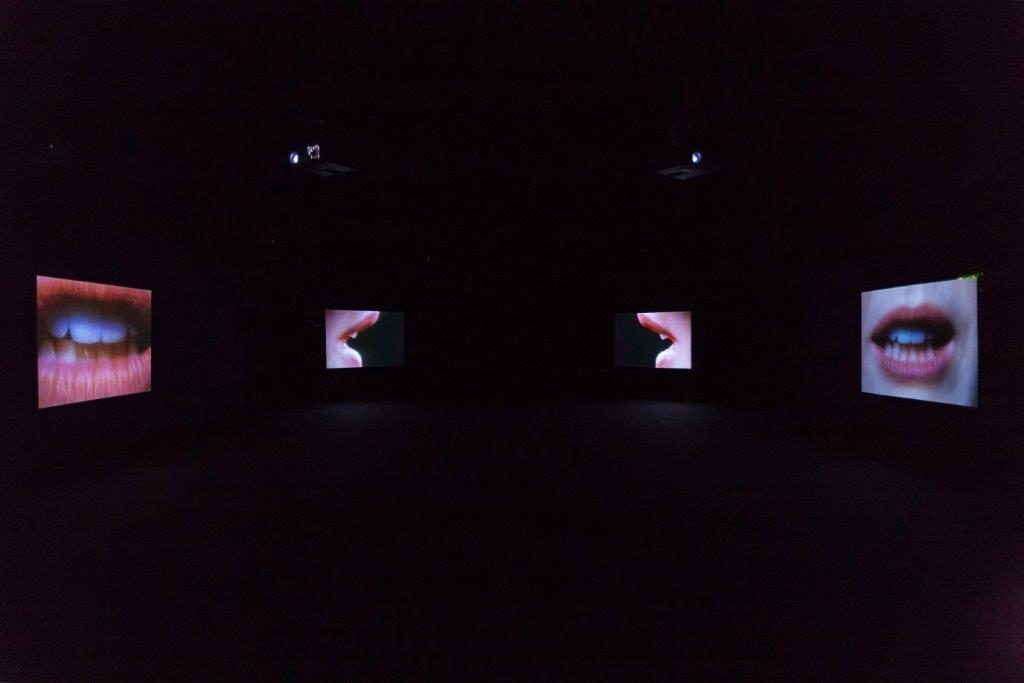

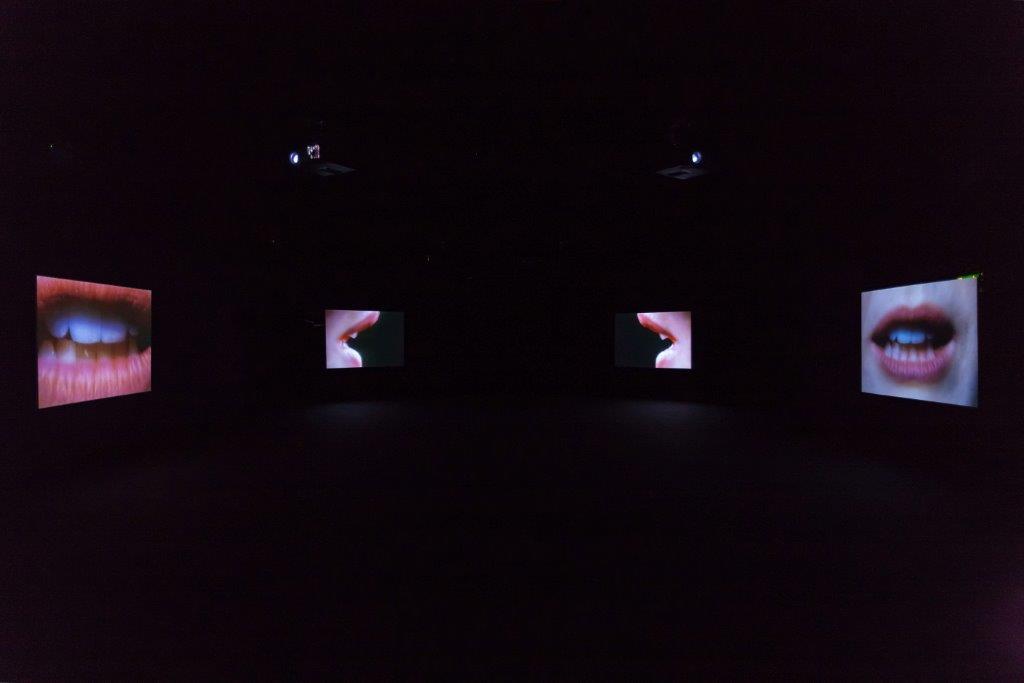

Image credits: Sam Jury, All Things Being Equal, 2009, Single channel digital (silent), Continuous loop – 11:58 before repeat, 152 – 243 cm, Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, Donation 2010. Link to work in IMMA Collection

Neil Jordan, Not I, 2000, an adaptation for film of the play Not I, 1972 by Samuel Beckett, 2000, Directed by Neil Jordan, produced by Blue Angel Films. 6 screen installation with sound, Collection Irish Museum of Modern Art, Gift, the artist, 2000. Link to work in IMMA Collection

Sam Jury in her studio during her time on the IMMA Artist Residency Programme.

Categories

Up Next

El Lissitzky: The Artist and the State

Thu Jul 23rd, 2015