Monir’s Garden

This work is currently on show in Sunset, Sunrise, a major exhibition of Farmanfarmaian’s work at IMMA. The exhibition closes on Sunday 25 November 2018.

Monir’s Garden

A Book of Verses underneath the Bough,

A Jug of Wine, a Loaf of Bread—and Thou

Beside me singing in the Wilderness—

And Wilderness is Paradise enow.

Lost in Translation

Persia. The old name for Iran is beautiful, exotic, other; as seen through my Western eyes. But Western eyes can miss the subtleties of another culture. Take, for instance, the above lines of poetry from Edward Fitzgerald’s “transcreation”, the Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám, the 1859 translation from Farsi to English of a selection of quatrains attributed to the Persian poet Omar Khayyam (1048-1131). Fitzgerald confessed to taking liberties with the original quatrains, but claimed he was faithful to the spirit of the verses. (In his own lifetime, Khayyám came under severe criticism from the Persian authorities for his unorthodox philosophy). The controversies surrounding the translation, and the authorship of the quatrains, emphasises the differences between English speaking and Iranian cultures.

Sacred Geometry

The Iranian artist, Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, born in 1924, successfully blends the aesthetics of east and west. Like Omar Khayyám, Farmanfarmaian is fascinated by the infinite possibilities of geometric forms. During his lifetime, Khayyám was best known in his native Persia as a distinguished mathematician and astronomer.

Farmanfarmaian is renowned for her works of reverse glass painting and mirror mosaics, inspired by the geometry and the architecture of ancient Iran blended with western Modernism – “All my inspiration comes from Iran – it has always been my first love.”

Exile

How tragic it must have been for the artist, then, when she and her husband, Abolbashar Farmanfarmaian, went into exile in New York in 1979, the year of the Islamic Revolution.

Shazdeh’s Garden

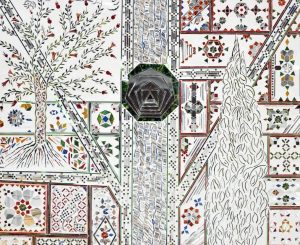

Farmanfarmaian returned to live in Tehran, in 2004. Shazdeh’s Garden, 2010, which is made with little shards of mirror, and glass painted on the reverse, is figurative, and close to the folk-art of Iran, the coffee-house paintings that Farmanfarmaian admired and collected for many years.

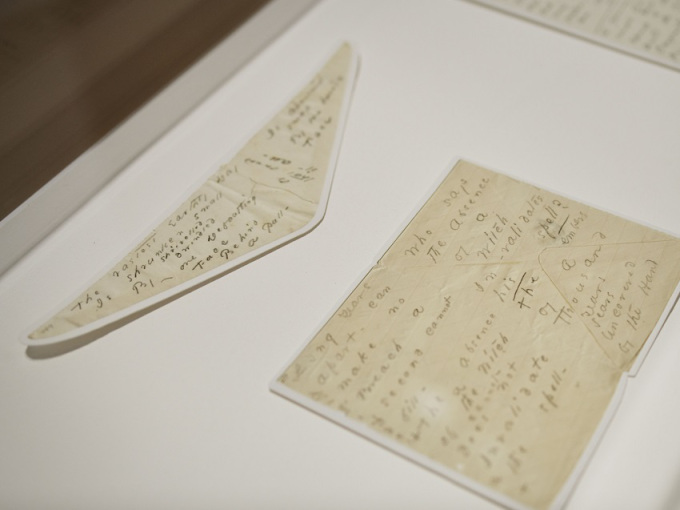

The garden is of utmost importance in Iranian culture. Throughout her life, whether in Tehran or New York, Farmanfarmaian has tended her gardens, drawn flowers and birds, and famously enlisted the help of bees to make some of her drawings.

Persian Paradise

Shazdeh’s Garden evokes aspects of Iranian life and history, from architecture to Zoroastrianism. Even the word paradise comes from the old Farsi word Paridaida, meaning “walled enclosure”. The walls of a Persian garden provide shelter from the sun, and privacy.

Reflecting the Divine

The inspiration for Shazdeh’s Garden may have been Shazadeh’s Garden, in Shiraz, in southern Iran, which is an oasis surrounded by desert. In Iranian culture, the soul is a mirror that reflects the divine, and water shares this quality of reflection. In Shazadeh’s Garden, water runs over steps to form a waterfall, creating a stunning, central set piece as you walk through the arched entrance.

Pomegranate

The pomegranate tree is grown all over Iran for its decorativeness as much as for its fruit. Farmanfarmaian places one here, in the top left corner, in bloom and in fruit simultaneously. The pomegranate features in myths across the world, symbolising fertility and abundance, amongst other things. Poor Persephone, the Greek Goddess, was pulled back to the underworld for six months of every year; one month for every illicit pomegranate seed she had eaten there.

Myth and memory

The late, great A.A. Gill, described his first pomegranate as “a treasure box of beautifully packed precious beads…” He later understood that its sweet and sour taste was an allegory for his homesickness, and for his first kiss, aged twelve, at boarding school.

I ate some pomegranate seeds today; ripe, rich red garnets, and thought of Persphone’s loneliness, stuck in her own, dark, “Groundhog Day”. And of Farmanfarmaian, in exile in New York from 1979 until 2004. I thought of Monir’s generous, resilient and dignified attitude to life, love, art, exile, friendship, heartache and home.

Visit the exhibition Sunset, Sunrise by Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian, before Sunday 25 November 2018.

Categories

Up Next

Daphne Wright, Freud and the poems of Emily Dickinson

Tue Nov 13th, 2018